Testament of Orpheus, 1959, written and directed by Jean Cocteau.

Like most lovers of cinema, my response to Testament of Orpheus is constrained by the way I reacted to Armageddon. At the time, I wrote that it didn't make sense to judge Michael Bay and Andrei Tarkovsky by the same standards, since their goals had so little in common. My reference for that point was David Foster Wallace's essay about David Lynch, in which he sets up the familiar art film/studio film dichotomy in order to argue that Lynch's work falls into a third category. As far as I know, Lynch isn't on the record about this.1 But Cocteau is, and to say he finds traditional methods of understanding film inadequate for his work is something of an understatement. Here are his thoughts about symbolism:

When a Frenchman no longer understands he never asks himself if it is necessary to understand—he either gets angry or he takes refuge in symbols. "I don't understand, therefore it must be a symbol," is a typically French way of thinking. "Either what I’m seeing doesn’t mean anything, or else it means something different from what I am seeing, and that something different may be hiding a symbolic meaning."

And here he is on narrative in cinema:

[C]ineasts [are] harassed by producers who think that they know the audience and have never outgrown the childish desire to be told a story, demand a "subject" and an excuse, when the manner of saying and showing things, and furnishing the screen, are a thousand times more important than the story you tell.

And finally, definitively, here's Cocteau about that whole Enlightenment project of trying to understand the world around you:

"[T]he French people [have a] frightful mania for understanding everything. Why? This is the leitmotiv of France: "Explain what you were trying to paint." We are only a step away from having to explain what music means: as in the Pastoral Symphony, where the auditorium is delighted when it can recognize the cuckoo and the peasant dances.

In fact, everything that can be explained or demonstrated is vulgar. It really is a time that mankind admitted that it is living on an incomprehensible planet...

Well, all right then. In the framework Cocteau wants his films to be evaluated in, looking for meaning or narrative makes you vulgar, childish, or a Frenchman. That puts paid to my feelings about The Blood of a Poet. I'm not certain a filmmaker can magically create a world in which exegesis is superfluous simply by writing "SANCTUARY" on his film canisters. But if any film were going to destroy a critic's reliance on meaning, narrative, or symbolism, it would surely be Testament of Orpheus.

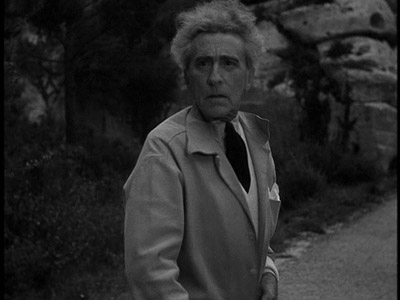

Unlike Cocteau's other stabs at the Orphic myth, this one stars Cocteau himself:

As Cocteau warns, it doesn't make any sense to describe this movie in terms of narrative. It's more like a dream; some sequences have their own internal logic, some don't. The whole proceedings are haunted by Orpheus; the film actually opens with the final scene of the earlier movie. Later, Cocteau is put on trial by the characters of the Princess and Heurtebise from Orpheus, with María Casares and François Périer reprising their roles.

Edouard Dermithe also reappears as Cégeste, first as a photograph that appears from a fire thanks to Cocteau's favorite reversed-film trick:

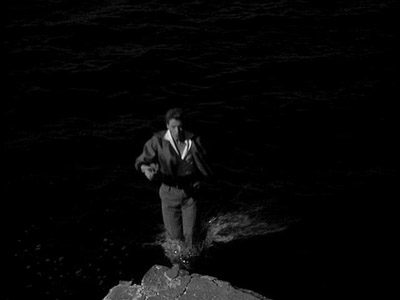

And then rising magically from the ocean thanks to the same special effect:

In fact, the film is kind of a highlight-reel of Cocteau's favorite special effects. He gives himself the old painted-eyelid treatment:

And then does the same to Jean Marais, casting him as Oedipus and replacing the staring eyes he usually paints with bleeding sockets:

Throughout, Cocteau defiantly avoids narrative structure. The closest analogue I can think of is Nietzsche's aphoristic works. Characters are constantly spouting off things like "works of art create themselves and dream of killing their creators," and "an artist always paints his own portrait." This frees Cocteau to put visual jokes anywhere he wants. The best one is this couple, taking notes after each embrace:

Intellectuals in love," Cégeste solemnly tells Cocteau.

Testament of Orpheus has as many famous cameos as reversed-film effects. Picasso shows up for no apparent reason, watching Cocteau's funeral from a balcony:

And Yul Brynner, of all people, appears as a bored functionary who owes more than a little to the gatekeeper in Kafka's "Before the Law:"

Going on the record about this film is a sucker's game, at least if you play by Cocteau's rules. But since this site already pretty clearly establishes me as a sucker, or at least someone who likes both meaning and narrative, I doubt this will do too much damage to my reputation. So: some of it was amusing, some of it was interesting, some of it was silly, some of it was dull. None of it had much unity of purpose that I could see, except as a trap for critics. Here's one more quote from Cocteau:

The Testament of Orpheus is simply a machine for creating meanings. The film offers the viewer hieroglyphics that he can interpret as he pleases so as to quench his inquisitive thirst for Cartesianism.

(I have said in The Potomak that if a housewife were given a literary work of art to rearrange, the end result would be a dictionary).

Now that sounds remarkably teleological, and kind of ingenious. The frustration Cocteau's non-narrative films cause in viewers stems from the viewers' Cartesian over-reliance on reason. If you read them this way, the films are meant to provoke a crisis, an area where reason cannot penetrate, pushing viewers forcibly toward Pascal. Or at least toward the Chapman brothers. If that's the goal, however, one must note that Orpheus does this more effectively than either of the non-narrative films.2 I believe our desire for understanding is inextricably linked with our "childish" interest in narrative. So if you want to trap the one, you would do well to enlist the other.

The most frustrating thing about Cocteau is that he must have known that Orpheus was a better film than The Blood of a Poet. He wrote about Orpheus like it was a sop to unsophisticated audiences. But in Testament of Orpheus, explicitly conceived as a return to his first film's sensibility, he keeps bringing back images from Orpheus, not The Blood of a Poet. Even if one accepts Cocteau's premise, the swipe at housewives casts doubt on his motives. One must oppose the Enlightenment not because it is inadequate, but because it is bourgeois.3

Cocteau died before Barthes published "Death of the Author," but they seem to share the idea that the ultimate interpretation of the work rested entirely with the reader. For Barthes, this was a way of liberating criticism from the limits of its creator's ideas and historical context. For Cocteau, however, the author's death (or the Poet's death, to return at last to the Orphic myth), is more like the ultimate blank check. If a work of art seems prosaic, unstructured, or dull to a viewer, chalk it up to the viewer's childishness, vulgarity, and housewifeliness. The Poet has nothing to do with it.

Randoms:

- The DVD features La Villa Santo Sospir, a 16mm film Cocteau made about Francine Weisweiller's villa, which Cocteau painted between 1950 and 1952. The film is mostly a recording of his frescoes and paintings on the walls of the villa (Picasso, another guest there, also painted some of it). The paintings on the doors are the same as the ones in the opening credits of Orpheus, although I'm not certain whether the doors are copies of the film or vice versa. I liked these double doors a lot:

- Cocteau also photographed a number of his oil paintings for this film. My favorite was this one, of Christ's temptation:

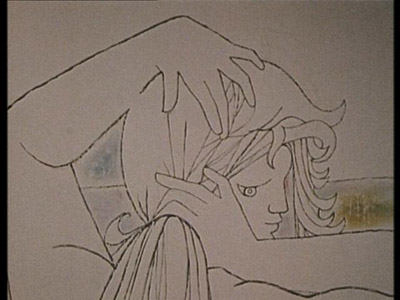

- Those two stills from Santo Sospir are misleading, because most of Cocteau's work there is closer to line drawing. Here's his version of one of Renoir's bathers:

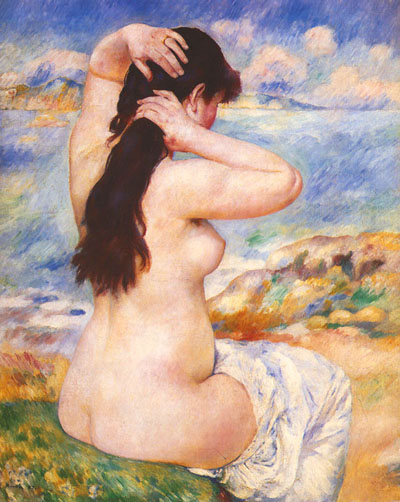

- And here's the original, which you'll find down the street from my alma mater at the only art museum founded out of fear of a nuclear holocaust.

- Cocteau did have a second goal in making Testament of Orpheus—He wanted the film to be an opening salvo in the battle to bring an end to the tyranny of narrative, for-profit filmmaking; to:

destroy these ridiculous taboos and educate the cinema audience, just as the public has been educated for art exhibitions.

That's an honorable goal, but not exactly how it played out. Narrative films pretty much won that war (in part, I think, because the great filmmakers of the seventies were all making narrative features). The last non-narrative feature that I can remember getting an audience was Matthew Barney's Cremaster Cycle. Which, probably revealingly, I haven't seen. I have always loved Man With A Movie Camera, but that's probably the most rational non-narrative film there is.

...

We shall not succeed overnight. But I shall be proud if my efforts contribute in some way and if, at some future time, young people are indebted to me for a little of their power to bring out a film as a poet publishes a book of poems, without being subject to the American imperatives of the bestseller.

2Idea for a film thesis: The best film version of Pensées is Alien. In France, the posters should have read "Le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis m'effraie."

3I think there's a trace of similar snobbery to be found in all the cameos, at least when combined with Cocteau's repeated insistence that everyone who appears is a good friend and is only in the film as a personal favor.

4 comments:

I love this review, Matthew, mostly because of the time you dedicated to research so that the reader could have a better understanding of Cocteau.

I have immense respect for nearly all filmmakers, even Cocteau, but from the way he speaks and the way he seems to hate narrative seems almost full of conceit.

I always feel that if something is done a certain way, in art at least, it should be done for a reason. Now I'm not saying this is law, but if you paint the sky blue, you should know why, just as well you should know why a character is named Horace and is a male.

It may seem almost arbitrary, but a work of cinema, or literature, or visual art should have purpose because I believe it creates within the work a more compelling power and a greater artistic quality.

It seems, at least from my (quite possibly incorrect) reading of your review, Cocteau holds an interest in only the visual, a negative claim that was constantly held against Stanley Kubrick.

By the way, there are a league of non-narrative films that function without characters, dialogue, or story. It's interesting that Cocteau thinks of himself as a bit of a revolutionary in his technique when even he has not gone to the greatest extent of the non-narrative film.

Though technically they begin with the film "Microcosmos," Godfrey Reggio's "Koyaanisqatsi" served as a seed for two sequels, "Powaqqatsi" and "Naqoyqatsi" as well as Ron Fricke's "Baracka" and "Samsara."

Now for the most out of place homage I've seen in quite some time:

Moe's Southwest Grill (a sort of Mexican fast-food restaurant) has as one of it's choice of Quesadillas, the "John Coctostan", further detailed as "Choice of protein, beans, shredded cheese, with a side of salsa and sour cream."

Other entrees include the "Alfredo Garcia" fajita and a "Close Talker" salad.

Anyhow, much respect to the French master, of course. We must respect our elders. Hehe.

Anonymous,

Glad you liked the review, but don't give me too much credit for research—the essay I quote is on the DVD. If you thought I was saying he was purely visual, though, my essay isn't as clear as I wanted—Cocteau seems too verbal to make something like Koyaanisqatsi. I'm not exactly sure what you mean by "purpose," but if you mean unity of form and structure then I agree. I think non-narrative films like the ones you mention have that.

That's great about Moe's Southwest grill. I looked them up -- they're changing all the names on their menu, so you won't be able to order a John Coctostan for long. The name may be originally a reference to Cocteau, by the way, but Moe's got it from Fletch. The strangest thing on their menu (and perhaps why they're changing it), though, is the "I Said Posse," which isn't exactly what you'd expect on a chain restaurant menu if you know the joke.

On another note, I finally saw After Hours tonight, which means I've seen two movies in a row with references to "Before the Law." I'm guessing that's the world record, but can anyone think of any others?

For movie references to "Before the Law," would Orson Welles' version of The Trial be cheating? I love the way he retells it in a film using projected slides of drawings--how contrary!

C.K. Dexter,

I've never seen it, but I'll count it. Touching on something we were talking about earlier, I was recently disappointed to discover that Orson Welles's version of The Stranger was unrelated to Camus.

Post a Comment