Double Suicide, 1969, directed by Masahiro Shinoda, written by Masahiro Shinoda, Tôru Takemitsu, and Taeko Tomioka, from the play by Monzaemon Chikamatsu.

It's a truism that film has its roots in theater. Less remarked upon is how shallow those roots usually are: most movies owe more to melodrama and vaudeville than to Shakespeare. And they owe twentieth century drama almost nothing. Okay, there are a few exceptions: the highest of the highbrows might lift from Strindberg, Hollywood occasionally produces schlock Pirandello and very occasionally Pirandello. But tell me, which filmmakers take their cues from Beckett? Who are Ionesco's cinematic heirs? And when's the last time you heard a movie described as Brechtian? If you want to find a school of theater that's had less influence on film than the modernists, you'd have to go back to the truly obscure and neglected. Like, say, Japanese Bunraku puppet plays of the 18th century. But every rule has its exceptions, so allow me to introduce you to the film with the most statistically improbable dramatic heritage of all time: Double Suicide, the one and only Brechtian adaptation of an 18th century Bunraku puppet play.

It's a bold move to try to create Brecht's verfremdungseffekt in film, the most seductive of all media. Shinoda manages it in several ways, starting with the title, which pretty much dissolves any doubt about the film's outcome. It's right up there with M. Night Shyamalan's Ghost of a Dead Psychologist. If that effekt isn't verfremdungs enough for you, Shinoda begins his film backstage at a Bunraku production of Double Suicide. Puppeteers gear up in black robes and hoods while a man who I assume to be Shinoda talks on the phone to "Miss Tomioka," presumably screenwriter Taeko Tomioka. "The lovers' suicide journey will be through a graveyard," he tells her. "I think it's stale," she replies.

When the actual story begins, Shinoda constantly reminds the audience that they're watching a theatrical story with a predetermined outcome. The first time we see beleaguered merchant Jihei, he is crossing a bridge. We see four neat, geometrically composed shots of Jihei walking (none of which contain anything to puncture the illusion that we are observing a real person). Then in the fifth shot, the camera pans down from Jihei looking over the bridge to the rocks below. There, surrounded by puppeteers, the camera finds the bodies of Jihei and his lover.

That bridge is one of the only realistic looking locations in the film. Shinoda's interiors are abstract and theatrical to the point of absurdity. Instead of walls or floors, he uses giant replications of period engravings, like some kind of pop art installation.

Again and again, the audience is forcibly discouraged from identifying with the action on screen, from forgetting they're watching a movie. This is Jihei's home:

You can see in that shot that Shinoda is going to have a problem here: the composition and lighting are too good. It's just as easy to coast along on the images as it is to lose yourself in the onscreen narrative, and that doesn't serve the film's purpose. This is especially dangerous when someone as lovely as Shima Iwashita is in the cast, playing both Jihei's lover Koharu and his neglected wife Osan.

It would take a hell of a lot of obviously artificial sets to keep me from losing myself in images like that. Fortunately, Shinoda has a secret weapon: ohaguro!

I wouldn't call that a Brechtian technique, exactly, but it certainly made me pull back from the screen. Joking aside, Shinoda pulls out all the stops to make Double Suicide as artificial and theatrical an experience as possible: odd compositions, 180-degree-rule breaking, bizarre sets, freeze-frames, and of course, puppeteers running from scene to scene in the background. Even his blocking is overdetermined to the point of distancing the audience. Here's how he handles a simple conversation between Koharu and Tahei, an obnoxious merchant played by Hôsei Komatsu. The camera picks up Tahei on the right side of a wide shot as he enters the brothel:

It pans left, following him across the floor, until he stops so that Tahei, Koharu, and the brothel's madam form three evenly-spaced vertical lines:

Koharu moves forward toward the camera before sitting; Tahei slouches where he is. The frame's symmetry is broken...

And then restored when Shinoda cuts to a different angle.

Note that Shinoda is close to violating the 180 degree rule here: the camera is now on Koharu's right. And the madam's position on the set has changed—although she moves forward at the end of the preceding shot, her left shoulder is still behind Tahei. In this shot, she's clearly in front of him. So the cut makes geometric sense, but it's just awry enough to feel a little off.

To hammer in the point that these are very carefully composed two-dimensional images, Shinoda does something I've never seen before. The madam stands up and walks off screen, crossing between Tahei and Koharu:

She then enters the frame again, from the right, crossing in front of Koharu:

Before sitting down again, in precisely the right spot so that her head takes up the same space in the frame that her body did before.

From here, we go to a shot that is ostensibly from Tahei's point of view; but the camera is closer than he is, giving us this striking framing of Koharu's head. Note the way the madam's head and the edge of the stairs balance the shot.

They turn towards the camera simultaneously, maintaining the frame's symmetry:

And then we get the one shot in this sequence that could belong to another film, a direct eyeline match between Koharu and Tahei:

Followed by another nicely composed deep shot: note that the madam and Koharu are much farther away from each other than they were before.

So what's so bizarre about this sequence that it warrants breaking it down shot by shot? For one thing, there's no master shot. The opening shot that pans left as Jihei enters the brothel is the closest thing to a master, and Shinoda never returns to it. When he does return to a wide shot, it's from a different position. I would be quite surprised if the actors ever ran through the entire scene in one take. Second, if you try to map out where everyone is in three-dimensional space, you quickly realize that people are moving between shots. On a first viewing, the overall effect of these changes between cuts is just a vague sense that something is off about the way the scene is shot—a more subtle version of Scorsese's water glass in Shutter Island. The point is that the blocking doesn't make a whole lot of sense in three-dimensions. In two dimensions, on the other hand, everything snaps into precise shape. Which can't help but remind you that you're watching two-dimensional projections of light, not prostitutes and their clients in a brothel.

So why do this? Why go to such great lengths to keep the audience from identifying with the characters, from losing themselves in the story? Well, if you don't identify with the characters and get lost in the narrative (and trust me, you will not be lost in Double Suicide's narrative), you are much more likely to think critically about how and why it is constructed the way it is. Brecht's goal was always to point out the underlying social and political structures, and most writing about the film (e.g., Aaron Cutler's notes on a Shinoda retrospective) ascribes similar motives to Shinoda. As Cutler puts it, the film "pushes its social injustice so forcefully that the only response is to want to push back." I think that might be true of The Love Suicides at Amijima, but I'm not convinced it applies to Double Suicide. Maybe the distancing effect worked a little too well on me, but the societal pressures bearing down on Koharu and Jihei seemed as artificial as the sets—and half as well constructed. Koharu and Jihei aren't doomed by their society. It's the puppeteers who build the gibbet.

The great innovation of modern tragedy is the illusion of choice. No matter what Oedipus does, he brings his fate inexorably closer, but, star-cross'd or not, Romeo and Juliet's deaths have considerably more to do with chance—if only that messenger had arrived in time! But surely we lose something important when we trade fate for happenstance. Maybe it could have all turned out differently for Romeo, Juliet, Koharu, Jihei. But that wouldn't make a very good story—something in us needs these things to go badly.

So how do you write a tragedy in an age where people believe "Invictus?" It's a little too late in the day to go back to theism or predestination. We're all genetically fated to grow old and die; that's a tragedy, but it's not a story. I am increasingly convinced that David Simon is correct: "the triumph of institutions over individuals" is the natural form for contemporary tragedy. Institutional inertia is as close as any of us will get to fate. The genius of Double Suicide is that it suggests that narrative itself is an institution. As the film moves towards its inevitable conclusion, Shinoda goes out of his way to suggest that the puppeteers are conflicted about what they're doing. There's no reason to show that conflict if you're interested in dramatizing a clash between personal desire and societal duty in 18th (or 20th) century Japan. There's every reason to show it if you want the audience to ask why we tell ourselves these kinds of stories; what we get out of watching Koharu and Jihei march off to die. As the double suicides promised in the title become more and more inevitable, there are increasingly frequent shots of one of the puppeteers (Shinoda himself?) looking on in anguish. But still he moves the sets and props around. These stories have rules.

Randoms:

- There's a graduate thesis or two to be written about Shinoda's decision to cast his real-life wife Shima Iwashita as both the dutiful wife Osun and overtly sexual prostitute Koharu.

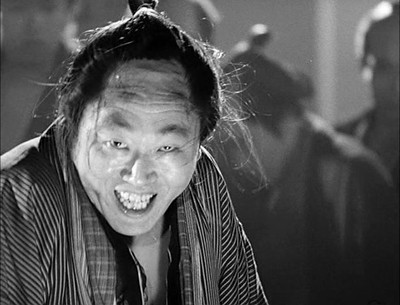

- Hôsei Komatsu plays Tahei as kind of a jovial asshole, so it was a surprise to look over his IMDB résumé and see what appear to be mostly crime films (and the intriguingly named Female Convict Scorpion Jailhouse 41). But there's one scene where he unleashes the crazy and you can see why you'd cast him as the heavy.

- There's a brief interview Shinoda and Shima Iwashita gave at UC Berkeley here. I was struck by this passage:

There is a famous photograph of General MacArthur standing with the emperor and that made it absolutely clear that the emperor was no longer a god, and also it was obvious that that was conscious effort on the part of the Occupation to make that statement.

He was a teenager when that photo was taken. You're never too young to ask yourself who's telling a story, and why.

16 comments:

I haven't finished yet what is already an other great review from you, but I want to pick a tiny bone in your opening line. A lot of cinema(particularly the experimental sort)owes itself to Brecht and to a lesser extent Beckett. The later was actually involved in a film appropriately enough called Film with his cinematic compatriot Buster Keaton. Brecht even more so has relations with film. Some of the more popular acting styles like with Vincent Price and Malcolm McDowell are/were deliberately Brechtian. To a lesser extant you have the likes of Godard and Lindsay Anderson as directors just to name two of the most famous examples. There are more examples from both of those styles being worked into film though I suppose your point about the differences does ultimately stand true even if not to the degree you suggest.

Excellent review. You may be interested in exploring the influence of the dance form 'Butoh' on other Japanese films, in particular certain surrealist exploitation horror movies. There's a great doc you could kill a little time with here: http://wildgrounds.com/index.php/2010/04/27/documentary-on-butoh/

Also, I was wondering if you had any thoughts on the lip-service Charlie Kaufmann (sp?) tries and gives Brecht in some of his movies? Synecdoche, NY is probably the best example off the top of my head?

i think this is going to join the chorus as it were but i think brecht provides the demarcation between american and european cinema. you are right that cinema owes more to vaudeville but i would say that american cinema does that more and certainly continues to do so. or maybe this is my continuing delusion that cinema outside of the united states is normally above the easy and the superficial. but then again, i can't help but notice that lars von trier thrives well in europe and yet when harmony korine does the same thing in the united states, he remains in the niche ... though it doesn't help with the subject matter but i digress =]

This is another sensitive review. I have problems with the assumptions behind notion of "distanciation," among them your assertion that without it audience's "forget they're watching a movie." I think fictions, including films, offer audiences multiple levels of engagement, which can coexist. To take a familiar example: we can worry over the fate of Luke Skywalker while still admiring the special-effects work as such.

That aside, I think you may have misunderstood the film's title a bit. The "shinjü" or double suicide is a highly conventionalized theatrical and literary trope. Audiences would be well aware that plays and stories of a certain type would end in this fashion. The pleasure was not necessarily in the mystery of how the story would end, but in the power and felicity of the telling. So a certain level of self-consciousness would have been apparent in almost any version of this story, many of which had "shinjû" in the title. You can see Shinoda's film as an exercise in Brechtian distanciation--and that may be how Shinoda explained it himself--but you can also see it as Shinoda's attempt to "do something different" with very familiar materials.

By the way, for an even more disconcerting experience, find the film "Sonezaki shinjû" (Double Suicide at Sonezaki) directed by Midori Kurisaki in 1980. It's actually a filmed bunraku play--that is, with actual puppets. However it's not simply a film of an integral performance, one that respects the theatrical proscenium. The puppets move through a realistic, albeit miniature, mise-en-scène of homes, forests, ponds, and so on. You can see the life-size, black-robed puppeteers hovering in the background the whole time.

Finally (phew), if you want see a cryptic, poker-faced, modern-dress parody of the shinjû, search out Kitano Takeshi's "Boiling Point."

Legato,

I completely agree that some films draw from Beckett (especially Beckett films—in my ambitious college days, I tried to produce a version of "Eh Joe," recorded the voiceover, never filmed it). But I wouldn't say that's a lot of cinema and I wouldn't say Film is something a lot of people have seen—it isn't even on Region One DVD. But point taken; I didn't mean to say that no films drew from Brecht or Beckett.

I'm both intrigued by and skeptical of your claim that Vincent Price's acting was Brechtian. I thought what he did was just standard pre-method acting. Could you elaborate on that?

Le Ted,

Thanks for the documentary link -- I'll watch it at work tomorrow. As far as Kaufman goes, I must confess that I still haven't seen Synechdoche, New York; I read the screenplay and was baffled by it. So I don't have much to say about that. I love Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Adaptation, but I wouldn't say either is Brechtian. But if you can make a case for me watching Synechdoche post haste I'll move it up in the Netflix queue!

DJProject,

There's certainly a tradition of art & experimental film abroad that's not as strong here, but if you really think European films are normally above the easy and superficial, I insist you spend some time with Italian comedies. It's just that the easy and superficial foreign films usually don't get released here.

You're definitely right that an audience is more likely to sit through an experimental film by Lars Von Trier than Harmony Corine, and that probably has something to do with his foreign pedigree.

Jonah,

I guess I feel like Shinoda goes out of his way to stop the audience from getting too invested in the power or felicity of the telling, you know? But I take your point that it wasn't necessarily a bold move to title the film Double Suicide.

Thanks for the film recommendations--I've put "Boiling Point" in my queue but "Sonezaki shinjû" doesn't seem to be available. Which is just as well, since I find puppets kind of creepy. Muppets, on the other hand...

First things first Beckett was actually severely indebted to cinema. The only two sources of inspiration I recall him claiming is Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy. I'm sure without movies Beckett would have grown into a drastically different playwright.

As for film that is indebted to him, much as Film hints to, much of the modern minimalist movements are Beckett like. The big difference is that the cinematic Becketts replace camera movement with dialouge. The example most would be familiar with is Gus Van Sant whose Gerry is basically a silent waiting for Godot. Before him though you have the Hungarian directors Jansco and Tarr(who influenced van Sant). If I went about all of the Taiwanese and Iranian directors that owe him a favour we'd be here all day. Let's just say Beckett had and to an extent still has a symbiotic relationship to cinema.

You really didn't bring it up but I think cinema owes Brecht even more a pat on the back with even Tony Scott having elements of Brecht(even if he claims Pinter and Jansco). Going to your second comment though Price much more deliberately than most actors or even stars was performance. He never played those characters, but the character of Vincent Price. Watch any of his post-House of Wax films and than compare it to Laura. The performance while ingrained in basic film acting methods is still ingrained with the thought that people want to see Vincent Price not the character as in the script. In fact that was his biggest argument with the director of Witchfinder General. Price wanted to do his typical Brechtian thing while Reeves wanted a more convincing and traditional performance(in this case I'm glad Reeves won out).

One of the things I've noticed with your statement in this post is that you're focusing on the screenplay aspect when those modernist aspects in film are better communicated through film techniques. I've actually been watching the Beckett on film project recently and the only problems I'm finding in most of these adaptions is how their not directed with a Beckett eye. What Beckett, Brecht, or any of the other theatrical modernists wanted to accomplish would need to be overhauled like how Beckett overhauled his style in Film to properly be communicated. Hopefully that last bit wasn't too long winded or unnecessarily complex.

again this is why i said it's my delusion =]

but yes you can find crap outside of the united states ... you mentioned italian comedies but i would add italian exploitation films and italian rip-off films too =]. and likewise you can find gems inside of the united states ... citizen kane or the godfather anyone? good is good regardless of origin =D

Interestingly, Alexander MacKendrick spent many years trying to adapt Ionesco's Rhinocerous for the cinema, unfortunately without success.You can almost imagine the studios saying 'Ionesco, who?' Or, more likely, oh yeah, Ion... Great, great guy...') It was one of his great unrealized projects (along with Mary, Queen of Scots) and a real pity.

I have seen his production file and carful stryboeard and he really seemed to have captured Ionesco's snese of the absurd impinging on reality on many levels.

Legato,

That's fascinating, and yes, clearly Beckett owes a hell of a lot to silent film. I don't know Jansco or Tarr; I've addded Damnation to my Netflix queue; it looks like The Red and the Black is available over Amazon Instant, so if I can figure out a way to watch that on my television I might check it out as well.

I wouldn't say that Vincent Price playing Vincent Price is a Brechtian technique, unless that's true for every movie star (especially Cary Grant). Witchmaster General is now in my queue as well.

I can't imagine most of Beckett's plays working well on film; I watched some of the films made of the Beckett festival in the 90's when I was in college and they didn't really do much for me. Of course, those were basically one-camera-aimed-at-the-stage productions. Do any of the productions on Beckett on Film particularly stand out to you?

djproject,

Yeah, the Italians make a surprising number and variety of terrible, terrible films. And variety shows!

Richelieu Jr.,

I would pay just about anything to be in a pitch meeting for Rhinoceros.

The UK editions of Jansco's films are great, cheap and R0 if you enjoy what you see with The Red and the White(my personal favorite though is The Roundup.

In the case of Price I think it's a bit more complicated than playing himself. If anything the real comparison would not be to Grant, but Gallo. It's a sort of performance art.

As for the Beckett on Film project there aren't any particularly bad ones. Not I and Play make certain creative decisions that I think go against the intentions of their respective plays, but they're at least entertainingly done. Oddly my favorite from the set could be argued to have the same problem, but since it's only in the end I feel comfortable with it. That adaptation is the Ohio Impromptu by the way.

I loved this review and found your breakdown of that one scene particularly valuable. I hadn't noticed any of those blocking and camera techniques before.

Watching this film was a strange experience for me. I generally hate overly theatrical films and I really don't care for Brecht, yet I loved this movie. It's interesting that, though the film does its utmost to produce a sense of alienation, I always felt very sympathetic toward the characters and very concerned about them. I don't know if that technically means the film failed to do what it set out to do, but it certainly made the experience much more pleasurable for me.

Post a Comment