The Harder They Come, 1973, directed by Perry Henzell, written by Perry Henzell and Trevor D. Rhone.

In August of 1973, my father and mother moved into a strange little house on Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, where my father was starting law school. The house belonged to an elderly woman who promised her husband before his death that she wouldn't sell the home they'd shared. So while the rest of their neighborhood was bulldozed and turned into office space and retail, her house just sat there. And as Google Maps reveals, it's sitting there today, defying the architecture around it:

My parents had the front of the second floor, which didn't have enough room for a full-sized bed. But like many old houses, this one came with a window seat (pictured) and a terrible curse (not pictured). The curse worked like this: the house was right across the street from the Orson Welles theater. So at least once a week, some moviegoer would park in front of the driveway, blocking everyone in. And that August, the movie that inspired such careless parking was The Harder They Come, which began an unprecedented seven-year run at the theater that summer. My parents have always said that The Paper Chase—opened that October, set at Harvard Law—was sort of their theme movie for the year, but it seems to me that The Harder They Come had a more direct impact on them, in the sense that they kept having to call tow trucks because of it. So full disclosure requires me to point out that this film caused my family actual, measurable harm. But it's impossible to stay angry at a movie with this much low-rent charm.

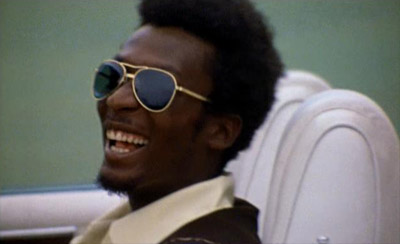

That's Jimmy Cliff, undoubtedly about to park that car in front of my parents' driveway and make my dad late for class. He plays Ivan Martin, a kid from the country trying to make it as a singer in Kingston, Jamaica. Ivan is literally just off the bus:

And naïve enough that the first thing he does is load all of his worldly possessions onto the garishly decorated pushcart of a young man who is nice enough to offer to help him carry them. Here's the last glimpse he gets of everything he owns:

Ivan has big dreams, but not a lot of follow-through. On his first day in Kingston, he meets a gambler who is having a suspicious run of luck at dominoes, and that pretty much sums up his chances. Kingston's economy is a rigged game, and nobody makes it from here:

To here:

Ivan's no exception to the rules, but he makes a pretty good show of trying. For the first half of the film, he moves from one unsuitable father figure to another. The first is a ferocious preacher played with brio by Basil Keane:

You can imagine how well the preacher gets along with a laid-back reggae fan like Ivan—for one thing he thinks the music Ivan listens to is called "boogie woogie." But living here beats the streets, and Ivan at least manages to scrounge up enough money to buy an unforgettable hat.

You can see where this is going; the preacher has a young ward, Elsa, and his intentions toward her are perhaps not as honorable as he tells himself. She's played by Janet Bartley:

So it's no surprise that the preacher doesn't much like it when Ivan starts taking her out for rides on his bicycle (Sidesaddle! In heels!).

Fortunately, Father Figure #2 swoops in to save the day right when the preacher evicts Ivan. He's a music producer named Hilton, who gives Ivan the chance to make a record, out of pure love for music and enthusiasm about the young man's talent. Look up "avuncular" in the dictionary and there's a picture of Hilton:

I'm just kidding. He does it for the money, giving Ivan a take-it-or-leave-it deal on his single: $20 for all rights in perpetuity. Without Hilton's go-ahead, no DJ will touch the record, no matter how good it is, so Ivan eventually signs it away. That's why you need an entertainment lawyer, kids. You think cars like this pay for themselves?

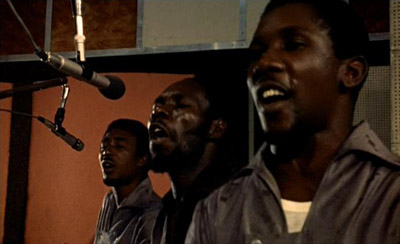

Shitty deal aside, Hilton does let Ivan record a song, which is as close as he gets to his dream. Here he is in the studio; this footage was shot of Jimmy Cliff actually recording the film's title song.

Which brings us to father figure #3, the only constant, reliable thing in Jamaica:

Ivan gets in on the ground floor in what everyone in the movie just calls "the trade," recognizing that there's little else of value coming out of their country. But as with the preacher and Hilton, he chafes against the raw deal he's getting. Unfortunately for Ivan, authority figures in the drug trade stay in power with harsher methods than preachers or record moguls.1

After Ivan kills a cop rather than be pulled over again, the second, weaker half of the film follows him on the run. He doesn't get to be famous the way he dreamed, but he's famous nonetheless. Luckily for Hilton, this means Ivan's record shoots up the charts while Ivan shoots up the countryside. Ivan is the kind of celebrity publicists dream of: he runs a pretty competent publicity campaign on his own behalf, sending the newspapers photos to run.

As you can see, he's modeling himself on Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde. And things turned out pretty well for them, right?

The Harder They Come doesn't have an amazing screenplay, but it floats by on the strength of its other qualities. Almost the entire film is handheld, giving it a documentary feel, which in a way, it is. Henzell didn't hire actors to pick through a garbage heap for this shot, he just let his camera roll.

The further Henzell gets from this kind of documentary feel, the more the film suffers; compare his footage of the dump to this shot, from the knife fight that for me, marks the film's low point.

The realism of the rest of the film drowns in terrible fake blood. The gunfights don't play very well either. That means the second half doesn't work nearly as well as the first, because Henzell has a lot of plot he has to move along, which isn't his strong suit. But in the first half, the realism pays off in narrative terms. Henzell doesn't spend a lot of time exploring Ivan's desire to be rich and famous, becahse he doesn't have to. He simply documents the vast gulf between the upper and lower class in Jamaica, and that does his work for him. All it takes is a few carefully chosen details: Ivan has a copy of Playboy in the burnt out car he's made his headquarters; the first thing he does when he gets to Kingston is go to a Spaghetti Western, he looks longingly at a Stratocaster in a display window. Clearly, Western materialism is not serving him well.

I'm not qualified to judge the relative accuracy of Perry Henzell's Kingston or Marcel Camus's Rio de Janeiro, but The Harder They Come feels a lot more real than Black Orpheus. It's not just the camerawork; Henzell also let his actors speak in unapologetically Jamaican patois, so you'll want to watch this with the subtitles on. And then, of course, there's the music. Just as Black Orpheus brought Latin American music to the states, this was the first taste Americans had of reggae music. And the soundtrack is amazing: Jimmy Cliff, Desmond Dekker, and Toots and the Maytals:

There's no Bob Marley and the Wailers on the soundtrack, but this created a market for "Catch a Fire." I would bet that many more people bought the soundtrack than saw the film, which is actually a pretty fair assessment of their relative merit. The soundtrack is a masterpiece, and the film isn't. But it's still well worth seeing, both for Jimmy Cliff's charismatic performance and Henzell's great footage of Jamaica.

My mother and father would probably disagree with that assesment. In all the time they were in Cambridge, they never crossed the street and bought a ticket. As far as I know, they never bought the soundtrack either. Maybe they didn't want to support the business that kept blocking their driveway, maybe they never found time, or maybe the dealbreaker was my dad's questionable taste in music.2 I like to think there's an alternate universe where they saw the movie, decided it appealed to them much more than The Paper Chase, and I had a very different childhood. But even if that's not how it would have played out, there's a shot in the movie that might have given them some perspective. It's of a corrugated fence on which someone has written:

DONT PISS U URINE

at this Gate

People are Living

here

Thank you

There are worse things in life than a blocked driveway, after all.

Randoms:

- The Harder They Come was nearly remade between 2003 and 2006 on three different occasions, with three different stories and three different stars. Sara Risher, one-time President of Production at New Line Cinema and now independent producer, brought the project to New Line. She was kind enough to sit down and talk with me about its various incarnations; together, they form a nice object lesson in the vagaries of the development process. Though she acknowledged that some of the qualities of the original would be difficult to reproduce, she made a convincing case that the basic outline of the story was timeless enough to be adaptable. The music industry certainly hasn't gotten any less rapacious since 1973. But because the original relies heavily on Jimmy Cliff's charisma, the main task was attaching someone who could carry the movie: an actor who could sing or a singer who could act. Three people were involved at various times:

Mos Def: This version was set in New York City and was to feature dancehall/hip-hop crossovers on the soundtrack. Bryan Goluboff wrote the script, which addressed some of the weaknesses of the original story. For one thing, Goluboff finessed the moment in Henzell's film where Ivan abruptly becomes a cop-killer. I also liked the last image, which would have used a police helicopter's spotlight to directly link Ivan's criminal career to show business. The film had a greenlight, but Mos Def dropped out to make 16 Blocks.

Today, New Line's option has lapsed and the rights have reverted to the Henzell estate (Perry Henzell, a friend of Risher's, died in late 2006). But Risher has the right of first refusal for any future remake, so she may still manage to get it to the screen.

Eve: Risher started from scratch, reimagining the project with a female protagonist. This would have been an interesting take, because Ivan's character is so driven by machismo. Kate Lanier wrote the script, and as before, it was greenlit. Then UPN unexpectedly picked up Eve's eponymous television show for another season, and that was that.

Lauryn Hill: Hill actually approached Sara Risher; she'd heard about the remake and had her own idea for the story. Hill's version was set back in Jamaica, but had an American tourist in the lead. Hill came with built-in reggae credibility; she has five children with Bob Marley's son Rohan. Risher went out to writers for a third time, but before a script was written, Lauren Hill went into seclusion and once again, things fell apart. - This was the first Jamaican film, and so it had a built-in and passionately loyal audience in its home country. It's hard to imagine belonging to a culture that had never seen itself on film, but that's the situation Jamaicans found themselves in in 1972. Perry Henzell reports on the commentary track that audiences were won over in the first sequence, one of those everyday occurances that had never made it to the big screen before. The bus Ivan is taking in to Kingston has a pointless faceoff with a truck on a one lane bridge.

- That shot apparently got audiences to erupt into cheers all over the third world.

- The preacher Basil Keane plays is pretty crazy, but he's got nothing on the real preacher at the church they shot at. There's some footage of him in the movie; a lot of yelling and a whole lot of banging his bible. I kind of wish they'd cast him.

- Beverly Anderson has a small role as a housewife; she went on to marry Michael Manley and become Jamaica's First Lady.

- She's way better than Nancy Reagan on "Diff'rent Strokes." Come to think of it, she's better than Ronald Reagan in Bedtime for Bonzo.

- Perry Hanzell got to make the first movie from Jamaica, an shortcut to critical importance that's no longer available to any of you. But don't despair! There are still countries with no local films. The IMDB lists 190 different countries where films have been produced; the CIA World Factbook lists 266. That leaves 76 countries just waiting for someone to put them up on the big screen. And even if we accept that Factbook regions like "Antarctica", "Clipperton Island," and "Holy See (Vatican City)" are unlikely to become the next Toronto, there's still a lot of potential there. Plus, if you're not from a country with no locally produced films, you might be from one of the ten countries with exactly one locally produced film.3 So if you're one of the 1,492 residents of Niue, the world is waiting for you to produce a followup to your country's first and only film.4 Or at least the Niueans are.

1Well, maybe not modern-day record moguls, but this was filmed before Napster.

2C.F. "Herman's Hermits Greatest Hits." On cassette.

3The ten countries with only one film on the IMDB are:

4Mella Lahina's Niue: This Is Your Land, which appears to have been a student project.

12 comments:

Since this seems to be one of your most research-intensive writeups yet, I want to know what Vigorton 2 was. (Only if you have any downtime in the near future.)

Jeff,

I was actually curious about Vigorton 2 myself, and had a note to look it up, but never did. So: It's a vitamin tonic, produced by the Federated Pharmaceutical Company and distributed by Lascelles Laboratories Limited, both Jamaican firms. It now has a more modern logo, which you can see here. Vigorton 1, or Vigorton "Classic" is no longer available, however. It's also a reggae song, by King Stitt. It sounds a little like something you might hear at a roller skating rink, though, and was probably the inspiration for Zombo.com, since basically the song is King Stitt chanting "Drink Vigorton 2! It's good for you!" over organ. Hope that clears things up!

Thank you. This post was great, and not just because I used to work in one of those office buildings next to your old place. [Harvard owns it now, I think. Harvard owns everything.]

I taught THTC last fall for a world film in American contexts class I designed in which I screened only Criterion DVDs. I included it for a buncha reasons: to make sure blacks were represented on the screen, and poverty, and this hemisphere. Also because its theatrical release helped mark the transition away from theatres like the Brattle to places like the Orson Welles and student film societies as the primary exhibitors of art house/cult flicks like this. I just wish I'd found that Crimson article you linked to!

And how boss is that shirt Cliff wears to record?

Cinetrix,

Glad you liked the essay, and it sounds like you taught a great course. What else did you show? And I've been looking for that shirt or a reasonable facsimile, but so far, no luck!

One of the scenes in this movie has Ivan being beaten as official punishment. His penis goes though a hole in the wooden apparatus he is strapped to and we literally see the piss being beaten out of him. I don't know of any other movie that has done anything similar. It was effective, too, not just for showing harshness and pain but also the humiliation that is part of Ivan's existence.

Oh word, you lived in that house? Crazy that it's still there. I lived (practically) in the Orson Welles, and the Brattle, and the H. Square.

The Orson Welles is where I made my movie-geek bones as a youngster, sneaking out my window to catch midnite shows. Remember the sign at the concessions counter? "Hot Budded Pupcon".

CCBC,

There's something on the commentary about that scene—apparently it was more explicit, but Roger Corman (really!) made Henzell cut it down. It's a great, economical series of shots the way it is, though.

Anonymous,

I didn't ever get to live in that house; I wasn't born until 1976. By then, my parents lived in Ohio, so I never had the pleasure of seeing a film at the Orson Welles. The only place to see good movies during my childhood was the student center at the University of Tennessee (I grew up in Knoxville), and then in college, Images Cinema in Williamstown. These days I'm all about the New Beverly in Los Angeles.

I loved this film actually... I know it's got terrible moments, but it has this rawness of a young country trying to capture a mood. Fantastic!

Enjoying your site. I just discovered it.

In 2005 I lived a block from where the Orson Welles had stood, and I have noted that yellow house many times.

Way back when, The Orson Welles was a formative part of my movie-addiction. Yet, I never saw "The Harder They Come" (that summer I was working in Cambridge). I saw tons of movies, but not "Harder". Guess I thought it might be too happy (based on the uptempo soundtrack which I did hear all the time). That's how I was then, always looking for existential gloom. Well, I still look for that, but your comments have made me want to finally see "Harder"

So thanks!

Jay M

I was fairly certain that "Beau Travail" was film in Djibouti, but I could be wrong or they left it off since it's first associated with France.

Ah WELL- yes I remember *THAT* house- but at the Wells we often cared about the masses more than the neighbors (to our chagrin).. like handing out free food (mostly comprised of our baker Melinka's wonderful Bread) out of the back door of the restaurant. After all these years- I can say we are sorry to have intruded... but you have to admit- those were some heady daze.

Post a Comment