Charade, 1963, directed by Stanley Donen, screenplay by Peter Stone, story by Peter Stone and Mark Behm.

Studios and critics have alternated between celebrating and excoriating the Hollywood star system since Florence Lawrence first got her name in lights. For the purposes of this blog, I'm going to ignore the economic considerations of casting a star. This is really the only part of the whole thing that matters to studios, of course: casting someone who can open a movie is more important than finding a director or a script. As with everything else in Hollywood, the star system is all about mental real estate, shortcuts for the marketing department and so on. (And the only non-actor the unwashed masses remember is Steven Spielberg). But assume the battle is already won: the marketing department has ushered you at gunpoint to your seat and you're watching a movie with a star. When they appear on screen, whether it's Humphrey Bogart or Jim Carrey, you're seeing an amalgamation of the role that they're playing and their carefully designed persona. Don't get me started on the way stars protect their images to the detriment of playing interesting characters (see the differences between Skjoldbjærg and Nolan's versions of Insomnia for a vivid example). But sometimes filmmakers beat the system; if you know what you're doing, manipulating stars' images can be at least as interesting as debating whether or not Carrey or Cruise are worth 20 million.

Nobody understood this better than Alfred Hitchcock, who made some of the smartest casting decisions of any filmmaker. He's able to make Cary Grant an absolute bastard to Ingrid Bergman without losing our sympathy in Notorious because, well, he's Cary Grant. Jimmy Stewart's creepiness is a surprise every time in Vertigo, and although Anthony Perkins doesn't strike anyone as a young romantic lead anymore, that was his image until Hitchcock smashed it in Psycho. Shrewd manipulation of audience expectations of stars is one thing, and it's well represented throughout the Criterion Collection. But it wouldn't work at all if not for the vast body of movies that trade in on stars' personas without challenging them. That's where Charade fits in. Charade isn't a movie where stars play against type or where their personas are deconstructed. Rather, it's a giddy exercise in what William Goldman would call "stars as audiences want to see them." Appropriately enough, it looks a lot like a Hitchcock movie.

Like The 39 Steps, this movie is a mixture of thriller and romantic comedy. Stanley Donen was fortunate enough to get two of the most beautiful and beloved actors of their respective generations to play the romantic leads. Here they steal a moment together in the midst of chaos for a romantic meal:

As you can see, from the first frame, audiences wonder only one thing: how will these two lovebirds end up together? Ok, I apologize; that was ridiculous. Here's the real still:

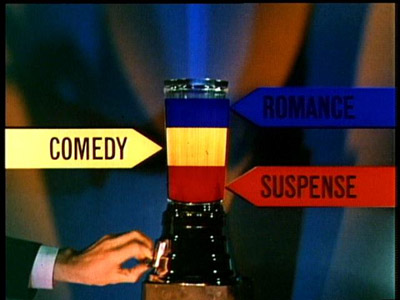

With Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn on screen together, you don't really have to do too much to make a great movie, or at least a fun one. Donen has a serviceable plot, with more than the required number of turnarounds. Hepburn, unhappily married, returns home to find her husband was not the man he claimed to be. Furthermore, she discovers he has sold all her possessions and gotten himself killed while fleeing France by train. It seems that the couple's wealth (a) was stolen from the United States government as part of a World War II pact and (b) has disappeared completely. This puts Hepburn in kind of an awkward position, since the other people who helped her husband steal the money are convinced that she has it. Fortunately, Cary Grant shows up out of virtually nowhere to help her outwit her husband's former army buddies. And when it comes to outwitting, nobody was ever better than Grant. Although Hepburn hadn't played the kind of character she plays in this movie before, anyone who's seen Wait Until Dark knows she can do one hell of a resourceful-in-a-crisis damsel in distress. One can imagine making this movie and having both actors play against type. But I don't want to see that hypothetical movie as much as I want to see the two of them being funny and charming. Basically being, you know, Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn. Charade is an ideal star vehicle for these two, drawing heavily from Hitchcock's movies (all the way back to The 39 Steps, as Charles Taylor has noted) for its particular mixture of genres. The trailer memorably categorizes Charade as something crafted in a blender:

The slight craziness of that image gives you a pretty good sense of the tone of the film. Donen was the director of Singin' in the Rain, which to me was always the best example of a film that works because of sheer over-the-top commitment. When Donald O'Connor starts singing "Make 'Em Laugh," it's not that funny. But nobody in the history of the human race has made it through the backflips that end that sequence without laughing; he's just so damn earnest about the whole thing. There's at least one sequence in Charade that has the same earnest goofiness, a bizarre set piece where Cary Grant takes a shower fully clothed.

It's not much of a gag but he sells it as wholeheartedly as Donald O'Connor (and I think there's an echo of Singin' In The Rain's raincoats in that Technicolor shower curtain). In fact, the scene could be lifted and set right in the middle of Singin' in the Rain and nobody would notice. But I invite you to find a place in Singin' in the Rain for the pre-credit shot in which we're introduced to Hepburn's husband:

The surprised expression and lacerations seem too grim for a Hitchcock movie. In fact, the violence in Charade is not really of a piece with the rest of the film, as early viewers noted. Bowsley Crowther's original review in the Times devotes five of nine paragraphs to warning about how sudden and grisly the violence in the film is (at times, he sounds as though he doesn't think his readers believe he's telling the truth: "I tell you, this lighthearted picture is full of such gruesome violence.") But although they seem at times to be from a different movie, for the most part, these scenes and sequences stand on their own as sick, funny set pieces. The highlight is Hepburn's husband's funeral: no one but the detective investigating his murder is there at first. But one by one, his army buddies show up, each trying in less and less subtle ways to verify that he is really dead. Here's James Coburn holding a mirror under his nose to see if it frosts:

This scene is a masterpiece of black humor and economy. Economy because it's your introduction to the villains of the movie, and roughly lets you rank their level of threat based on their behavior at the funeral. Black humor cause, well, you know, it's a funeral. The last to enter is George Kennedy, looking approximately ten feet tall:

I love the expression on James Coburn's face—when even Coburn is unnerved, you know you're in trouble. Kennedy doesn't even sit down—just slams the door open, stalks to the front of the room, jabs a hatpin in the corpse's hand, verifies that he doesn't flinch, and stalks right back out. No respect for the dead, that man; not one to trust. But then the movie doesn't have much respect for the dead either: the other steady progression through the film is the increasingly Byzantine ways the villains are killed. Here, for example, is how James Coburn's body is discovered:

As someone who has always thought the "do not put a plastic bag on your baby's head, or your own, especially if you're planning on choking yourself" icons were hilarious, I wholeheartedly approve of this shot. (For reference only:

See? Hilarious!) It's not for nothing Charles Taylor compared the murders in this play with the illustrations in a Charles Addams book. And in fact, the murders are shown almost exclusively in static shots; you see the bodies but not the deaths themselves. This lends the whole proceeding a sort of ironic detachment; the corpses are punchlines.

Grant and Hepburn pick up on this tone—Taylor called their performances "high deadpan," which seems about right. They deliver impossible lines in a very stylized way, and your reaction to it will depend on whether or not you enjoy Grant and Hepburn's screen persona in other movies. Of course, it's difficult to imagine reading most of Peter Stone's script in any tone other than arch detachment—the dialogue has little to do with what actual people would say in the situations Grant and Hepburn find themselves. To pick just one example, Hepburn tells Walter Matthau's CIA agent, "Mr. Bartholomew, if you're trying to frighten me..." with an unphaseable expression, then changes to a scared rabbit look to finish the sentence, "you're doing a first-rate job!" I'd tip my hat to any actor who can give that line a method reading, but I wouldn't hire them for this film.

Charade is much more playful than Hitchcock's thriller-romances, at least in the lead actors' performances. Presumably the genre conventions were laid down well enough by 1963 for audiences to respond to a movie this self-aware. But while the movie feels breezily ahead of its time in many regards, Hepburn and Grant's romance seems to be taken from a 1930's romantic comedy, not a film from the sixties—or even the fifties or forties, as a comparison to North By Northwest or Notorious will quickly show). Partly this was because of Grant's fear that he would look ridiculous pursuing someone Hepburn's age; he required that their scenes be rewritten so that she pursues him exclusively. The problem is, one of the major engines of the plot is whether Grant is a threat to Hepburn. It's hard to give him the requisite air of sexual menace when he doesn't kiss Hepburn back, and then says, "Oh, no. The doctor said it was bad for my... thermostat." Suddenly we're back in Bringing Up Baby mode, which is fair enough, but pretty clearly separates Grant from the other villains. One thing about George Kennedy's character I didn't mention by way of illustration: he's missing an arm, and has a habit of attacking people with his prosthesis:

Yes, that's as much of a joke as Grant's thermostat line, but Kennedy's missing hand is a sick joke (and one it's fun to imagine trying to get into a major studio movie today), and the tones don't entirely gel.

But who really cares if Charade is a masterpiece where every frame comes together to create a perfect, unified whole? It's got Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn, being charming, arch, and good looking. I love movies where the director carefully subverts a star's image as much as the next guy. But if you're going to appreciate that, it seems to me that you should also have some appreciation for the movies that cash in on that image in a relatively unironic fashion. Or to put it another way:

Randoms:

- The commentary track, with Peter Stone and Stanley Donen, is crawling with arguments. It was hard to tell whether Stone and Donen were just being crotchety or genuinely have some bad blood between them. Whichever it is, Stone hardly says anything that Donen doesn't contradict, even when it profits neither of them to argue. The best is a two minute fight over whether the French equivalent of Punch & Judy shows is called Guignol or Guignolet. Donen thinks it's Guignolet, Stone is of the Guignol camp. The confusion comes from the Théâtre du Vrai Guignolet:

- The name of the theater nonwithstanding, Stone is right and Donen is wrong.

- It wasn't entirely fair of me to choose Grant's "thermostat" line as an example of his tone being out of synch with the rest of the film. That line wasn't in the screenplay, but Grant insisted that he have some "Cary Grant lines" and wrote that one himself. Thirty years later, Stone still laments it. Nevertheless, there are many other examples of Grant being goofy in ways that cut against his character's status as potential villain.

- If you know me, you know that this part of the film was more or less wasted on me, but fashonistas should see this movie on the basis of Audrey Hepburn's clothes alone. The joke is that the movie opens with her husband leaving her destitute; all she has is in a few suitcases. But from those suitcases comes Givenchy, Givenchy, and Givenchy, one outfit after another. With the caveat that I know next to nothing about clothes, this was my favorite:

- That's apparently what the well-dressed woman wore to lay on a pauper's cot and think pensively about their dire situation, circa 1963. Classic!

- This isn't a film with a lot of flashy camerawork. I did like the corpse-eye view of the morgue drawer closing on Hepburn's late husband, however:

- It's a little self-conscious, particularly in a film that doesn't have Hitchcock-style camera movement anywhere else. But that mortician's face is so perfect from that angle (and there's a nice match cut to a hand closing a desk drawer in the next scene) that I find it hard to hold it against anyone.

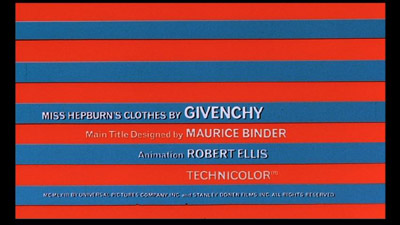

- Henry Mancini's score for this is exceptionally cool, at least when it's in the opening-credits arrangement, with wood blocks and surf guitars, and not the Johnny Mercer ballad version. Those opening credits are also noteworthy for their epileptic-unfriendly animations and garish colors:

- Yes, those animated flowers are rotating about once every three frames. The titles were done by Maurice Binder, who also designed all the Bond title sequences through License to Kill. Charade doesn't have any naked women as major features of the titles, however. Oh, and if you're wondering why there's a Johnny Mercer version of the title theme in the movie, it's so it could qualify for an Academy Award for "Best Song"—you have to have lyrics to be eligible. Charade was nominated, but lost (to the well-remembered and universally loved "Call Me Irresponsible," from Papa's Delicate Condition).

- Peter Stone wrote Charade as a screenplay at first, and when it was rejected by every studio, he rewrote it as a novel (and not a very good one, by his own admission). However, it was good enough to serialize in Redbook, which got him enough attention to sell the movie rights, then resell the original script as his "adaptation" of his own novel. Another illustration of the mental real estate principle there: an original screenplay is nothing, but if it's an adaptation, well, that's something else.

- And speaking of gaming the studios, Donen and Stone only touch on this briefly, but it seems that the film was set up at Fox, went into turnaround when Grant dropped out, was picked up by Universal, and then Grant came back, much to Universal's dismay. I'm not sure, but I think Donen (who produced) may have made a great deal of money by switching studios. Unfortunately, Variety's online archives don't go back far enough to see what the deal was.

- According to the IMDB, Charade is in the public domain because of a copyright screwup at Universal. This seems borne out by the number of different editions available on Amazon, but the Criterion DVD lists it as "Under exclusive license from Universal Studios Home Video, Inc. © 1963 Universal Pictures Company, Inc. & Stanley Donen Films, Inc., All rights reserved." A little research reveals that the controversy comes down to this frame:

(Click the image for an easier to read full-resolution version).

- The copyright notice in Binder's title sequence does not include the copyright symbol, "©," which was apparently required by law until 1989 for a work to be copywritten. So for a long time, anyone who wanted to release a video or DVD of Charade just had to get their hands on a print and do a transfer. This doesn't mean it was ok to copy the official Universal DVD (under separate copyright as a derivative work), and I bet the studio wouldn't have been too happy if I'd walked up wanting to "borrow" the negatives for a few days. However, recently studios have been doing all they can to remove movies from the public domain through back-door legal arguments. In the case of Charade, Universal still owns the copyright on Mancini's score, and they've taken to enforcing this claim. So it seems that for all intents an purposes, is not in the public domain any longer. Too bad, because I had a nice four disc set planned for a fall 2007 release...

- I kind of enjoyed that misleading Matthau/Hepburn still at the beginning of this essay. So here's one more, a bit of a spoiler. This is the shot in which the mastermind behind the criminal plot is revealed, as he coldheartedly orders his henchmen to murder Hepburn:

Wait for it...

Wait for it...

- One of these days I'm going to write an essay about one of these movies no one is likely to watch, and every last "fact" will be completely made up.