Nights of Cabiria, 1957, directed by Federico Fellini, screenplay by Ennio Flaiano and Tullio Pinelli, with additional dialogue by Pier Paolo Pasolini.

If I made a list titled "Good Settings For Physical Comedy," I think "An Aging, Low-End Prostitute's Descent Into Penury" would be toward the bottom. Which means I would never have made Nights of Cabiria, a film that owes as much to City Lights as it does to The Bicycle Thief. Mixtures of pathos and comedy fit somewhere on a continuum from Waiting for Godot to The 40-Year-Old Virgin. As you would expect from its subject matter, Nights of Cabiria is more Beckett than Apatow, but Fellini isn't afraid to have his star walk into a glass door when the mood needs lightening.

Nights of Cabiria shifts so effortlessly between the heartbreaking and the comic that it's easy to forget how badly the movie could have gone. It's about that most sentimental of stock characters: the hooker with the heart of gold. It's easy to imagine a lighthearted version in which Cabiria is lifted from her sordid surroundings (and that version is called Pretty Woman). Or the movie could have gone the other way and been a turgid "gritty" drama about life on the Roman streets. In its bare outlines, the story is an encyclopedia of cruelty: bad people do bad things to our good heroine. But Cabiria is so fully realized and human that she defies stereotypes. Credit for this goes entirely to Gulietta Masina, who captures Cabiria's loneliness and pride in every frame. She's got a face for the ages:

Most of the movies in the collection so far have showcased the work of directors or writers, but Nights of Cabiria is an actor's movie. Masina has a preternatural talent for both broad gestures and more nuanced ones. The most celebrated example is the sequence where she is picked up by a film star named Alberto Lazzari and taken dancing at a nightclub. She's the shortest person in the room, out of her league culturally and financially and pretty clearly intimidated. But once Lazzari takes her on the dance floor, she does this crazy outsized mambo and owns the room (not necessarily for the right reasons):

If this were Pretty Woman, the scene would be all about Cabiria's infectious enthusiasm winning over a crowd of stuffed shirts. It's not, though; as the movie makes clear again and again, none of Cabiria's adventures end happily. This one ends with her sleeping on the bathroom floor while Lazzari enthusiastically reunites with his girlfriend.

Smaller details are just as keenly observed. My favorite is at the very beginning: Cabiria has just narrowly survived being thrown into the Tiber by a lover who wants to steal her purse. Understandably, she's a little upset.

You can't show it in a still, but when you see the film, pay attention to the way she taps her cigarette, starts to light it, then loses her train of thought and forgets about the cigarette. On paper, it sounds like a showy bit of actor's business, but it's not; I didn't notice that she'd forgotten to light it until the second time I saw the scene.

Nights of Cabiria lives or dies on Giulietta Masina's performance. I think it would be hard to make a bad film with her playing Cabiria. That said, Fellini's direction and Piero Gherardi's production design don't hurt. You could say of Cabiria, as Martin Amis said of Austen, "Money is a vital substance in her world; the moment you enter it you feel the frank horror of moneylessness." I was impressed with the ways Fellini and Gherardi imbue that class awareness into the locations and props. The most ostentatiously wealthy person she knows is a pimp with bad sunglasses and a Fiat 600:

Attention to little details like the car makes all the difference in making you aware of how much money matters in this world. The locations are also carefully chosen. Cabiria doesn't work the Via Veneto, but the Terme di Caracalla, a hangout for prostitutes to this day. Best of all is Cabiria's house, a cinderblock cube in the middle of a wasteland between Rome and Ostia. In 1956, Rome was undergoing its postwar expansion, and Cabiria's neighborhood is on the edge of that sprawl. You can see the city transforming itself into something bigger and uglier in the background of almost every shot, even the first:

I'd be willing to bet that there's a terrible block of terrible apartments now where they're standing.

There's nothing about any individual production design choice that's really showstopping. Instead, Gherardi and Fellini make Cabiria's world credible through a slow accumulation of small details. This is what sells Masina's performance when it switches from charming to heartbreaking, when you realize how badly she wants to change. Most people seem to think this happens when Cabiria and her friends make a disastrous pilgrimage to the Sanctuary of Divine Love. But to me, the moment the tone really shifts is a summer afternoon she spends out in the country sometime later.

Masini's performance borders on melodramatic here, but I think the scene captures the way idleness can be unspeakably depressing when you're afraid your life is going the wrong direction. But then I'm the kind of person who takes it for granted that religion won't offer much solace, so the pilgrimage sequence offered no suprises for me. In the later scene, getting drunk fails to cheer Cabiria up. Now that's horrifying.

To the extent the movie has a formal structure, it's a retelling of the same story in successively louder tones: Cabiria finds something she believes will make her happy, but it ends in disaster and humiliation. So the last act is hard to watch: she meets a man who wants to marry her, open a shop in the country, and grow old together. Cabiria doesn't know what kind of movie she's in, but the audience does, and it's not a romantic comedy. The beautiful locations toward the end are to the Roman scenes as Lazarri's villa is to Cabiria's house, and if you've been paying attention, you know that Cabiria won't be allowed to enjoy them for long. It's a rare movie that can fill a shot like the one below with menace.

It's worth noting what makes the last sequence as nerve wracking as it is. Fellini sets up a number of points where you expect Cabiria's new lover to betray her. But instead of the humiliating disaster you've been conditioned to expect, Fellini uses each scene to give you more information about how much Cabiria has bet on this last chance at happiness, financially and emotionally. It's excruciating, but it serves a purpose: the higher Fellini ratchets the tension, the more strange and wonderful ending is.

More than almost any other film character I can think of, Masina's Cabiria seems fully realized to me. It's not that she's particularly realistic in the sense that anyone I've ever met is like her. But I think it's precisely that uniqueness that makes her so alive; she's a true original, as vibrant and sad and suprising as anyone you will ever know.

Randoms:

- Alberto Lazzari, Movie Star, is played by Amedo Nazzari, Movie Star. It probably wasn't too much of a stretch for him.

- Of all the great Roman locations, the shot that really got me was this one:

- That's Termini, looking just as I remember it from 1995. Apparently it's different now; the station was renovated in 1998 and nothing in current photos is recognizable to me.

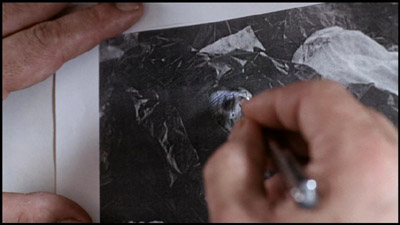

- And speaking of renovations in 1998, Nights of Cabiria was cleaned up for a theatrical rerelease that summer (while we were all watching Armageddon). It may be the best example of film restoration ever. Here's what it looked like on video in the states until that summer:

- And here's roughly the same frame from the Criterion edition (made from the 1998 restoration):

- Look at the detail on the dog's face and Masina's hair—it's like a different movie.

- The subtitles were also rewritten for this release. Unfortunately, the scene they chose to show in the DVD extras as an example of this rewriting has the one line that jumped out at me as a bad translation when I saw the movie. Cabiria is burning everything an ex-boyfriend left at her house (it's the ex who "broke up" with her by "stealing her purse and pushing her into a river to drown"). So she's in a hell of a mood and is yelling as she throws his stuff in the fire. The original subtitle for one of her lines read "Who'll feed him now, my fine good-for-nothing?" Which doesn't make much sense. The new one reads "And who's gonna feed you now? St. Peter?" That's an improvement. But the line (in a bad phonetic transcription of dialect) is actually "Do vai a mangia? A San Pietro?" In modern Italian, that would be "Dove vai a mangiare? A San Pietro?" Which is literally "Where are you going to eat? To Saint Peter's?" It's a name, but it's also a place.

- This version of the film restores a sequence that was cut out before the film's release, reportedly at the request of the Catholic Church. At least, that's the story everywhere I can find it, except in an interview with Dino Di Laurentiis on the DVD. He claims that he and Fellini fought long and hard over that sequence because he believed it brought the action of the movie to a screeching halt; his version of the story ends with him stealing the negative so Fellini couldn't use it. Reports also vary as to whether that scene was ever shown; Fellini writes that it was shown at Cannes, but this doesn't square with De Laurentiis's version of the story or the more common story of church interference. In any event, the sequence was restored from a print found in France, so it may have screened at least once.

- The company logo on this is Paramount's, and the title reads "La Paramount Presenta." Did Paramount have a European distribution branch in the fifties?

- The screenwriters relied on Pier Paolo Pasolini for help with Roman slang. Yes, it's the same Pier Paolo Pasolini who directed Salò. No, nobody eats shit in Nights of Cabiria. Stop worrying.