In Frank S. Nugent's review of Alexander Nevsky for the New York Times, he wrote that Sergei Eisenstein had a "talent for doing great things so well and little things so badly." Nugent (who went on to write The Searchers, among other films), had Eisenstein dead to rights. Alexander Nevsky is a frustrating film, in which moments of technical genius are all too often overshadowed by insipid writing and characterization. To be fair to Eisenstein, however, he wasn't exactly given free reign, as the opening titles make clear:

That's the logo for Mosfilm Studios. MGM had "Ars Gratia Artis," but the Soviets had to make do with "Worker and Kolkhoznitsa." And while working for Mosfilm was never conducive to artistic freedom, Eisenstein had less leeway than most, due to the failure of his previous film, Bezhin Meadow. After two years of production, reshoots, and more reshoots, the whole mess was shut down for being insufficiently ideologically correct. Bezhin Meadow had as its hero a Young Pioneer who de-kulakizized his own family, turning his father in to the state, but even a celebration of informers wasn't good enough for Mosfilm. After it shut down, Eisenstein came down with smallpox and the flu, and then wrote an apologia filled with turgid nonsense like this:

The mistake is rooted in one deep-seated intellectual and individualist illusion, an illusion which, beginning with small things, can subsequently lead to big mistakes and tragic outcomes. It is an illusion which Lenin constantly decried, an illusion which Stalin tirelessly exposes—the illusion that one may accomplish truly revolutionary work "on one's own," outside the fold of the collective, outside of a single iron unity with the collective.

So when it came time to write his next screenplay, Eisenstein collaborated with Pyotr Pavlenko, a member of the secret police who allegedly sat in on NKVD interrogations. American filmmakers bitch and moan about dealing with Philistine studio executives, but at least those guys only pretend to be bloodthirsty madmen. To say Eisenstein was operating from a position of limited power is an understatement. It's not a surprise, then, that Alexander Nevsky is unsubtle and clumsy in its ideology. The real wonder is it wasn't titled Please Don't Kill Me, Comrade Stalin.

Trying to find the least politically controversial subject to make a film about, Eisenstein settled on the life story of a thirteenth century Russian prince, best known for defeating the Livonian Order in a battle on a frozen lake in 1242. Like Olivier's Henry V, Eisenstein's Nevsky is a straightforward hero. We can tell this from the first time we see him, bestriding the narrow world like a colossus, arms akimbo:

Actually, Nikolai Cherkasov plays him as someone who spends a lot of time with his arms akimbo:

I mean a lot of time with his arms akimbo:

The trustworthy looking Asian gentleman on the left is a representative of the Golden Horde (I believe that he's probably Hubilay, which would make the actor Lyan-Kun). And Hubilay is treated sympathetically compared to the knights of the Livonian order. George Lucas learned a great deal from their introductory scene. Cherkasov's Nevsky may be overdoing it a little on the heroic posturing front, but then, you'd have to overdo it if you were going to fight these guys:

That's the first shot we see of the knights. Wikipedia identifies them as the Livonian Order, which was part of the Teutonic Order after 1236; Eisenstein just calls them the Teutonic Order, so that's what I'll do. Anyway, Eisenstein introduces them with still shots, while Prokofiev's score hits minor notes that make the Imperial March sound like the Pastoral Symphony. Those guys are the knights; they're accompanied by the equally dehumanized foot soldiers.

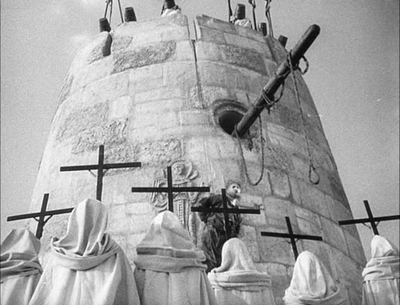

Just when you think Eisenstein is going to cheat and make the Germans all robotic automatons, he shows us a refreshingly human face: Naum Rogozhin as the Black Monk:

And finally, the crème de la crème, Germany's Next Top Knights and their spiritual leader:

The only question is whether Emperor Palpatine most resembles the Lev Fenin's Archbishop or the Black Monk. My money's on Fenin, because he seems like the more dissolute of the pair:

So: not a very pleasant group of people, these guys. But like I said, this isn't a subtle movie. In case we didn't catch on that these are our villains, we immediately get to see them throwing young children into bonfires.

Brief, and to the point. Alexander Nevsky is structurally closer to television than most films; it has a clearly designed A and B story. The A story, obviously, is Nevsky versus the baby-killers, and although it contains not a lick of subtlety or ambiguity, it's relatively well-executed. The B story, on the other hand, suffers greatly from terrible writing and terrible haircuts. It's about a young woman trying to decide between two suitors, which is usually a rich enough idea for its own movie. But in this case, the young woman (Vera Ivashova) appears to be some sort of Kolkhoz fertility goddess:

Obviously, her name is Olga. Olga's suitors are as dashing and well-dressed as you would expect:

I regret to inform you that the hat Nikolai Okhlopkov is wearing looks even worse in closeup.

As you can see, the correct solution to this love triangle is murder-murder-suicide, but Eisenstein spends a considerable amount of time with these characters, and every time they're on screen, the film screeches to a halt. To be fair, Nevsky is as poorly written as Olga and her suitors, but Cherkasov has enough magnetism to still be interesting as a cardboard cutout. Let's just say that love stories are one of the little things Eisenstein does so badly and leave it at that.

So what does Eisenstein do well? Everyone will tell you that the battle on the ice is the best part of the film, but the really spectacular work is not the battle itself, but the charge of the Teutonic knights that begins it. Eisenstein and Prokofiev worked very closely synchronizing the score and editing in more detail that you might imagine. In his essay "Form and Content: Practice," Eisenstein explained that he and Prokfiev attempted to have the score mirror the visual composition of the shots, assuming a left-to-right scanning of each image (viewers who read right-to-left are out of luck). You can see how it's supposed to work in this illustration.

Note in the second shot the way the curve of the cloud is mirrored by the four rising notes in the bass, or the way the descending notes trace the curve of the rock in the fourth shot. Eisenstein called this interplay between sound and image "vertical montage," distinguished from the horizontal montage created by a group of shots. If this seems needlessly intricate and more than a little pretentious, keep in mind that the model here was not "A Dialectical Approach to Film Form" so much as it was "Silly Symphonies." Russel Merrit traces the connection between Eisenstein, Prokofiev, and Disney in one of the DVD's extras, which includes this excellent shot of Eisenstein and Disney outside Disney Studios:

Animation was the only realm of film where the soundtrack was as carefully synchronized as it was in Alexander Nevsky, although the goal was usually comedy, not some kind of abstract mapping of the visual space of each shot. Suffice it to say that they all learned from each other. The theoretical aspects of "vertical montage" are less interesting than the practical effect: the charge of the Teutonic Knights is one of the best scored sequences in film. Barring any YouTube difficulties, you can watch a low-res version of it right here:

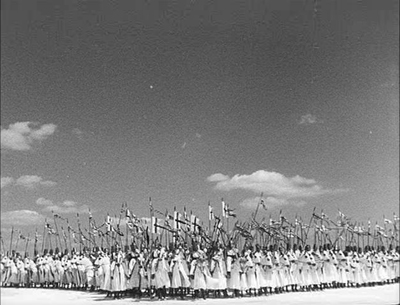

You can see just how amazing the Prokfiev/Eisenstein collaboration was at its best. As bad as Eisenstein was at the human stuff, he created magnificent effects when working on an epic scale. A few highlights, in anticipation of YouTube disaster. This will give you an idea of the scale:

The Teutonic Knights advance like a tidal wave, in a shot Pynchon's Blicero no doubt would have appreciated:

As you can see, Mosfilm apparently had quite a large budget for extras.

And even the hokey human interest stuff takes on gravity when set against this backdrop. Here's one of my favorite shots in the film, of Aleksandra Danilova playing a woman who has taken up arms after her father is killed at Pskov. Every other time you see her, she comes off as kind of silly, but here she's unforgettable:

This is Eisenstein at his best, and it's brilliant. It must be said, however, that describing the battle on the ice as the most ingenious sequence in the film is stretching truth. The knights' charge is the good part; once they actually arrive and the battle is met, things get a little silly. Eisenstein cuts in lots of relatively context-free medium shots of characters hacking and slashing their way through the Germans:

Chalk it up again to Eisenstein getting the big things right and the little things spectacularly wrong. The part of the battle where the Germans crash through the ice to their watery doom plays as farce, thanks to the obviously fake ice:

The Germans splash around unconvincingly in the water and then take deep breaths before diving beneath the surface:

The aftermath of the battle brings us much more of the Olga-Vasili-Gavrilo love triangle, which is just as uninteresting as it was before the battle. The film ends with a stirring speech by Nevsky, closing with "He who comes to us with a sword, shall die by the sword. On this stands Russia, and on this she will stand forever." The last shot is a pretty clear warning to anyone who might be thinking of invading Russia around that time, particularly anyone, shall we say, German:

If that's how many people their film industry commands, imagine the army!

Alexander Nevsky is not a great film, though it has moments of greatness. The introduction of the Teutonic Order is one such moment, and the knights' charge is another. The character work and the scenes between Olga and her suitors, on the other hand, seem to belong to a much earlier age of filmmaking. When Eisenstein is good, he's very very good, but when he is bad, he is horrid. But given the circumstances under which Alexander Nevsky was made, it's amazing that Eisenstein managed anything watchable, let alone fitfully brilliant. The correct piece of art to compare Alexander Nevsky to is not Pygmalion (released the same year), but "Roses for Stalin."

Watch it right after Pygmalion, and Alexander Nevsky seems hopelessly unsophisticated. But next to the other fruits of Socialist Realism, it's nothing short of a triumph.

- Boris Shumyatsky, the head of Mosfilm who shut down Bezhin Meadow, had his own problems with ideological purity. Stalin had him shot in 1938.

- Alexander Nevsky was popular in Russia right up to August 24, 1939 and then, for some reason fell quickly out of favor. Fortunately for Eisenstein, but unfortunately for the Germans and Russians, the movie had a very successful revival on June 22, 1941. If you have any doubt that Alexander Nevsky was specifically about defending Russia from the Germans, note how much the helmets of the German foot soldiers resemble stahlhelme:

- More to the point, check out the strange symbols on the Archbishop's mitre:

- The photo of Eisenstein and Disney was taken in front of the original Disney Studio, judging from this picture. This means the two men were standing about a block away from my apartment. In fact, as I write this, I'm eating a turkey sandwich from the Gelson's that stands there today. I believe that by continuing to eat turkey from that particular Gelson's carving station, I will eventually take on the powers of both Disney and Eisenstein and rule the world.

- Prokofiev's score was recorded with the kind of sonic experimentation I erroneously believed started with Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. One of many examples: the reedy sound of the battle horns was created by putting the mics too close. But it's hard to tell exactly how Prokofiev and Eisenstein wanted the film to sound, because there's some evidence that the movie was released with a temp audio track. Whether that recording was intended to be the final audio mix or not, it's indisputable Eisenstei wasn't finished editing it. An unfinished version was somehow shown to Stalin, who approved it for release. Probably wisely, no one at Mosfilm would let Eisenstein change a single frame after that.

- The best Nevsky-related YouTube clip is undoubtedly this one, in which a father makes his 1 and 3-year-old children wear cardboard helmets and rock back and forth on their hobby horses like the Germans, while Prokofiev plays in the background. The older kid has an evil laugh.

- Perhaps it's a Russian thing, but like Tarkovsky in Andrei Rublev, Alexander Nevsky has many shots that seem to be designed around abstract geometry rather than more conventional composition. This one, for instance:

- I also noticed that Eisenstein often puts the horizon line way, way lower on the screen than most directors. You can kind of see it in the battle shots above, but here's a sharper example. I don't think I've ever seen anyone frame a shot quite this way:

- Finally, a little-known fact about Mosfilm's Central Casting. If you order 1500 pikemen, you apparently get Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson for free.

- I knew there was something suspicious about a wrestler who called himself the "People's Champion," and now it can be told: WWF is Socialist Realism's greatest achievement.