The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928, directed by Carl Theodor Dryer, written by Joseph Delteil and Carl Theodor Dryer.

I've watched this movie five or six times in the last few weeks, and I haven't come close to plumbing its depths. It's searing, harrowing, pick your adjective. I've been trying to describe the effect it had on me, the experience of watching it, and I don't think I'm a good enough writer by half. So let's stick to the facts.

First we can rule out what it's not. The Passion of Joan of Arc is not The Messenger or anything like more recent treatments of Joan's life. Dryer doesn't give a damn about Joan's military exploits. No one plays the Bastard of Orléans or Charles VII. The Hundred Years' War could be the Twenty Minutes' Disagreement for all the difference it makes to this film. Of course, you wouldn't have needed much context, in France, in 1928. Joan's ecclesiastical rehabilitation was finally complete; excommunicated in her lifetime, she had been canonized in 1920. Joan's status as military hero had been used as a call to arms throughout France during World War I, particularly after the Germans bombed Reims cathedral. Here, she's triumphing over a silent-movie-villain looking Kaiser Wilhelm:

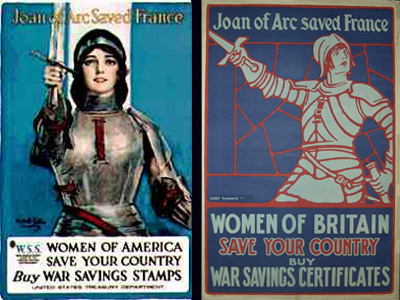

Joan was also used to drum up support for the war in the United States and even (demonstrating somewhat selective memory of her achievements), Great Britain:

And I would only be a little surprised to find her on a German recruiting poster ("Joan of Arc Slaughtered the British. Women of Germany..."). So you wouldn't have needed much context. But Dreyer didn't make a film about Joan as national hero, savior of France; his film could really have been set anywhere. And he didn't make a biopic. Instead, The Passion of Joan of Arc ignores the more obviously cinematic parts of her life and deals exclusively with Joan's trial for heresy in the late winter and early spring of 1431. The movie does have a reverent attitude toward Joan, but it's a different kind than France had at the time. Compare Joan's depiction in the recruiting posters with Dreyer's first shot of Maria Falconetti playing her:

Both the camera and the monk to her right look slightly down on her, she takes up less than a quarter of the image, and she's framed by her captor's weapons. Throughout the film, we will see Joan behaving intelligently and honorably, but not heroically. The Passion of Joan of Arc is not a French version of Henry V.

The Passion of Joan of Arc is also not The Passion of the Christ or anything you might find in the Lives of the Saints. This was something of a relief for me; narratives of martyrdom have always struck me as a little vulgar, satisfying our base instincts while claiming to appeal to our higher ones (for a quick example of what I mean, check out Henryk Siemiradzki's A Christian Dirce; the nicest thing you can say is that the painter's attitude is conflicted). I haven't seen The Passion of the Christ, so I'll stay out of the debate about the explicit torture scenes, but here's Gibson describing why the movie is so violent:

So that they see the enormity—the enormity of that sacrifice; to see that someone could endure that and still come back with love and forgiveness, even through extreme pain and suffering and ridicule.There's an assumption here that by witnessing suffering we come to a better understanding of it. Martyr, after all, comes from the Greek for "witness." Gibson further seems to be asking the audience to consider what it would be like to undergo the same sacrifice (someone could endure that"). The Passion of Joan of Arc doesn't work that way. We are continually denied the ability to identify with Joan; and whenever we reach the comfortable assumption that we know more about her than her judges and tormentors, Dreyer yanks the rug out from under us. One of the ways he does this is (again) through the complete lack of context; but this time it's lack of visual context, not historical. Consider a single line, about halfway through the movie:

This is roughly a point of view shot, from Joan's perspective. On close examination, there aren't that many; usually the camera is closer than she is. The judge says (in the intertitle), "Don't you see that it's the Devil who has turned your head..." and we cut to Joan:

So far, so good. The shot is noticeably off from the judge's perspective (the camera is a little lower and to his left, if we assume that the preceding shot was Joan's POV). This would be a typical way of shooting a scene, if the director wanted us to identify with Joan: modify the standard shot-reverse shot so that one shot is from Joan's POV and the next is third-person. But then we cut back to this:

...right before the judge finishes his sentence with "...who has tricked you?" Now we're not looking at the scene from any perspective at all. Assumptions we were making about knowing how sitting there felt to Joan aren't valid. "Who has turned your head, who has tricked you," indeed. Dreyer cuts back to the earlier shot of Joan, before revisiting the "point of view" of the first shot, with a difference:

But now we're uncomfortably close, and again, clearly not seeing things from Joan's perspective. And then the last shot of her:

As Mark Twain might say, the 180° rule is not just broken, but flung down and danced upon. The result is disorienting and a little exhausting. Notice also, that nothing carries from one shot to the next. That's Dreyer's strategy throughout; as David Bordwell pointed out (via Roger Ebert): "Of the film's over 1,500 cuts, fewer than 30 carry a figure or object over from one shot to another; and fewer than 15 constitute genuine matches on action."

Let me be clear; although we are denied the ability to truly identify with Joan, I don't think we're implicated with her judges. To me the film seemed to have more to say about the impossibility of identifying with anyone at all, especially at the last extremities of faith and suffering. Here's a telling exchange during Joan's first interrogation. The judges, trying to trick Joan into blaspheming, ask the following:

"You have said that Saint Michael appeared to you. In what form? Did he have wings? Did he wear a crown? How was he dressed? How did you know if it was a man or a woman? Was he naked?"

Joan replies only to the last question, "Do you think God was unable to clothe him?" When asked if he had long hair, she answers, "Why would he have cut it?" This is treacherous: Joan is dodging her interrogators, but also making the point that her experiences are incommunicable. Language is inadequate to describe her visions. You will not find many narrative films with as little faith in storytelling as this one. To the extent we try to judge or understand her, we're in the position of their interrogators, who are uniformly as old and unattractive as the one pictured above. You'll notice that I don't refer to any of them by name: although they have names in the screenplay, they're never referred to by name on screen and frankly I'm not sure who's who. But that's sort of the point; they're barely distinguishable. They don't always look angry, though; from time to time, they smile at Joan with infinite condescension:

That's the face of a man who knows he's right. But as I've already noted, we don't really get to identify with Joan, either. So where does that leave us? One way of reading the movie would be to see it as Nabokov saw Cervantes:

The author seems to plan it thus: Come with me, ungentle reader, who enjoys seeing a live dog inflated and kicked around like a soccer football; reader, who likes, of a Sunday morning, on his way to or from church, to poke his stick or direct his spittle at a poor rogue in the stocks; come... I hope you will be amused at what I have to offer.

That would put us back in Passion of the Christ territory, though, and that's not what Dryer is up to either. Although the film does invite us to watch Joan's tormentors slowly and methodically destroy her, and although the experience is extremely unpleasant, we are explicitly asked not to consider her judges as garden-variety sadists. One way Dreyer does this is by putting a few garden-variety sadists in the film: Joan is tormented between interrogation sessions by her jailers, including this upstanding fellow:

I suppose it's the difference between Pilate and the Roman soldiers, an analogy Dreyer makes explicit when Joan's jailers force her to wear a straw crown:

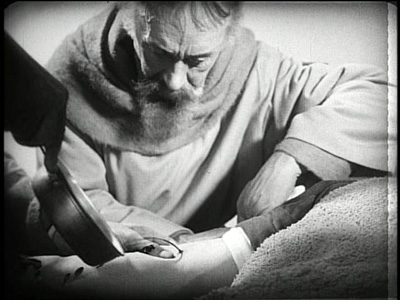

The church officials don't take pleasure in destroying Joan the way her jailers do. But Dreyer suggests that the compassion of the church is worse. One of the monks rescues Joan from the jailers, sends them angrily away, and wipes her tears. Then he takes her to the torture chamber.

So: we're not being asked to watch Joan's destruction for our own pleasure. We can't understand what she's going through, but we're not really implicated or invited to judge her. What's left? I would suggest that one thing the film teaches is compassion, in the older sense of the word (suffering along with). Here's Joan at her lowest point, after she has signed an abjuration she does not understand, denied that her visions were divinely inspired, and been sentenced to life in prison. One would think that her torments were over, but Dreyer cuts from her sentencing directly to this:

It's impossible to watch this penultimate humiliation without wanting to do something, anything to stop it. This is the polar opposite of Cervantes trying to amuse us with cruelty. The Passion of Joan of Arc cuts to the quick of what it is to be human; what, exactly, we have in common with Joan, despite the fact that her experiences are incommunicable. It's worth noting that the judges feel this, too. When Joan recants her abjuration and condemns herself to death, her murderers weep. But they kill her anyway, because they believe they serve something more important than humanity. Joan signs her abjuration when she is most reminded of her own mortality, facing execution and confronted with a maggot-filled memento mori.

Mortals have one thing in common that transcends all ideology; we're headed to the same place. You're thinking, reading this, that the historical Joan would have disagreed with it. The point of the "vast, moth-eaten musical brocade" that she and her captors agree on is that it promises something beyond becoming worm food. And Joan was no anti-ideologue; she killed for her beliefs, and in the end she dies for them. After she burns, the closing intertitles tell us

The flames sheltered Joan's soul as it rose to heaven—Joan whose heart has become the heart of France... Joan, whose memory will always be cherished by the French people.

That suggests, in a few seconds of screentime, that her martyrdom, and the French identity it engendered, somehow made the agony we've been watching for the last ninety minutes "worthwhile." Although she suffered, her country benefited. But this is undercut by the chaos surrounding her death. Those French people who cherish her, who share her heart, are driven into an ecstasy of rage at her death and rebel against their British captors. The British cheerfully slaughter the lot of them.

As far as we see on screen, Joan's death only brings more death, her suffering more suffering. And although we may wish to stop it, we can't even understand it. The Passion of Joan of Arc is the rarest of films, the kind whose violence does not desensitize, but instead raises sensitivity to an unbearable pitch. While Joan burns, Dreyer abandons the closeups and sharp focus he's treated her with in earlier reels. She is obscured by smoke, then by flames. In the end, this is all the mercy the film can offer. The camera's ability to record suffering does not exceed our ability to withstand it.

Randoms:

- Maria Falconetti's performance is the best I've ever seen. And it's her only major film role; if you're going to be on film just once, you could do worse than this. Dreyer wrote about her, "In Falconetti, who plays Joan, I found what I might, with very bold expression, allow myself to call 'the martyr’s reincarnation.'" His phrase seems fair. Her eyes are impossible to meet.

- One bit of trivia about Falconetti; the film was shot in sequence, and she had hoped to convince Dreyer not to cut her hair by the time they got to that scene. So she's genuinely miserable there.

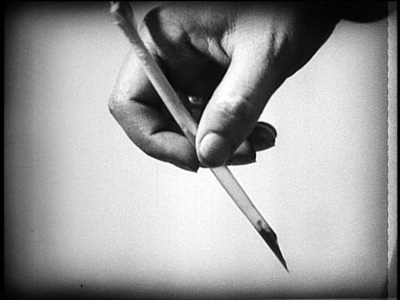

- Rudolf Maté's cinematography is, as you've already noticed from the stills, stunning. He used new-at-the-time panchromatic black and white film, which allowed him to shoot without using makeup. In fact, Dreyer forbid his actors from using it throughout the shoot. One thing you don't get from stills is the remarkably fluid camera movement. Watch for a beautiful tracking shot that follows the judges as they whisper a question to try to trick Joan with:

- The camera pans right as each whispers to the next, much more smoothly than in other films I've seen from this time.

- The composition of this shot (and the flat, oddly proportion backgrounds throughout) reminded me of Giotto:

- And the lighting, while anachronistic for Joan's trial, often recalls Caravaggio.

- Even the insert shots are beautiful:

- I think that the beautiful photography (and the rhythmic, methodical editing) has a great deal to do with the film's effect; together, they give it the feeling of a dance. And the more Joan's suffering seems planned, methodical, and inexorable, the more you consider why she is suffering.

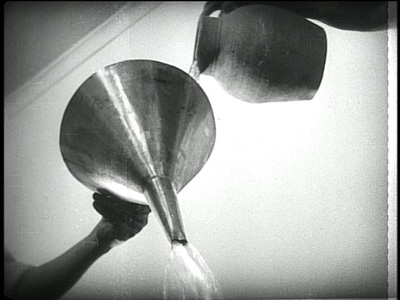

- One of the United States' new favorite alternative interrogation methods makes a cameo:

- Since this one's a "no-brainer" when lives are at stake, imagine how easy it was to do when souls hung in the balance!

- The film's provenance is as muddied as Joan's history. The original negatives and all extant prints were lost to fire; Dreyer recut the film using alternate takes, and then that version was burned, too. All people had seen were bastardized, recut versions; one was dubbed, one had the intertitles superimposed on still shots of churches and stained glass, &c., &c.. Then, in 1984, a print of the original, long lost cut, turned up in a closet in a Danish mental institution. I'm not making that up. The Criterion version is from that print. I'm curious about the discoloration you see in the right side of each frame. The print would have been separate reels, but it seems to have affected all of them.

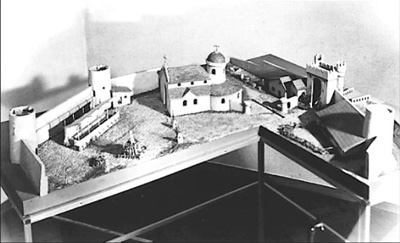

- Exteriors on The Passion of Joan of Arc was filmed on one of the most expensive (if not the most expensive) exterior sets of the time (at least in Europe). And it's almost completely invisible, given Dreyer's penchant for close-ups. Here's a model of its layout, the only way to see the whole thing.

- Note to aspiring filmmakers: spending millions on a set that you don't shoot is the kind of thing producers love.

- It's a commonplace complaint that film productions run on the blood of underpaid and underappreciated production assistants, but no one took this quite as literally as Dreyer.

- Someone donated their vein for the bleeding scene. That's not an effect, that's an actual arm shedding actual blood. In fact, disgustingly enough, one of the ways to identify the second cut of the film, the one from alternate takes, is that the blood doesn't spurt as much:

- Because of course by the time they got to that take, the PA's blood pressure had dropped. From all the bleeding. I thought the worst story along those lines I'd heard was that a PA was tased on the set of Hannibal when no actor or stuntman was dropping as fast as Ridley Scott would have liked (the way I heard it, the PA got hazard pay and a chance to hang out and talk about movies with Ridley Scott; not a very good deal). But The Passion of Joan of Arc takes the cake.

- This is a strange question, but it's been bothering me since I saw the film. Can anyone identify the graffito on the wall in this still?

- Here it is blown up:

- I know I've seen this creature, drawn in this style, somewhere before, but I can't remember where.

- Dreyer hated having his movies shown with musical accompaniment (and the DVD actually has an audio track that has nothing but silence on it; you would think viewers could just hit MUTE). I am going to go ahead and advise you to ignore his wishes in this matter, though, because the second audio track sets the film to Richard Einhorn's "Voices of Light," an "Opera/Oratorio," as the DVD has it, inspired by The Passion of Joan of Arc. The music is beautiful, haunting, wonderful; it suits the film perfectly. The pace of the editing is perfectly matched by the methodical counterpoint in Einhorn's score (particularly during her early interrogations and the scene in the torture chamber). Even if it wasn't written to be a score to the film, precisely, it goes down as one of the best silent film scores ever.

- If I haven't made it clear enough by now: WATCH THIS MOVIE, PLEASE. You'll wonder how you lived so long without knowing it backwards and forwards.