The Most Dangerous Game, 1932, directed by Irving Pichel and Ernest B. Schoedsack, screenplay by James Ashmore Creelman, from the short story by Richard Connell.

The Most Dangerous Game seems doomed to languish in the shadows of the other film Schoedsack and producer Merian C. Cooper were working on in 1932; an obscure art-house gem called King Kong. But although it's not a groundbreaking special effects masterpiece, The Most Dangerous Game stands up very well on its own. I actually enjoy watching it more than Kong, mostly because it is so quickly paced (it's all of 63 minutes long).

The movie, like the story, is about a famous big game hunter named Rainsford who finds himself washed ashore on an island in the Pacific. There he meets Zaroff, a Cossak aristocrat who has retired to the island in the wake of the Russian revolution. The two men share a passion for the hunt, and Zaroff is delighted to have Rainsford as a guest. Rainsford is more than happy to be there, until he realizes that Zaroff hunts a little differently than he's accustomed to.

I've written about the problems David Lean and his collaborators faced when adapting Dickens; you can't film half of a Dickens novel in a reasonable theatrical runtime. The creators of The Most Dangerous Game faced the opposite problem. The story, beloved of middle school English teachers, clocks in at just over 8.000 words. You could probably film a ten minute version that remained faithful to the original text. That wouldn't endear you to studio heads who'd asked for a feature, however. So to stretch Connell's story to feature length, Creelman had to pad it a bit. What did he add? Well, James Creelman also worked on the screenplay for King Kong. Here's that movie's fictonal impressario Carl Denham talking about his art:

I go out and sweat blood to make a swell picture, and then the exhibitors and critics all say, "if this picture had a love interest, it would gross twice as much." All right, the public wants a girl, and this time I'll give 'em what they want.

So here's what the public wants:

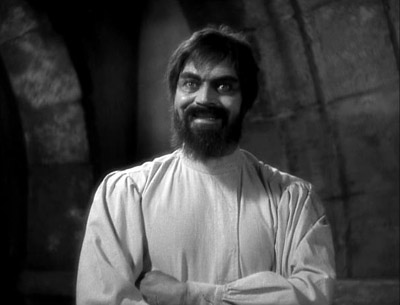

Fay Wray, playing the woman in distress. In the story, Rainsford is Zaroff's only guest; in the movie, Wray's Eve Trowbridge and her brother Martin (played with aplomb by Robert Armstrong, also in Kong) are recipients of Count Zaroff's unique form of hospitality. Zaroff, as portrayed by Leslie Banks, is one of my all-time favorite screen villains. Here's his entrance:

As you can see, he's that most dreaded of American villains: the European Aristocrat. He may look a bit ominous in this shot, but Rainsford meets him after trying and failing to have a conversation with Zaroff's mute servant, Ivan. And compared to Ivan, Zaroff looks warm and welcoming. It's Ivan who answers the door, and listens to Rainsford's pleas for help, with the following expression:

Zaroff, sensing that Ivan has been rude to his new guest, orders him to smile. He does:

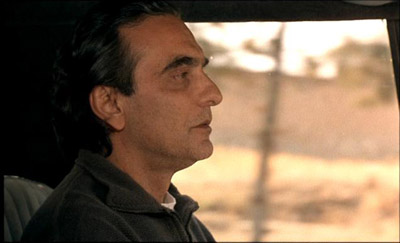

And things just get more unpleasant from there. As you can see, this isn't particularly subtle filmmaking, but it's a hell of a lot of fun. Leslie Banks performance is fantastic to watch, start to finish. He was injured in World War I and the left side of his face was paralyzed, which means that in scenes where he is meant to appear civilized and welcoming, he is nearly always shown in profile, as below:

That's the Count talking to Rainsford for the first time. And yes, that's Joel McCrea playing Rainsford. Anyway, in profile, Banks looks normal. But when he's meant to be creepy, he's shot straight on, letting you see his bulging eye and asymmetric features:

You can't do that kind of thing with makeup. The still above is from the end of one of my favorite exchanges: Fay Wray is going to bed, leaving her increasingly drunk and obnoxious brother with Count Zaroff. She urges her brother to get to bed early, and he replies, "Don't worry! The count'll take care of me, all right!" At this, Zaroff looks at her forbiddingly and says, "Indeed I shall..." and the camera does this fantastic dolly towards him staring up the stairs at Fay Wray. It need not be said that the brother is never seen again. If that kind of Grand Guignol dialogue sounds like fun to you, rent this movie immediately; it's one of the best of the sort I've seen.

One of the reasons it's so great is that Zaroff is, for all his campy dialogue, genuinely creepy and threatening. If you haven't read the story, and you haven't figured out what Zaroff is up to on his island, here's a shot of his top-secret trophy room:

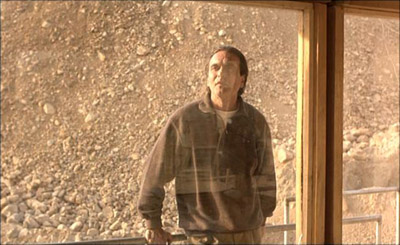

But while in the story he's simply a sociopath, in the movie his pathology is more complicated and more frightening. For one thing, the trophy room is a gruesome invention of the filmmakers, and I think it stands up to modern horror standards. For another thing, Zaroff explicitly links hunting with sexual desire; he only wants women immediately after the kill. It's apparent that he plans to rape Eve Trowbridge once he kills Rainsford. It's possible he's brain-damaged; he has a scar from an old head wound that he strokes absentmindedly when in the grip of his madness. And although he has actively sought isolation from the outside world, he desperately wants companionship and understanding. He believes that Rainsford is the one man on earth who can understand him (as Rainsford has written a series of books about hunting which are very Darwinian), and his fury when Rainsford is disgusted by his hobbies is horrible to behold. Of course, the lighting doesn't help:

Don't get me wrong; Zaroff is not a character we're meant to sympathize with or feel sorry for. But his psychology is more complicated than one would expect from the time period, and Banks makes him mesmerizing to watch. The fact that he depends on killing for sexual arousal makes him the precursor of a thousand slasher movie villains. He's not crude in the same sense that, say, Leatherface is, however; I'd put him head-to-head with Hannibal Lecter, that other villainous aristocrat, any day of the week. I think The Silence of the Lambs owes this movie a great debt, and not just for the scene where the heroine finds a pickled head in a jar:

Of course, Eve Trowbridge and Clarise Starling don't have that much in common; Wray is playing a passive character who seems most notable for her ability to open her eyes wider than should be humanly possible when she's horrified:

But while Eve Trowbridge isn't a particularly interesting character, adding her to the story is what makes Zaroff seem so much more awful than he does in Connell's version. This is the rarest of occasions: the addition of a superfluous character vastly improves on the source material. The Most Dangerous Game has other, more sophisticated virtues: the way Rainsford has to embrace Zaroff's philosophy to leave the island, and the fact that there's not too much difference between the way Zaroff "wins" Eve's affections and the way Rainsford does. But if you need more than Leslie Banks and severed heads mounted on walls, we're not coming at films from the same perspective.

Randoms:

- Ivan, Zaroff's taciturn servant, is played by Noble Johnson, who also appeared in King Kong. If you look closely at the photo above, you can see that he's not so much Cossack as he is black. As well as a long career as an actor, Johnson was one of the co-founders of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Hollywood's first black production company.

- The Most Dangerous Game has more in common with King Kong than a producer, director, writer, and several actors. Both movies used the same jungle sets (on what is now the Sony lot) for their respective islands. If you look closely, you will notice some similarities in the two stills below. The first is from The Most Dangerous Game, the second from King Kong.

- As you can see from Fay Wray's closeup at the top of the page, Henry Gerrard, the cinematographer, favored extremely soft focus for his female star. It's pretty jarring, given how sharp the rest of the film seems, but every time we cut to a closeup of Wray, someone's been slathering vaseline on the lens. Wray didn't need that treatment to look good, as you can see in King Kong.

- Zaroff's hunting dogs belonged to Harold Lloyd, who loaned them to the production. They were Great Danes, and didn't look threatening enough, so the filmmakers had their fur dyed. Lloyd was apparently none too pleased.

- The fight scenes in this movie seem surprisingly energetic and elaborately choreographed for the period. Below, Rainsford flips one of Zaroff's henchmen over his back while Zaroff himself rolls of the chair where he's just been thrown. There are not many films from the 1930s with fistfights that still seem interesting. This is one of them.

- Cooper hated movies that glorified drunkenness, which is why Eve's brother is so unbearable and comes to such an unpleasant end. Both Cooper and Schoedsack hated hunting for sport, which made this story a natural choice for them.

- If you look closely at Zaroff's entrance shot above, you can see a gruesome tapestry depicting a centaur carrying off a woman. It's one of those decorating motifs you won't see at Ikea, and it's repeated spectacularly in his front door knocker, which requires the user to grasp the woman in the centaur's arms to knock. It's a really excellent piece of set design, and an immediate warning that all will not be sexually kosher in Zaroff's castle:

- In the original cut of the movie, the scene in Zaroff's trophy room was a full ten minutes longer, and featured Leslie Banks showing off several fully-stuffed and posed men, describing in detail how they were killed. This proved to be too gross for preview audiences, many of whom walked out during that scene; as a result, the scene was cut back to the head on the wall and head in a jar pictured above. The disc doesn't include the cut footage, which is too bad. To paraphrase Kennedy, some people see human taxidermy and say "Why," but I see human taxidermy and say "Why not ten minutes longer?"

I am never going to be President.