Taste of Cherry, 1997, written and directed by Abbas Kiarostami.

Everyone who has written about Taste of Cherry has to find some way to deal with the fact that this is an incredibly slow movie. Some people describe it as "languid," or "deliberately paced." Everyone uses the word "meditation" at some point. One synopsis reads, "When Kiarostami directs, the doors are opened to metaphysical reflection." That's undeniable. But the doors are opened to metaphysical reflection when staring at a blank wall, too.

People seem to enjoy this movie to the extent that they fill in the long, slow shots with thoughts of their own. I suppose that this is a fitting response to Taste of Cherry, a languidly paced meditation on the unbridgeable distances between people. I think Kiarostami takes boredom as a narrative strategy about as far as it can be taken, however, and although I liked the movie, it's an exhausting experience and not one I would recommend to most people.

The phrase "boredom as a narrative strategy" isn't entirely a joke. Here's Kiarostami describing what he likes and doesn't like in movies:

I don't like to engage in telling stories. I don't like to arouse the viewer emotionally or give him advice. I don't like to belittle him or burden him with a sense of guilt. Those are the things I don't like in the movies. I think a good film is one that has a lasting power and you start to reconstruct it right after you leave the theater. There are a lot of films that seem to be boring, but they are decent films. On the other hand, there are films that nail you to the seat and overwhelm you to the point that you forget everything, but you feel cheated later. These are the films that take you hostage. I absolutely don't like the films in which the filmmakers take their viewers hostage and provoke them. I prefer the films that put their audience to sleep in the theater. I think those films are kind enough to allow you a nice nap and not leave you disturbed when you leave the theater. Some films have made me doze off in the theater, but the same films have made me stay up at night, wake up thinking about them in the morning, and keep on thinking about them for weeks. Those are the kind of films I like.

I agree with Kiarostami that there are films that "nail you to the seat and overwhelm you to the point that you forget everything, but you feel cheated later." I think a lot of stylish, visually interesting, narratively dead films are that way (Oldboy, to name a recent example). But I also think that the best films, my favorite films, are the ones that nail you to the seat and overwhelm you, but for a purpose. And even a slowly-paced film (Andrei Rublev) can do that. But Taste of Cherry is more of a Rorschach blot than a movie; what you get from it depends on what you bring to it, more than any other film I've seen.

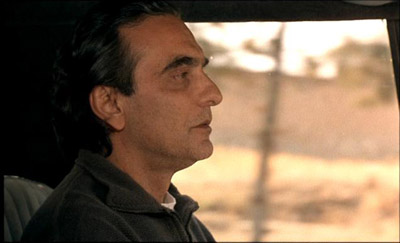

The film does have a story: Mr. Badii, a middle-class Iranian played by Homayon Ershadi, is driving around the hills to the north of Tehran trying to find someone to help him commit suicide. Most of the movie takes place in Mr. Badii's Range Rover:

And we see Badhii's passengers the same way. Here's Ali Moradi playing a soldier Badii meets:

The vast majority of the movie is one of the two shots above, or a wide shot of the Range Rover winding through the hills, as Badii and his passengers converse about suicide. Kiarostami does have an eye for interestingly framed shots, like this one, of workers converging on Badii's car to push it out of a ditch:

The flattened compostion here is striking, all the more so because it's one of the few moments that something is happening besides Badii's drive through the hills. And if Kiarostami doesn't care much about plot, he has even less interest in character. You know very little about Badii, less still about the other characters. Part of the point is that you can't know the things that really matter about any of these people; this is central to Badii's view, at least. Here's his answer when asked why he wants to die:

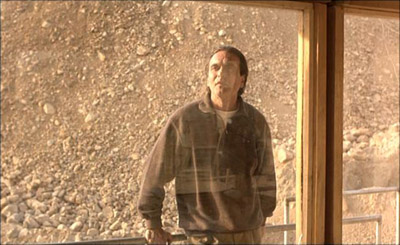

It wouldn't help you to know and I can't talk about it. And you wouldn't understand. It's not because you don't understand but you can't feel what I feel. You can sympathize, understand, show compassion. But feel my pain? No.A lot comes down to whether you agree with him or not. The movie, at least, goes out of its way to make viewers aware of the unbridgeable gulf between this character and our own lives, and not just by severely limiting what he tells us about himself. When Badii's not in his car, there's usually something between us and him, most often glass.

The second still shows Badii either taking his sleeping pills or not, before taking a taxi to the grave he's dug for himself. In a standard film, this would be the moment of revelation; in this one, we see it in a long take from outside his apartment, behind curtains, and never know what he's chosen. The one moment Badii seems to break through his carefully controlled facade, our view of him is obscured by rock dust from some sort of quarry.

Kiarostami keeps this strict distance between viewer and characters, as though he's treating their inner lives with respect or allowing them to keep their dignity from us. But of course, these aren't real people. For me, the most beautiful shot in the movie was of Badii's shadow, cast on a pile of dirt falling through a sifter at the quarry. As long as the dirt continues to fall, there's a surface for him to cast a shadow on; at the end of the shot, the dirt ceases, only the grid remains, and Badii's shadow diffuses onto the equipment below him.

It's a really beautiful reminder that what we're watching is transient and fictional. I'm not sure that Kiarostami wants us to make the next connection, to say that human life is as transient as Badii's shadow, mostly because of the ending of the film. Here's how it ends: we see Badii lie down in his grave, and cut from a point-of-view shot of the sky over Tehran to a close-up of Badii's face, intermittently illuminated by flashes of lightening, as he closes his eyes. It's not clear whether he's dying or going to sleep, and the screen goes black. But lest we ponder the question too long, Kiarostami jarringly cuts to grainy video footage from the making of the movie; we see Homayon Ershadi smoking a cigarette on location as Kiarostami and his crew work on the movie. Whatever imaginative connection viewers have drawn between themselves and Mr. Badii are purely illusory; he doesn't exist. As the instrumental parts of Louis Armstrong's version of "St. James Infirmary" plays over the credits (the only non-diagetic music in the film), we are forcibly reminded that when thought we were watching Badii, we were, in fact, alone with our own thoughts.

Randoms:

- The sound mix (by Mohammad Reza Delpak), is much more subtle and interesting than the cinematography. Sound is treated more realistically in this film than in most I've seen, from muffled and misheard parts of conversations to the distant sound of a helicopter or children. It's also the first movie I've seen where the mixer got a before-the-title credit.

- Roger Ebert hates this movie. From his review: "A case can be made for the movie, but it would involve transforming the experience of viewing the film (which is excruciatingly boring) into something more interesting, a fable about life and death." I didn't hate it, but I'm not planning on watching it again.

- I think that some of the moments that moved me in this film benefited from how boring the scenes around them were. (By the same token, I think Fishing With John is all the funnier for how spread out the funny parts are). I don't think this is a strategy I'm going to be able to use myself, so if it seems like you can do something with it, go nuts.

8 comments:

I am a huge fan of this film, and at timed I think people are trying to niche a film into something when it isn't anything. The movie barley has any plot, the cinematography is boring, the dialouge is rigid, adn the only lines that really catch any attention were those about the taste of cherry. To me this film is just a master piece of existentialism. The way the film concludes, reminding you that nothing you just saw matters, Mr. Badii doesn't matter, his life doesn't matter, and neither does this movie your watching, and that's why I refuse to end it. Thinking about the movie from that perspective, that the movie is simply doesn't matter, much like our lives I think the movie can pick up a life of its own. That's what Kiarostami does in many of his films, he cares about the final feeling, and tone he sets, rather then the expierence of the film. For example he has this documentary about a massive traffic jam, that he films entirley in tight close ups. In the end you feel unbelivably clostraphobic, like those that were stuck in the traffic jam, even though the movie was a complete bore to watch. So I geuss with Kiarostami the real question you need to ask is "At the end, how did I feel?"

I have just seen your blog and you reaaly are doing a great job. I think some more recent spines, especially after 200, are more interesting but there clearly are many important films that you have already reviewed.

Taste of Cherry is one of my favorite Criterions and I don't agree with you on most points, but you did get why I ( and a lot of other people ) love this film. This film reminded me so many little precious details that make life much more interesting. And it had the irony that all these things are so little that the only thing we evetually see is a huge meaninglessness.

And when a film is trying to tell us how insignificant and little our lives and problems are, it's only even more meainigful that not much happens in it. I think the life in a mountain in Iran is not much more different than what we see in the film, so for many people, there is nothing woth filming here. But the life is worth filming, not because anything interesting happens, but because it exists.

The cinematography of this film is gorgeous in comparison to Kiarostami's many other films, especially 10.

Anyway, I'm happy to discover your blog and you really have some writing talent.

Jack,

I can see what you're saying here, and I understand what Kiarostami is achieving. Perhaps it's my attention deficit disorder, however, but I see boredom as an evil in and of itself. There's a difference between thinking something out, or meditating, and being bored. Don't you think it's a lot to ask for two hours of the audience's time if you're going to make those two hours excruciating? It's just not my cup of tea; I think the movie is much more interesting to think about than it was to watch. I guess that's better than being more interesting to watch than to think about, though...

Eren,

Thank you—I'm glad you're enjoying the blog. I agree that Kiarostami does a good job of showing that most things don't amount to much, so to speak. But I'm not sure that he really cares that much about the little details. I wonder if you've read Transparent Things, by Vladimir Nabokov? Your description of Kiarostami's project reminded me a little of the story of the pencil in the third chapter (it's online here -- although Nabokov is making precisely the opposite point, that even the most insignificant detail has a strange and interesting history attached if you look closely enough. For me, that's more the way the world works; things may be ultimately meaningless, but that doesn't mean the stories we attach to them aren't interesting.

So glad I found your blog. I was searching for an explanation of the end of this film, Taste of Cherry, and you gave me a nice one.

Actually, I had to watch this movie over two nights because it was just too stressful for me. I did not find it boring at all, but was on the edge of my seat and my stomach was tied up in knots. I have done a lot of hitchhiking and come upon curious drivers like him. He gave me the CREEPS. Not knowing what he was all about, he could have been on the prowl for sex with strangers, or trying to kill someone randomly. It was TOO creepy to watch all in one night.

One question, do Iranians talk to each other so easily, and at such length? Or is this a peculiarity of our hero?

Watching Criterion movies is like reading a book published by Penguin, you just know it's gotta be good.

Once again, I liked this much more on a second viewing, “like” being relative to my first impression. There have now been two Criterion selections where boredom has been used as a narrative strategy: Fishing With John and Taste of Cherry. Boredom is a hard sell in any context but probably works best in comedy. If you want to foster metaphysical contemplation, ambiguity is the more useful tool (i.e. 2001 or The Tree of Life). And if a black or absent image of extended duration (when the protagonist, Badii, closes his eyes after lying down in his grave) represents not just a transition but a pause for contemplation, I would say that the first thought that comes to mind for most, apropos in a film about suicide, is “Is this finally over?”

The video tag ending Taste of Cherry is meant to tell us that nothing preceding it is real (which I didn’t need to be told). It is also meant to distance us emotionally from what might be perceived as a sad ending (but I actually like being aroused emotionally by film). Frankly, if everything I’ve been watching for 100 minutes is a meaningless fiction, then 100 minutes have been irretrievably lost to (or stolen from) me, and what I feel at the film’s end is resentment more than anything else.

But I’ll play Kiarostami’s game because I wasn’t quite as bored and I didn’t dislike this quite as much as I’m leading you to believe. Kiarostami is looking for an intellectual approach from his audience, so here’s my take on the ending: the documentary video footage that ends Taste of Cherry can be read as an allegory of the afterlife. Certainly with this footage we have crossed to “the other side” of the image. And while some may find Badii’s descent into the grave as ambiguous, Kiarostami himself had this to say in “Taste of Kiarostami” by David Sterrit in Senses of Cinema:

“The scene at the end—where you see cherry blossoms and beautiful things after he’s died, has the message—that he has opened the door to heaven. It wasn’t a hellish thing he did, it was a heavenly transition.”

So this is an existential film to which Kiarostami has added a happy ending. Once the taxidermist agrees to help Badii, the industrial sounds of earthmovers and diggers so prevalent until this point (and ironic during Badii’s unsuccessful attempts to find someone to bury him) begin to recede, replaced by the chirping of birds--already the heavenly transition has begun. And there is peace as Badii watches his final sunset. In the video footage Badii, visually boxed in throughout the film narrative, wanders freely about a suddenly verdant landscape interacting with his creator Kiarostami, and his first impression in this afterlife is the sound and sight of a troop marching and counting cadence, recalling the best time of his life.

(I've skipped The Red Shoes since I have an opportunity to see it on a big screen in Tampa at the end of August.)

Matthew, and the commenters over time,

I saw the film for the first time last night as though through a reversed telescope - in the sense that I'd already seen Kiarostami's Certified Copy, almost 15 years into the future, so to speak. So I was primed to expect ambiguity, and an ironic reflexive commentary on the nature of film and narrative.

The "point" of A Taste of Cherry, isn't (only) existential, it struck me. Rather it's (also) a vehicle for interconnected cameos of life in Iran - the wasteland contains in addition to the bleak industrial sites several poeple's lives and a brief look at their lives and stories. This goes some way to explain why Mr Badii inquires about where they come from, what they do, and so on. The somewhat flowery modes of address are both a reflection of time-honoured politeness, and something more substantial: the phrases are relevant to deep questions about life ("Are you well?"). One of the themes is the genuine hospitality and concern most of the characters have towards the protagonist, whether or not he rejects their offers.

Overall, the "non-existentialist" dimension seems to concern narratives about, and ways of looking at, the world at its most concrete, dusty, and real. The ending simply adds the filmmaker's narrative and "ways of looking" to the whole, in a rather Brechtian way exposing the frame of the cinema lens.

It lends itself to the idea that even though deeper meanings and answers might remain tantalizingly out of reach, possibly permanently, the world is a presence that repays attention and careful observation - Nabokov's pencil, in other words, by a different artist.

The interaction between the subjective or personal 'frames' and the world as it appears through and in it, seems to me to be the real subject of the film. At least, it helps me make more sense of Kiarostami's predeliction for looking at his characters through windows, inside cars, with the landscape rolling by outside often reflected in the glass; and the way in which faces, figures and fragments of conversation keep floating into the car interior through the half-open side windows. In this light, even the slight winding down of the window that Mr Badii has to do in order to take a snap of a happy couple, carries a larger meaning beyond merely a random action.

Your loyal reader,

Neville

John & Neville,

Those are both fascinating readings of the film; the quote from Kiarostami re: the ending is great. (Although: Taste of Kiarostami? Really?) Neville, good call on the use of the windows -- I wonder if I would have noticed that if I saw the film again now.

Post a Comment