Ivan the Terrible, 1945–1946, written and directed by Sergei Eisenstein.

I was wrong about Sergei Eisenstein. What I'd seen of his work had led me to believe he was only of historical interest: a master of technical innovations that have since been so thoroughly absorbed into cinematic grammar that they no longer seem remarkable. The person who invented the wheel undoubtedly changed the world of transportation forever, but that doesn't mean you'd like to spend two hours cruising along in Caveman Ug's first cart. Watching Ivan the Terrible was a bit like discovering that, just before he died, Caveman Ug also built a Ferarri. So: I was wrong about Sergei Eisenstein. The Ivan the Terrible films are masterpieces.

Not all masterpieces are things you want to see every weekend, however, and I'd recommend not popping these in when you're looking for a bit of lighthearted fun. Ivan the Terrible is a claustrophobic nightmare, the biopic reimagined as horror film by way of Disney and German Expressionism. Usually when someone says "You've never seen anything like this!" they really mean, "I haven't seen any of the hundreds of similar films, and I'm hoping you haven't either!" I'm as guilty of that as anyone, but I'll say with some confidence that you've never seen anything like the Ivan the Terrible films. They don't seem to have been made by the director of Alexander Nevsky. Actually, they don't seem to have been made on this planet. The first adjective that comes to mind is diseased. Most viewers won't make it through the long, slow opening scene. That's a shame, because the second adjective that comes to mind is indispensable. There are more insightful films about the way power corrodes those who would wield it, or the dangers of giving oneself away to an abstract idea, or even Russia and other totalitarian regimes. But there's something about these two films; they burrow into your head and stay there. And I do mean burrow; the movement of the film is not a disentanglement from, but a progressive knotting into. Every frame the film advances moves its characters closer to a point of absolute malignant stasis. And in virtually every scene, Eisenstein undercuts the traditional tropes of heroic biography, creating one of the most unsettling movies ever made.

The first scene is as good an example as any; Ivan, Prince of Moscow, is being crowned Tsar of All Russias. It's a giant set piece of imperialistic pageantry, and Ivan, wearing the crown for the first time in his life, looks as idealistic and regal as we'll ever see him. It doesn't hurt that he's being portrayed by Nikolai Cherkasov, who audiences would be primed to think of as a straightforward hero, thanks to Alexander Nevsky.

This scene is in dozens of movies, in one form or another. But Eisenstein keeps cutting away from the ceremony to reaction shots of the crowd, of which a few examples will suffice. Notice how carefully composed these images are; the only other film I can think of where every shot is so visually striking is The Passion of Joan of Arc:

Beautiful photography, all in the service of making a viewer ill at ease. I'll go ahead and say it: this movie will make you paranoid. Or in my case, even more paranoid. Even Mikhail Nazvanov's Andrei Kurbsky, nominally one of Ivan's close friends, seems less than pleased by the ceremony.

Eisenstein doesn't give us any context for these disconnected shots of malice and contempt at first, just plunges us into Ivan's landmine filled court. Ivan seems pretty indifferent to the hostility that surrounds him; he just stares off into the distance in the manner of someone who's above it all. Which is literally true, naturally. His first speech at the coronation ceremony has three main planks: he's going to end the "pernicious power of the boyars," he's forming a standing army and giving citizens a choice between conscription and taxation, and he's ending the church's tax-exempt status. Yep: it's basically how Hugh Hewitt imagines Obama's Inaugural Address. The point is not the specifics of his platform, so much as the fact that he's immediately asking his citizenry to sacrifice in the name of the Russian State. You can see in his eyes that he's the kind of person who dedicates himself to noble goals. Or at least that's what he tells himself. We get to see one more moment of pomp and circumstance for Ivan, his wedding to Anastasia Romanovna.

Once again, Ivan is surrounded by people who aren't even trying to conceal their contempt for him, with one exception, his cousin Vladimir Staritsky. Vlad doesn't have an evil bone in his body, mostly because he's a complete moron. Here, he's yelling "Kiss her!" to Ivan, with a mouth full of food.

Naturally, Vladimir is the patsy that the boyars want to put on the throne in Ivan's place. They're led by his charming mother Efrosinia, played by Serafima Birman as almost comically untrustworthy.

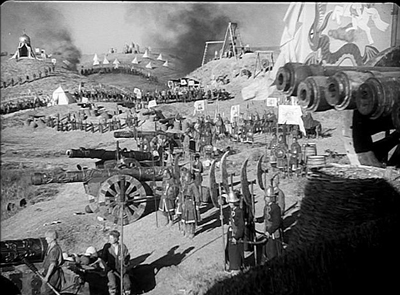

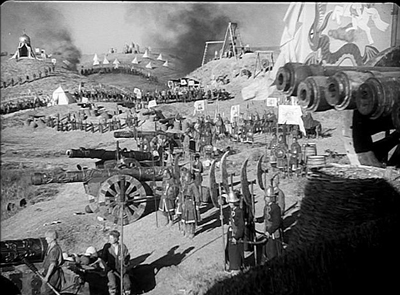

Ivan's wedding ends in classic Russian style: Moscow is burned to the ground, the peasantry storm his castle, Kazan declares war on Russia, and Ivan leads an army off to war. Presumably, the royal wedding planners were all beheaded. From here on out, everything moves downhill and inward, although the early scenes are actually relatively open and broad. The battle of Kazan features some large-scale exteriors that are positively sweeping:

Of course, what we're seeing there are the artillery and troops led by Kurbsky. The battle is won because Ivan relies, instead, on a team of sappers:

As elsewhere in the film, it's all about digging in. The leader of the sappers is one Malyuta Skuratov, who begins the film as a bit of a dunce, a man of vigorous passions and actions; he's always doing things like wiping the sweat off his brow, or enthusiastically rallying people to Kazan:

Ivan senses potential in Malyuta's dumb obeisance before power, and promptly employs him to run his intelligence-gathering operations. The work isn't good for his working-class vigor; by halfway through the first film, he moves through the courts like a wraith, just taking everything in.

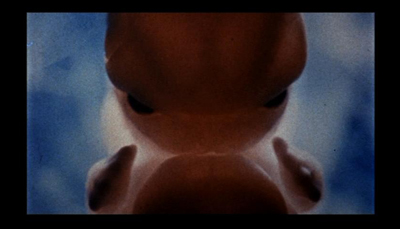

Note that only one eye is in the frame: long before Sauron, Eisenstein had figured out the sinister effects of disembodied eyes.

I suppose living in a surveillance state makes one particularly sensitive to questions of observation, particularly when you're making a movie about another surveillance state. Eisenstein takes every opportunity to shoot his characters with one eye obscured, using props, costumes, and lighting to make cyclopean monsters of his cast.

The shots don't seem to have any significance to the film's internal mechanics: a one-eyed shot doesn't have much relation that I could see to a character's moral status at that point in the film. Instead, the cyclops shots are just a pervasive image that Eisenstein goes back to again and again, heightening the paranoia the films are steeped in. It's worth mentioning at this point that one of Ivan's signature achievements was the creation of the Oprichniki, Russia's first secret police squad. They're led by Malyuta, and they get the same faraway look in their eyes Ivan does when he talks about the Russian State. Here's Fyodor Basmanov, a representative sample:

He's looking pretty happy for someone whose father has just disowned him so he can join the Oprichniki. In the Ivan films (as in life), anytime someone's looking off into the distance, you'd be well advised to stay the hell away from them. When you're looking long-term, a little bloodshed in the here and now isn't worth losing any sleep over. Here's the trifecta:

There's exactly one character who doesn't become more and more corrupt every time we see her, and the narrative treats her just about as kindly as Efrosinia does.

That's Lyudmila Tselikovskaya as Ivan's wife Anastasia, the only character who seems more or less blameless (though like all women in the film, she's been kept from any real power—but leave the question of virtue without agency for another post). Anyway: Anastasia is the film's repository for positive values. She doesn't make it out of the first movie. She asks Ivan for water; he finds a conveniently placed poisoned goblet, and that's that. Efrosinia is to blame, although it should be noted that Malyuta, the "Eye of the Tsar," is looking in exactly the wrong direction when Ivan finds the poison.

The problem with surrounding yourself with people who worship you is that they'll kill your wife (or do nothing to stop her murder) if they think it will bring the two of you closer. And Malyuta, it should be remembered, quite literally kneels at Ivan's feet panting and slavering like a dog.

Things just keep getting grimmer, more constricted, and above all more paranoid. By the opening of the second film, Eisenstein has abandoned any pretense that he's making a biopic. Kurbsky's betrayal of Ivan and surrender to the Poles pretty clearly takes place in some kind of homoerotic fairy tale, not sixteenth century Europe.

Eisenstein had originally planned for his film to open with the murder of Ivan's mother and a lengthy sequence of Ivan's rule as a child, manipulated by the boyars. Mosfilm told him he had to start with something uplifting (the coronation), so Eisenstein used the footage he'd shot in the second film, which is where it belongs. Like Kurbsky's surrender, it's from the world of fairy tales, where parents are lost and guardians are wicked.

The film works better by slowly degenerating into a fairy tale; starting there would have been a mistake. The may be the only instance of a Soviet bureaucrat making a decision that improved art. Except for one other: they gave Eisenstein some Agfacolor stock that the retreating German troops weren't using any more. So at just about exactly the time the film hits the bottom of its moral abyss, Eisenstein gets to use color. He rose to the occasion, and so did Prokofiev: "Dance of the Oprichniks" is the best part of the score. Ivan the Terrible, Part II is the only film besides The Producers to feature a showstopping musical number with a chorus line of mass murderers.

It's not played for laughs. Like Lolita, Ivan the Terrible is filled with "travesties of familial feeling" (Martin Amis's phrase), and Ivan's revels are no exception. Here's the dancer the choreography is built around:

Fyodor in a mask is a pretty obvious example, but Eisenstein goes so far as to create travesties of earlier scenes in his own film. In doing so, he asks more of viewers than most directors. It's impossible to overstate the sheer visual craftsmanship on display throughout these movies. When you see Vladimir—drunk to the point of stupefaction—rest his head on Ivan's lap:

You're meant to think of an earlier shot of Vladimir and Efrosinia:

But that shot was already a travesty of the Pietà. See what I mean about knotting into? Does Eisenstein go all the way back around to sincerity? Well, shortly after Vladimir passes out, we get this:

That looks an awful lot like Ivan as a boy, down to the eye movement; which doesn't bode well for Vladimir. Eisenstein's not done with the Pietà just yet.

Beyond the painstaking visual craftsmanship and the relentlessly self-devouring narrative structure, the staggering thing about Ivan the Terrible is that it's only two-thirds complete. What could Eisenstein possibly have done in the third film to continue Ivan's decline? Well, the historical Ivan beat one daughter-in-law into miscarrying, tried to rape the other, and bashed his son's skull in, so Eisenstein had room to play with. Or rather, he would have, if Stalin hadn't decided that perhaps Eisenstein's portrait of a diseased survelliance state and its batshit crazy, megalomaniacal autocrat wasn't the kind of Russian mythmaking he was aiming for. But even incomplete, Ivan the Terrible is an unqualified masterpiece, a perfect union of form and function. Every scene, every shot, every frame presents a unified vision of humanity in which everyone is a jackal, an imbecile, or both. Happy New Year, everybody!

Randoms:

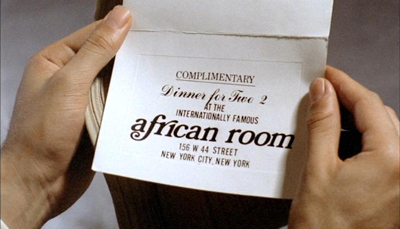

- Ivan the Terrible, Part II features probably the best subtitle in the entire Criterion Collection. I'm not really sure how this even happened:

- Eisenstein had clearly given some thought to the question of how to make the third film even more unsettling than the last, as a few surviving fragments make clear. For one thing, he'd cast Mikhail Romm, then the chairman of the Film Union, in the role of Queen Elizabeth. Cate Blanchett eat your heart out.

I think it's safe to assume that Ivan the Terrible, Part III would have been as unnerving as its predecessors.