Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962, written and directed by Agnès Varda.

Depending on how anal-retentive your English teachers were, you may have been given a handout at some point with a list titled TYPES OF CONFLICT. The one I got looked like this:

- Man Versus Himself

- Man Versus Man

- Man Versus Nature

- Man Versus Society

And so on. According to my seventh-grade Xerox, all conflicts in literature fit into one of these categories. Man Versus Himself is the list's sole example of internal conflict, and literature is full of it. But think quickly: what's the last film you saw where the only conflict was internal? My guess is you can't think of one. There are plenty of films where characters have internal conflicts, like the self-loathing mother and daughter in Autumn Sonata. But the action of these films, even the most introspective, tends to center around the way those conflicts play out when two or more characters are battling each other. There are films where a single character has a change in perspective that propels the story forward, but usually filmmakers go to great lengths to make these changes appear onscreen externally and visually. Think of Kevin Spacey's new car in American Beauty, or the entire character of Tyler Durden in Fight Club. Internal conflict isn't something that lends itself well to the medium of film. So when I tell you that the most important conflict in Cléo from 5 to 7 is entirely internal, you know we're talking about a pretty unique film. When I add that the internal conflict is not the kind of Freudian self-loathing and projection that movies thrive on, but rather Sartrean bad faith, we're into even more rarified cinematic territory. And when you find out that it's filmed in 24-style realtime, as though it were a thriller, well, there's nothing in that particular Venn diagram but Cléo from 5 to 7. So what was Agnès Varda thinking?

For one thing, she was thinking that there's more than one kind of ticking clock. The film opens with the sound of a literal clock ticking, as the film's main character draws the worst possible Tarot card:

The fortune teller gives her the usual bullshit about how the card represents change and transformation, despite being called DEATH and having a skeleton on it. Confirming my skepticism, the second Cléo has left, the fortune teller tells another man, "The cards spelled death, and I saw cancer. She is doomed." So if Varda chose to break the film down into minute-by-minute clockwatching, in which each chapter covers a very specific stretch of time, it's only because this is precisely where Cléo finds herself on her personal journey toward that Tarot card.

Cléo, played by Corinne Marchand, is a minor pop star, who has recorded a few singles but is far from established. She's cinema's closest thing to Sartre's bad faith waiter:

His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the consumer... All his behavior seems to us a game. He is playing, he is amusing himself. But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a café.

Cléo plays at a lot of things over the course of the film, but like anyone acting in bad faith, she's not very good at it. Watch the way she puts her hand on her chest in mock-humility when she admits to a taxi driver that she's the singer of the music that's come over the radio:

That's her best pop-star imitation, but she's just a little too over the top. For Sartre, bad faith is a way of denying agency and responsibility (being for-itself attempting to become being in-itself, to use his terms), and certainly this is part of what's going on with Cléo. But as you've noticed from the stills, she's a beautiful woman, which means that she has a somewhat more difficult struggle for authenticity than most, because people line up to offer beautiful women inauthentic roles to inhabit. Witness Cléo's encounter with her lover, one of the least subtle portrayals of mutual deception on film. Cléo plays her part to the hilt, wearing a frilly nightgown and greeting her lover on a rococo catastrophe of a bed.

Soaring romantic music plays during their conversation, despite the fact that the conversation is about the fact that neither of them has any time for other. Asked why Cléo should continue to see him, her maid offers a list that ends lamely with, "He knows everyone in Paris. You go well together. He's tall." Even Cléo's apartment is overtly theatrical:

Notice the separate sets with large empty spaces between; it's the way you would set up a stage to cross-cut between locations without scene-breaks. Although it's clear that everyone in Cléo's life offers her roles to play, it's equally obvious that she is quite happily complicit in her own deception. And as Cléo notes while shopping for hats, "Everything suits me. Trying things on intoxicates me." Varda underscores this point with a stunning tracking shot where Cléo nearly disappears in the store window's reflections. With this many surfaces, what hope does she have of finding depth?

Well, mortality cuts through surfaces pretty quickly, it turns out. In fact, this happens quite literally later in the film—we see a shattered shop window where someone smashed their head in a fatal car accident.

And Cléo has more on her mind than a Tarot card. She's waiting to hear the results of a medical test to determine whether or not she has cancer. At first, her main concern seems to be whether or not disease will make it harder for her to continue playing at life; on the way out of the fortune teller's, she thinks to herself, "Ugliness is a kind of death. As long as I'm beautiful, I'm alive." And virtually everyone in the first half of the movie encourages her in this sort of shallow narcissism. The worst offender is Bob, the pianist who is responsible for her career. He's played by Michel Legrand, the film's composer, and all his charm can't hide his contempt for Cléo as soon as she behaves as anything other than a vehicle for his own success:

The worst of it is, he's right about her limitations, and Cléo knows it. "Leave the songs, I'll choose later," she says, when throwing him out of her apartment. "But you can't read music," he reminds her. By the time she storms out, he's called her a "self-pitying, spoiled child" (pretty close to the truth, at that point), but as Cléo leaves, Varda adds a bit of set dressing to suggest he isn't much better:

If Cléo from 5 to 7 were made today, I'd expect there to be a huge moment of revelation, a point where Cléo (probably in tears), decides that she's been living the wrong kind of life and vows to change. The closest thing in the film is the scene where she throws a tantrum at her composer, but Varda shows this as just another instance of bad faith; at the end of her speech Cléo literally walks behind a curtain and her maid remarks, "What a performance!" So for a woman like Cléo, who is surrounded by people who enable her bad faith, is authenticity possible? Varda's answer would seem to be a tentative yes. But it's not easy.

So how does Cléo get there? Not a lot happens in the rest of the film: Cléo goes to a café, puts one of her own songs on the jukebox, and wanders around seeing how people react. The result is a great big nothing; people continue their own conversations. She hangs out with a friend who deals with the male gaze by confronting it head on:

Talking about modeling, her friend tells her, "My body makes me happy, not proud"; the polar opposite of Cléo's vanity. Cléo does have a moment of insight, thinking, "I thought everyone looked at me. I only look at myself. It wears me out." But it's internal, not a statement she makes to anyone. And that, Varda suggests, is how real change happens: anything Cléo articulates to others will be (or at least be seen as) a performance, just the inhabiting of another role. So in a sense, the very lack of big, dramatic moments of change in the film shows us that Cléo is genuinely approaching authenticity. It's no mistake that, shortly after this, Cléo sings to herself while wandering through the park. It's her most choreographed scene, and she's not performing for anyone:

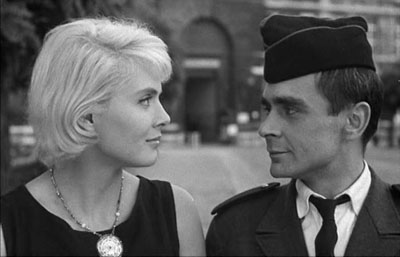

It's a little strange, because she's being very overtly theatrical here. But what matters is that no one is there; she's singing to amuse herself, not for an audience (except for us, but I don't want to go into that particular hall of mirrors right now). It's this change in her motives that makes the final scenes of the film possible, in which Cléo meets a soldier about to leave for Algiers, and makes a genuine human connection:

It's the happiest we see her. Some people criticize the film because of its ending: the relatively articulate feminist critique of Cléo's bad faith ends with her meeting a man. But I think this misreads the film's structure. The real climax of the film is Cléo's realization that she's wasting her energy inhabiting roles. The scenes with the soldier are more like an extended denouement: the film wouldn't be appreciably different if she met a woman in the end. The final shot is not a kiss between the two; it doesn't seem to be a particularly sexual moment at all:

I've read comparisons here to the ending of The Graduate, but I think that misses the tone. What I saw in the last frames of Cléo from 5 to 7 was not awkwardness, but connection: Cléo presenting herself to someone for the first time without artifice or caprice. Avoiding bad faith is a constant struggle for anyone (and a particularly difficult one for women, since men tend to define their own agency by denying it to women). Cléo manages it for a moment, at around 6:30 PM CET on June 21, 1961. It's enough.

Randoms:

- Michel Legrand went on to win three Academy Awards for his work as a composer. That's three more than Agnès Varda and Corinne Marchand combined. This gives a little more bite to Cléo's complaint that he undervalues her talent.

- Cléo from 5 to 7 is 90 minutes long, and it really is in realtime. The first time I saw it, I imagined that the two hours had been compressed. But in fact, the film ends at 6:30, and the time in the chapter headings really does match the time elapsed in the film. Eric Henderson offers an interesting but pessimistic interpretation for the missing half-hour here:

...the film comes to an abrupt and unadorned halt following the revelation that Cléo's condition is not life threatening, suggesting that she lives life from crisis to crisis... Cléo is a non-entity when she's not making a scene. When the film's impetus is removed, Cléo simply ceases to be, cinematically speaking.

- The film's camerawork is top notch. It's overwhelmingly handheld, and the outdoor shots in Paris feel like Varda just let her actors wander around the streets. Which I imagine is exactly what happened; I find it difficult to believe something like this is a staged shot:

- Varda began her career as a photojournalist, and this shows in the realistic way she captures Parisian streets. Unfortunately, the verité feel is somewhat undercut by the obviously non-production sound and heavy-handed foley work. The images themselves are spectacular, however. I particularly liked a long tracking shot that follows Cléo and Dorothée's car for a full city block from what would appear to be a balcony:

- I can be precise about the time because of the chapter headings, the date because of a radio broadcast that mentions it, and the year because the same radio announcer talks about the Kennedy-Khrushchev meeting in Vienna that happened earlier that month. For what it's worth, it was a Wednesday. So put June 21, 1961 up there with June 16, 1904.

- You've probably noticed that the opening shots of the film are in color; apparently they were not always presented that way, since the Criterion Collection says that these were "restored." I'm not sure why Varda used color for this sequence. Shock Corridor also had a color sequence in an otherwise black and white film, but Fuller used this in a dream sequence, where it had an obvious purpose.

- Watch for a who's-who of New Wave during the film-within-a-film. Varda got Jean-Luc Goddard, Anna Karina, and Eddie Constantine to appear in the pastiche of silent comedies that Cléo watches. Here's Goddard doing his best Harold Lloyd:

- I know, I know, a review of a feminist movie ending with a man. But if it was good enough for Varda, it's good enough for me.

9 comments:

Great posts, as always. You showed me how much I had missed when I last watched the film (I'm kicking myself I didn't notice the little boy tapping away on the toy piano!), and your comments about Cleo playing at behaviours as well as the quote from the Slant review, clarified a lot for me!

Colinr,

Thanks, and thanks for the link from the Criterion forum, as always. The Slant review gave me the same effect mine apparently did for you; I was kicking myself for not thinking about the missing half hour more rigorously. And yeah, I love that toddler with the piano -- there's no credible reason at all he'd be there!

All right I'll bite, what happened on June 16, 1904?

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan, &c..

Haven't seen this yet, and after reading your analysis I'm really looking forward to it.

I'm wondering if you've seen Godard's film Vivre sa vie, or My Life to Live in English. It seems to have some similar themes of acting out roles and inauthenticity, although I can't make any good comparisons since I haven't seen Cleo from 5 to 7. It's out of print in the US, and I've heard some rumblings of a Criterion release, but nothing concrete.

I haven't; I'd be interested in knowing your thoughts once you see Cleo.

I just stopped about 2/3 of the way thru watching Cleo to read your thoughts about it. I don't have a version with English subtitles, so I'm trying to catch a little more of the French with each viewing.

A couple of things I've noticed: Near the beginning of the film as she and her companion leave the cafe, they pass a shop with a sign that says "DEUIL" (mourning; presumably black clothes) - Cleo then proceeds to buy a black fur-trimmed hat. Later, after she leaves her apartment in a huff, wearing basic black, she passes a shop called "Bon Sante" (good health). Shortly after, she passes what looks like a long procession of people - there's no coffin, but it may be a funeral procession. Life / death / life /death.

"she's a beautiful woman, which means that she has a somewhat more difficult struggle for authenticity than most, because people line up to offer beautiful women inauthentic roles to inhabit."

Excellent and insightful analysis. Really appreciate your thoroughness, curiousness, and optimism as a film critic. Glad to have found you. :)

I couldn't find this anywhere on the internet so I decided to create it myself. For those of you who are curious, here they are....

CHAPTER TITLE CARDS from Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) by Agnès Varda

The numbers in italics below are the actual running time start of each title card, give or take a second. Note that I zeroed to the first frame of the tarot card reader scene, not the first chapter title card. –Su Friedrich

Chapter 1: Cléo from 17:00 to 17:08 (leaves tarot reader, walks to café)

(4:43 to 7:35)

Chapter 2: Angèle from 17:08 to 17:13 (freaks out in café, Angele tells story, lovers quarrel, goes to hat shop)

(7:35 to 12:34)

Chapter 3: Cléo from 17:13 to 17:18 (still in hat shop, taxi with woman driver, African masks)

(12:34 to 18:03)

Chapter 4: Angèle from 17:18 to 17:25 (continue taxi, into her apartment, cleaning up, changing)

(18:03 to 25:03)

Chapter 5: Cléo from 17:25 to 17:31 (lover visits her, then C & A talk about him and illness) (25:03 to 30:46)

Chapter 6: Bob from 17:31 to 17:38 (the musicians arrive, tease her, start to play and sing)

(30:46 to 36:57)

Chapter 7: Cléo from 17:38 to 17:45 (sings the sad song; wig off, black dress and hat on, the man with frogs)

(36:57 to 43:52)

Chapter 8: Some others from 17:45 to 17:52 (to her old café, lots of overheard conversations, then people on street, esp. older women, and flashbacks)

(43:52 to 51:00)

Chapter 9: Dorothée from 17:52 to 18:00 (the sculptor’s model, driving, tells her about cancer, counts pompoms)

(51:00 to 58:31)

Chapter 10: Raoul from 18:00 to 18:04 (the silent movie)

(58:31 to 1:02:36)

Chapter 11: Cléo from 18:04 to 18:12 (broken mirror, man killed, taxi to the park, meets Antoine)

(1:02:36 to 1:11:17)

Chapter 12: Antoine from 18:12 to 18:15 (he apologizes, she asks the time, “I don’t know. Six or six-fifteen.”, they walk and talk, cancer, being killed in battle)

(1:11:17 to 1:14:49)

Chapter 13: Cléo and Antoine from 18:15 to 18:30 (the bus, the hospital)

(1:14:49 to 1:29:11)

Post a Comment