Insomnia, 1997, directed by Erik Skjoldbjærg, written by Nikolaj Frobenius and Erik Skjoldbjærg.

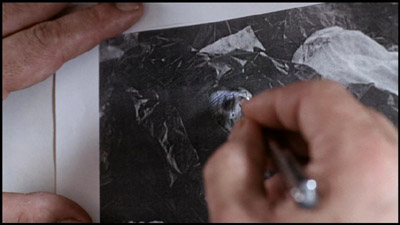

Insomnia begins with a scene that opens a thousand police procedurals: a man on a plane looks at a grainy photostat of a corpse. We all know how to read it, too: she's just been murdered, he's been called in to solve the crime. It's comfortable and familiar. Until the detective takes out a ballpoint pen and starts idly scratching out the victim's face.

The first act ofInsomnia is filled with moments like that; scenes that begin like a run-of-the-mill police procedural, but go slightly, uneasily off-kilter. I've seen it four times now, and it still makes me queasy. A lot of this has to do with Stellan Skarsgård's excellent performance as Jonas Engström, a man whose guilt is making him lose his grip on reality. Scratching out the victim's face on the plane flight up is only the first scene that makes clear that Engström is not the sanest guy you'll ever meet. He smells the vicitim's hair during an autopsy, then caresses her face until he notices a female detective staring at him:

Engström, it turns out, is in Norway because he can no longer work in Sweden after being discovered "in intimate conversation" with a witness. And if you know the undying and irrational emnity Swedes and Norwegians have for each other, you know that he's fallen far. To make things worse, he's been assigned a case in the far north of the country, where the sun doesn't set during the summer. In the plus side, he's working with longtime partner Erik Vik, played by Sverre Anker Ousdal. Vik is Engström's link to human warmth, and they relate to each other like an old married couple: Engström pulls things out of Vik's jacket pocket without asking, Vik falls asleep on planes with his head on Engström's shoulder. So when Engström mistakenly kills Vik while trying to apprehend a suspect, he goes a little crazy. And by "a little crazy," I mean "batshit insane." Here he is at his worst:

He doesn't look too together there, obviously. He's hiding behind that door because two local teenagers came into the room while he was planting evidence to frame one of them for murder. And he hasn't slipped out of the room because he's watching them have sex. We already know he likes one of the two teenagers, Frøya (played by Marianne O. Ulrichsen, who was also the production's assistant director):

And we know he likes her, because, despite her tender age, he's slid his hand up her skirt while questioning her. So: how do you make someone this unlikeable the hero of your movie? You make the villain even less likeable. The killer that Engström is after is a writer named Jon Holt, and he's seen Engström shoot his partner. So Holt and Engström become secret sharers, and the revolting pleasure Holt takes in finding someone else who has killed (and in being able to maniuplate him) puts the audience squarely in Engström's column. You can get a sense of Bjørn Floberg's performance as Holt from the scene where Engström first meets him (on a cable car, in a scene that owes a little to The Third Man):

Holt's infuriating smugness is critical to the way Insomnia works. There's no limit to Engström's cold detachment (this is a man who thinks baby kittens are "disgusting"), but he's downright charming next to Holt.

The second key to this movie is that Skarsgård's performance and Skjoldbjærg's direction make it clear that Engström is paying a great psychological toll for the things he has done. It's not called Insomnia for nothing, and even before Erik's death, we know that Engström isn't sleeping well. But as the movie progresses, Skjoldbjærg portrays Engström's insomnia in increasingly subjective ways. The slow fades-to-white that Skjoldbjærg uses in the second half of the movie do a very good job of conveying the horror of being unable to sleep in a place where it's dazzlingly bright all the time.

As you've probably noticed by now, Skjoldbjærg's palette is heavy on the whites and sickly greens (for what it's worth, so is Scandinavia). Insomnia is never pretty to look at; this is deliberate. You're meant to feel as isolated from and alienated by the surroundings as Engström.

As the atmosphere of guilt builds, the structure of the traditional police procedural is left far behind: Insomnia is a psychological study, not a thriller. Nowhere is this more clear than in the debriefing scene towards the end of the movie. After we've seen Engström cover up a shooting, frame an innocent kid for murder, molest a teenager, shoot a dog, nearly rape a hotel clerk, and look away while a paralyzed man drowns, we hear a clueless police officer tell him, "I have to admit you really lived up to your reputation. Never gives up...not until the case is solved." It's the last shambling attempt the movie makes to look like a regular police procedural, and Engström's reaction (he walks out) mirrors the viewer's. Which is not to say we're totally identifying with him. The excrutiating last shot is a head-on long take of Engström driving out of town. He goes through a tunnel, and for once the movie takes us out of the dazzling brightness and into more traditional noir lighting. Skarsgård doesn't look at the camera as he drives; he's got a permanent thousand-yard stare. It's a measure of how well we know Engström by this point that it's a relief he doesn't meet our eyes.

Randoms:

- All the acting is exceptional, but I would be remiss not to mention Gisken Armand's performance. She's the movie's moral center (which is kind of like calling Eva Braun Hitler's conscience; she doesn't play a big role). But her performance is excellent; look at how much about her you learn from the way she holds up one of the victim's dresses:

- Technical, wonky information: Insomnia is the first film in the series to be encoded in anamorphic widescreen. Here's what that means, in a very simplified form: DVD players send out a video signal that's at 640 x 480; that's as much information as they can contain per frame. For a letterboxed, non anamorphic movie, a still looks like this:

- If you have a standard television, that's what you're used to seeing. An anamorphic DVD distorts the image to fill the entire screen, so if you were able to look at the frame data in an unadulterated form, the same still would look like this:

- By distorting the image, the DVD is able to use the full frame for image data, and store more horizontal lines of data. Depending on your setup, the anamorphic image is then either horizontally stretched to fit a 16:9 television, or vertically compressed back into a letterboxed image. The result is a noticeably better picture on 16:9 televisions and computer monitors with no loss of picture quality on standard televisions. Both of the images above have been shrunk to fit this page, but here's a full-resolution version of a letterboxed image, and here's a full-resolution version of an anamorphic image. From this point on, most of the widescreen movies in the collection are anamorphic; the exceptions are mostly movies where the transfer was done for an earlier laserdisc version, since laserdiscs are letterboxed. Of course, movies that have an aspect ration of 1.33:1 or lower can't be anamorphically encoded. Oh, and although the film itself is encoded anamorphically, the menus and extras are all encoded in 4:3. Which means if you don't have a high-end DVD player that correctly reads the aspect ratio flags (I don't), you have to switch between aspect ratios when you move from the movie to the extras. Poor form, Criterion!

- If you want to know whether you can make two movies with the same plot points and roughly the same tone but have them be about completely different things, I direct you to Christopher Nolan's 2002 remake of this film. There are things an American star can't do, and so Al Pacino's version of the Stellan Skarsgård character is, well... different. Here are a few points of comparison:

- Pacino is in Alaska because the bastards at internal affairs want to put child molesters back on the streets and he needs to be out of town while things cool down. Skarsgård is in Norway because he fucked a witness.

- Skarsgård plants a gun at the house of the victim's boyfriend; Pacino is only there to prevent the Jon Holt character from planting the same gun, and unfortunately he can't find the gun in time to stop the cops from assuming he's the murderer.

- Pacino shoots the corpse of a dog that he finds in an alley when he needs to fake some forensics: Skarsgård kills a live dog.

- The American version of the killer is clearly dead when he hits the water at the end of the movie; the Norwegian one is clearly alive (and Skarsgård stands there while he drowns).

- Skarsgård skulks out of town after sucessfully covering up his own culpability in his partner's death; Pacino dies a hero's death after telling Hilary Swank's young cop not to cover up for him.

6 comments:

i knew there was something to me liking both the 1997 original and the 2002 remake for differing reasons too =].

thank you for hitting the nail in the head.

Yeah, man, I don't mean to shit on Nolan's version; it's all right (Robin Williams is great) -- but I saw it right after the Skjoldbjærg's version (mostly because the whole time I was watching Skjoldbjærg's I kept saying, "No *way* Pacino did that," and I wanted to see how they made that movie into something he'd do). Anyway, I'm glad you liked the post.

There can be no comparison in quality or sensibility between the two versions of the film - Nolan's remake is a Hollywood hollow out of a superbly complex, unvarnished original.

All Nolan's characters, and their relationships, are based on strict Hollywood stereotype, starting with Pacino's 'supercop' routine in the first team breifing;in the buddy act with his partner; and especially in the doe-like worship of the female cop (and the horribly cliched development of this relationship).

The plot is needlessly expanded with the background story of a previous frame up, and this plotline is used to ridiculous effect when Robin Williams tries to blackmail Pacino on the basis of his knowledge of Pacino's misdoings - how could he possibly know about Pacino's past in this way?. This device turns Williams into a 'Basic Instinct' style omniscient supervillain. In the original, the villain's character is, in contrast, both complex and utterly plausible.

Nolan's films is superbly made, but a standard issue money making machine. The ending is a gross cop out.

There are two depressing things about this:

* many critics do not seem able to sense the difference between real and fake.

* Nolan's Memento was much closer in sensibility to the original Insomnia than his remake. I really think he must have been got at by the Hollywood machine

Dan Usiskin

Great comments. I wrote a bit about the two films a few years ago on criterionforum.org and I'll add my points here too.

I agree with Dan, I had some hopes for Nolan tackling Insomnia head-on after his excellent films Following and Memento. I was sadly disappointed (and I think it was telling that the DVD was most interesting for the way one commentary broke the film up by shooting order, not for the film itself!) It was that bad it has kept me away from Batman Returns and The Prestige for now, although I have got the DVDs for when I'm ready to watch a Nolan film again (similar to the way Mission to Mars scared me away from De Palma for his next two films!)

I just couldn't believe that the remake was literalising all the themes treated so delicately in the original. The partner threatening Pacino was ham-fistedly done, compared to overhearing people talking about his indiscretion with a witness, that may or may not have happened in the original. And in a sense it didn't need to have happened - we live in societies where just a rumour of indiscretion or improper conduct can get people disciplined or fired. That sequence in the original is incredibly important in bringing the viewer in to Engstrom's paranoia and to suggest a reason for his mental state.

I think this also reflects in the scenes with the hotel clerk and the girl in the car. Is he wanting them to report his conduct to the police because he can't do it himself?

And the dog - changing that really upset me. It was just too convenient for there to be a dead dog lying around in exactly the place Pacino's character goes to be sick, let alone for it still to be around when he returns later on. Plus killing the dog raises a lot of moral questions that an audience doesn't have to be confronted by with the corpse. Every situation is twisted around to make the character more sympathetic in the remake, while in the original, as you pointed out in your review the audience is constantly confronted with the character's actions.

It is very interesting that two Crierion films have probably the best use of the stare to brilliantly close out a film, albeit for different purposes: Insomnia and The Long Good Friday!

Don & Colinr,

Yeah--what you said. Don't be too harsh on Nolan though; you can't make a movie like Insomnia with a star. Anybody who comes from the independent world is bound to have problems the first time they fully enter the Hollywood system. Although The Prestige is no Memento, I think Nolan is figuring out how to make interesting movies from inside that system.

Our normal associations with daylight are completely upended in Insomnia. The perpetual daylight is sinister and obfuscating, even blinding…all the things we usually associate with the dark. In fact, for all we can see beyond most of the windows throughout the film, it may as well be a pitch-black, moonless night out there. This is particularly discomfiting because it subverts daylight’s normally positive connotations. It is off-kilter and upsetting for us in the same way that an erudite, well-mannered cannibal is scarier than Jame Gumb.

Daylight is a palpable presence in this film, and it is not a good guy. Anything could be lurking in that light. And if we’re not safe in broad daylight, we’re probably never very safe at all. The blind in Engstrom’s hotel room lifts up a few inches seemingly by itself, but our sense is that something supernatural is controlling it. Or in a later scene a beam of harsh daylight blazing through a hole in the same blind almost feels like an eye watching Engstrom toss and turn in his bed. It’s interesting to realize that all the deaths (Tanja’s, Vik’s, Jon Holt’s) are accidental. It’s as though something unseen had some hand in them.

Perhaps I’m overreaching. After all, if anyone were to label Insomnia, they’d call it a thriller or police procedural. No one would call this a ghost story. I wouldn’t either. But I do think there are suggestions of something unnamed concealed in that light.

Post a Comment