Tokyo Drifter, 1966, directed by Seijun Suzuki, written by Yasunori Kawauchi.

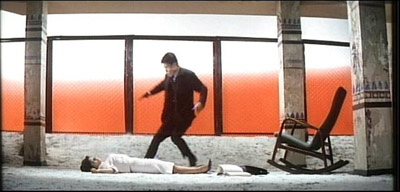

This is another one of Seijun Suzuki's movies for Nikkatsu, and, like Branded To Kill, it has a pretty banal script but is worth seeing for its lurid style. Suzuki got to shoot this one in color (he never made this decision himself, as he explains in an interview on the disc) and, well, never let it be said that he didn't use enough color. The exterior shots in this movie feature realistic looking streets, but the interiors are abstracted to the point of absurdity and feature eye-popping colors. This is easier to see than to describe:

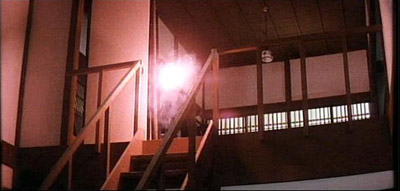

So, yeah, give Suzuki a color palette and he's going to make full use of it. Stranger still, the colors have thematic significance, which I'd seen in the theater but never on film (at least not so blatantly). Take the bottom still: the man in the red coat is Otsuka, the villain of the film. Pretty much any shot he's in, they'll be some other object arbitrarily colored red, which in this movie is also the color of violence. When the woman in the middle still is shot, the windows behind her are halfway colored red; later, Suzuki cuts back to that shot but the windows are now fully red, as though they've filled up with blood. His fidelity to this color scheme extends to the special effects: at a crucial moment, the hero's gun has a red muzzle flash, as below:

Thematic use of color isn't some great, startling invention, but I have never seen a movie that stayed so faithful to its initial rules. As with Branded To Kill, however, the question to ask is not whether Suzuki is stylistically inventive (he is), but what his style is in service of. And although Tokyo Drifter is a much more accessible movie than Branded To Kill and has a much more traditional style, it seems to me to have more going on beneath its surface than Branded To Kill did. It has a standard Yakuza plot, but scratch it and you'll find a critique of Japanese adoption of Western culture, customs, and economics after World War II. I don't mean to suggest that this movie is the work of a genius; in a lot of ways (the acting, for instance) it struck me as mediocre. But it's more interesting than it looks at first glance.

I'm not sure how much of the subtext of Tokyo Drifter is Suzuki's and how much was in Kawauchi's screenplay. I do know that Suzuki routinely made dramatic changes to the scripts he was assigned; in the interview on the disc, he says, "I believe if the script is perfect, there's no reason to make a movie of it." But some of the things in the dialogue are also played out in the set design, so Suzuki clearly had something to do with it. Here's the basic setup. Tetsuya Watari plays Tetsu, the right-hand man of a criminal boss named Kurata. Kurata is trying to go straight, and Tetsu is commited to helping him do it (the movie opens with Tetsu allowing a rival gang to beat him up rather than fight back and provoke them). Kurata is in the process of buying an office building from a man named Yoshii, and another criminal boss, Otsuka (the man in the red jacket above), wants to buy it from under him. The movie chronicles Tetsu's betrayal by his boss; he begins the movie fiercely loyal, and ends completely adrift.

Throughout Tokyo Drifter, Suzuki contrasts Tetsu's value system, based on loyalty, with Otsuka's, based on profit. This is the same thing you see in The Godfather, with the exception that Suzuki explicitly links Otsuka's values to western culture. You can pretty much tell how evil a particular character in this will be from how western they are. Yoshii, for example, is a capitalist; he owns the building that Kurata wants to buy, and he's making his living from interest. However, he's still basically a nice guy; he cuts Kurata a break early on, and he seems to represent the best that western civilization has to offer: an ethical business man. So you would expect that his surroundings would reflect that. And here's his office:

Yes, those are Greek frescoes on his walls: western, but not modern. Yoshii, by the way, gets killed about twenty minutes into the movie by Otsuka, who is more of a modern westerner. Otsuka's office is in the upstairs lounge of a club that's filled with teenage Japanese kids dancing to rock and roll, and one of his trusted hitmen drives what appears to be a 1957 Chevy. Tetsu's attitude towards this aesthetic, at least at the beginning, is exemplified by what he does to the Chevy: he steals it, drives it to a junkyard, and parks it here:

So that's a pretty simple dichotomy. What complicates it is that over the course of the movie, Tetsu changes from someone with a classic Japanese concept of loyalty into someone closer to the hero of an American Western. The movie ends, in fact, with an archetypical American Western scene: Tetsu rejects the love of a woman he used to pursue, and walks off into the night alone. If you have any doubt that Suzuki has American Westerns on the brain, halfway through the movie is a gigantic brawl at a "Saloon Western," complete with swinging doors, people getting hit over the head with chairs, and people being thrown out through a glass window right next to the bar. Western heroes don't form attachments to women; they act for themselves until they are forced to act. When the time comes, however, they use violence with great precision as a tool to defend the powerless. That's more or less where Tetsu is at the end of the movie, but he's definitely a Japanese version of this character; rather than killing his former boss, he gives him a broken glass and lets him commit suicide. I think the idea of honor is what replaces the idea of loyalty in a Western hero, and Tetsu's conception of this is a Japanese one. How long will that ideal stand against the western morality of money and power? Well, Tetsu does kill the bad guys and escape. But right before the last shot of him walking away, Suzuki sneaks in a montage of some neon signs around Tokyo that suggest that he's a bit more pessimistic than his script would suggest. The signs read, in English:

Copacabana.

NEW Latin Quarter!

SHOPPING ARCADE.

Randoms:

- I didn't have any random thoughts or facts about Branded To Kill, mostly because I had to work pretty hard just to make sense of it. Sorry.

- Tokyo Drifter marks the third Criterion Collection movie set in modern Japan, and the third Criterion Collection movie set in modern Japan that has a villiain wearing sunglasses. Do the Japanese hate sunglasses? Tokyo Drifter's version of this is especially jarring, as it features lots of closeups of Otsuka's glasses, like this one:

- In 1985, Seijun Suzuki was named the Best Dressed Man in Japan by the Japanese Fashion Society.

- The interview on the disc with Suzuki has what might be the secret to why the acting in this movie isn't so spectacular. Here's what he says:

Tetsuya Watari, who is the main character in Tokyo Drifter, is now one of the biggest stars in Japan. So, now I wouldn't want to say anything that would hurt his reputation, but I think... Tokyo Drifter was his first feature film, I am pretty sure of that. And I had orders from the company to make Watari a star. But, on the set, he couldn't say the lines when we called action. He froze and was speechless. In order to make him say the line, let's say he was sitting somewhere in the scene, the AD would hide behind the chair and hit him with a broom or something, then, I don't know why Watari could say his lines, but he did. That's the most memorable thing about Watari.

Not a big vote of confidence from your director, Watari.

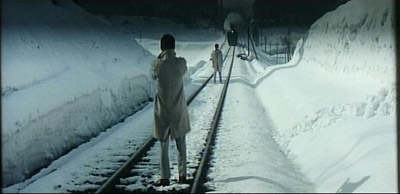

- After the great action sequences in Branded To Kill, I was expecting some excellent fight scenes. But the fights in this movie seemed too abstract to be much fun. The final gun battle takes place in a nearly empty room, bathed in light; it has nothing of the messiness that makes the action in Branded To Kill exciting. There is one very tense showdown in Tokyo Drifter, however (and, not surprisingly, it's set outside, where the surroundings are more realistic). I'll just put up a still and you can sort out what makes it tense for yourselves.

- In an interview I read about Kill Bill, Tarantino talked about how Japanese movies used blood in a theatrical way, and that that's what he was going for in the fight scenes of his movie. Seijun Suzuki is definitely from that school. The scene where Kurata cuts his wrists? Like an oil well in his sleeve.

8 comments:

I watched this movie last night and I thought it was another good film by Suzuki.

In your comments you talk about how the script was written and by whom. Do you have problems with the scripts of this andBranded to Kill? I'm wondering if you have problems with the translations at all. I found that the dialogue was quite juvenile. For example, the titles of both movies feel like bad translations. I think BTK should be named Marked for Death like the Segal movie. I'm not sure what the translation of Tokyo Drifter should be, but the concept of a "drifter" is hard for me to understand, as an American. The movie seems based on the Japanese interpretation of the cowboy stereotype. We were watching the Japanese ideal of this character, but when it was regurgitated back, it didn't make much sense. I thought some of that had to do with the translation of the scipt, but I could be wrong.

I really liked the style of this movie and was impressed with the use of color. I preferred BTK though because, like you said, it was not meant for international release. I prefer the glimpse into another culture that doesn't always make sense to me. Although, I did like the theme song to TD.

On a side note, the renting of the Criterion Collection of Japanese movies from the 60's has made me either obscure enough or respectable enough to have the owner of the video store where I rent remember my name. This is a first for me in LA and I am greatly pleased. Thank you thank you thank you!

J-

Yeah, it's always hard to judge dialogue and writing in a translated movie. I do think Branded To Kill could be a little bit clearer as far as what on earth is going on. I don't know what the titles are in Japanese; with "drifter," I was thinking of ronin, but I guess the actual title is "nagaremano," whatever that means. Anyway, script or no, the color in that movie is exceptional, no doubt.

And Los Angelino video clerks are the hardest to impress in America. None of them know my name, that's for sure. If you ever have an afternoon to kill, I recommend applying for a job at Rocket Video on La Brea--they make you take a movie trivia test that's a lot of fun (e.g., what section would you file Koyaanisqatsi under?). Anyway, congrats.

Just to clarify a bit of the translation: "nagaremono" means literally "the one who drifts", as in drifting in water. So, Tokyo Drifter is actually a very good translation of the title, it's even rare to get them SO well done from the japanese.

I haven't watched the Criterion release of the film, rather the english ICA VHS release, and, as far as my japanese goes of yakuza jargon, the subtiles are fairly OK.

Misato,

Thanks for the clarification -- yes; that's a good translation of the title then.

I recommend the Criterion release; the colors are fantastic.

Matt

I purchased and watched the DVD of Tokyo Drifter after first seeing it on TCM. I was quite satisfied with it except that the subtitles were of slightly lesser qualiy and some of the songs had no subtitled lyrics.

My personal Criterion Collection is nearing 80 movies strong now including Salo and this - and Branded to Kill are certainly among my favorites and both reward multiple viewings. You're going to pick up important tidbits and flashes of sheer brilliance on viewing 8 that were hidden to you on the previous 7 and I expect this is true into infinity. Brilliant cinema and well worthy of the Criterion treatment.

Once again, as in Branded To Kill, Suzuki lays a stylish veneer atop a mediocre foundation in Tokyo Drifter. I referenced Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy when writing about Branded To Kill, but the comparison is better suited to Tokyo Drifter where Suzuki’s color styling has a definite comic book flair. There’s also more than a little James Bond influence at work.

I agree there is more going on here than in Branded To Kill. However, the overriding theme I see revealed once you scratch this candy-colored surface is not so much a critique of Japan’s adoption of Western Culture post World War II as it is a variation on one of William Faulkner’s great themes: the clash of the modern world with the traditions and mores of the past and the turmoil visited on an idealistic young protagonist forced to live through that transition. Tetsu’s eventual rebellion against traditional concepts of loyalty and family and his simultaneous need for the security of those traditions literally set him adrift by movie’s end. Unfortunately, the B level script and mediocre acting don’t support the weight of that worthy theme.

Finally, I read the following recently in Steve Martin’s new novel, An Object of Beauty: “The theory of relativity certainly applies to art: just as gravity distorts space, an important collector distorts aesthetics.” While Criterion’s clear mission is to produce “a continuing series of important classic and contemporary films”, I wonder, with its increasing cachet and renown as a collector of films, does the Criterion label distort our perception of films merely by adding them to its collection?

Really great post, Thank you for sharing This knowledge.Excellently written article, if only all bloggers offered the same level of content as you, the internet would be a much better place. Please keep it up!

Post a Comment