Vagabond, 1985, written and directed by Agnès Varda.

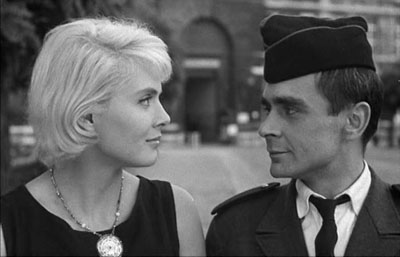

In Cléo from 5 to 7, Agnès Varda made frequent use of tracking shots to follow Cléo along Parisian streets, and she does a lot of the same kind of camerawork in Vagabond. But while the narcissistic Cléo is nearly always in the center of the frame, Vagabond's protagonist, a homeless young woman named Mona Bergeron, can barely stay in the picture. Again and again, she either walks into the frame of an already-in-motion tracking shot, or falls behind, or walks out of frame as the camera keeps moving. It's as though she is on the periphery of her own movie. So it's strange that the film's cinematic predecessor is none other than Citizen Kane. Say what you will about Kane, he's never framed as an outsider:

Vagabond's link to Citizen Kane isn't immediately apparent. If you watched only the first two minutes of the film, you'd think it was an ancestor of CSI. Varda opens with the discovery of a frozen corpse in a field:

The melancholy violin music and long, slow zoom over a winter field lets us know we're not in a police procedural, however. After briefly showing us the police investigating the body, Varda explains via a voiceover that after talking to people who met Mona towards the end, she is going to tell us "a tale of the last weeks of her last winter." Like Citizen Kane, this is a story that pieces together other peoples' impressions in an attempt to give a coherent picture of someone's life (or at least the end of it). But if you remember Cléo from 5 to 7 (or Citizen Kane, for that matter) you'll remember how easily people project their own desires on those they meet. So we can't expect reliable narrators; throughout the film, we'll be given head-on interviews with people who met Mona, telling us what they thought of her. More often than not, their versions will obviously reflect their own fears and desires, not anything we actually see of Mona herself. And even Varda as narrator obviously romanticizes Mona: she ends her narration by telling us that "it seems to me she came from the sea." This is followed by a shot of Mona walking ashore like Botticelli's Venus:

From this idyllic opening, we trace Mona's decline to the point we first meet her, dead in a ditch. Most films about outcasts subscribe to something like the Great Man theory of history. Think of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, or even Nights of Cabiria. These movies are about outsized personalities, unique individuals who chafe against the world around them and follow their own paths, whether this is Randle Patrick McMurphy's doomed rebellion or Cabiria's unjustifiable optimism. Even Cléo from 5 to 7 works this way (though Cléo is hardly an outcast). Vagabond is a little different: Mona is one of the most passive protagonists you'll ever see, an empty space at the film's center that the other characters project themselves onto. There's an establishing shot in the film that expresses this nicely:

Varda spends next to no time asking questions about how or why Mona ended up homeless (the primary concern of most films about people on the skids). We learn that she went to vocational school, knows a little English, and once trained as a typist, but these details take up less than thirty seconds of screen time. When we see her alone, the filmmakers are almost always focusing on the gritty logistical details of life on the road. And I do mean gritty; Mona is filthy, and this is one of the few films you'll see where other characters consistently complain about how terrible the protagonist smells:

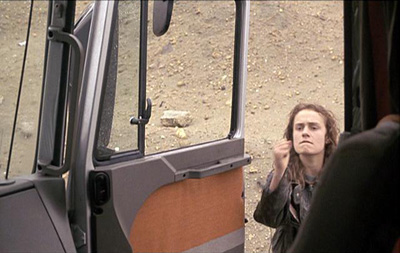

This isn't a glamourous portrait of life as a vagabond. For the most part, Mona (memorably played by Sandrine Bonnaire) seems pretty miserable, whether she's trying to eat a baguette that has frozen solid or flipping off a truck driver who propositioned her.

Throughout the film, Varda gives us more information about Mona than the other characters have. As a result, we are able to evaluate their judgments about her in ways they are not. Most are wildly inaccurate, but pride of place goes to a maid named Yolande, who meets Mona twice during her descent:

Yolande first sees Mona when she is crashing out in an abandoned mansion with another vagabond:

Given the circumstances in which Yolande sees Mona, her impression is understandable (if the psychology behind it is heartbreaking). She tells the camera that she wishes Paulo, her loutish boyfriend, "would dream with me like the lovers in the château, in each other's arms." From our privileged position in the audience we get to see that Mona is actually just hanging out with the guy in question until his drugs run out, and when he's attacked by burglars, she does nothing to help him. But just as we're patting ourselves on the back, Varda makes it clear we don't know Mona as well as we thought. Mona meets an aging hippie and his family, who are eking out a living by raising goats:

It's not much of a life, but it's a way of surviving while checking out of the world of offices Mona speaks so contemptuously of. When Mona casually says that she'd like to have a little plot of land to grow food on, the hippie gives her exactly what she's asked for, plus a trailer of her own to live in. By way of thanking him, Mona sits in the trailer all day smoking cigarettes until the exasperated family finally evicts her. "You live in filth like me, you just work harder," she tells the man on her way out the door. She's right, but this isn't the kind of noble rebellion movies have coached us to expect in this kind of situation. Instead, Mona is willfully stubborn and self-destructive. As the hippie puts it, "That's not wandering, that's withering."

In the end, withering is what Vagabond shows best. Mona's tenuous grip on what little she has begins to loosen about halfway through the film, when she discovers that a painting she's got in her backpack has a hole punched through it:

From this point on, Mona, at least, seems to know where her story is headed. You can hear her fear in the way she yells about the painting (which she immediately throws into the fire). What's shocking is how quickly her situation deteriorates towards the film's end. I think one of the film's greatest strengths is the way Varda captures how quickly the luck of someone in as tenuous a position as Mona's can run out. It takes about five minutes of screentime for Mona to go from being in control of her own situation to nodding out in a train station with a fine specimen of Eurotrash who is trying convince her to appear in porn:

The really brilliant thing about Vagabond is the way Varda has several other characters fall apart simultaneously. Consider Lydie, the only character Mona ever seemed to have much fun with:

Mona and Lydie share a bottle of cognac and really hit it off (and Lydie is hilarious). But just about the time Mona's really getting into drugs, Lydie is getting trucked off to a nursing home by her greedy nephew and his wife, the closest thing Vagabond has to villains:

The two also get Yolande fired and sent to another city, without her boyfriend. It's a structural cheat, but it's surprisingly effective. The general impression the last twenty minutes of the movie gives you is of everything collapsing on itself shockingly fast. These last scenes, more than anything else, give Vagabond its emotional power. At the film's end, I was left wondering how secure my own grip on my life was. Any film about a homeless person asks the audience this question, but usually the message is that we shouldn't give up on those on the outskirts of society. I can think of no other film that suggests so relentlessly that our best efforts keep us, at best, a few bad breaks from being found dead in a ditch or left to rot in an old age home, mourned by no one. Vagabond's message isn't "There but for the grace of God," it's something simpler: "There."

Randoms:

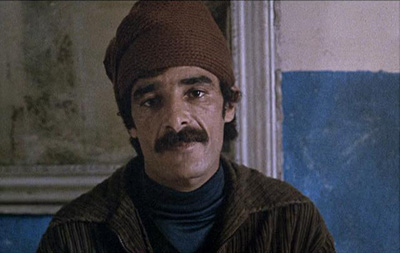

- It would take another essay to talk about the differences in what Mona meant to the different characters in the film, but it breaks down into two basic camps. Men tend to describe her dismissively, and in a disappointed fashion. Women assume she has whatever qualities they are afraid they are missing themselves: freedom, love, friendship. The only people who don't offer any assesment of her after the fact are the ones who seem to have actually gotten to know her. We never hear from Lydie after she is taken to the nursing home, but we do get an interview with Yahiaoui Assouna, a man who taught her to tend vinyards, and seemed to be the only character who got her to think of any kind of a future ("I'm learning my trade," she says when he points out her blisters after her first day at work.) Significantly, he's the only person who doesn't say anything about her in his interview, just looks silently at the camera before clutching a scarf she left behind to his face. His eyes are hard to meet:

- The film never lets us get close enough to Mona to learn why she's so damaged. But it's painful to see her occasionally reach out for affection, always from people who won't reject her. While working at the goat farm, she tries to caress the cheek of the farmers' daughter when no one is near:

- And earlier, she tries to connect with someone even less likely to make her suffer rejection:

- Yolande and Paulo's room has the most pop culture references per square inch (pcr/in2) of any set in film history.

- In one room, that's a David Bowie poster, a Prince poster, an unidentified picture of another singer I can't identify, and a Rolling Stones t-shirt. It's their own virtual version of Live Aid.

- The best snarky review of the film comes from The 16mm Shrine. It's short and to the point:

A homeless French woman drinks a great deal of wine and dies in a field. Exactly as exciting as it sounds. ... Cue rapid montage of ABSOLUTELY NOTHING HAPPENING.

The full review is here.