High and Low, 1963, directed by Akira Kurosawa, written by Eijirô Hisaita, Ryuzo Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa, and Hideo Oguni, loosely based on Hayakawa Shobo's translation of Evan Hunter's novel King's Ransom, which Hunter wrote under the pen name Ed McBain. Now those are some complicated writing credits.

A space alien who knew nothing about film history and decided to learn it by watching the Criterion Collection would come to the conclusion that Toshirô Mifune was one of the best known actors in the world. He's been in five of the twenty-one movies I've watched so far: Seven Samurai, Musashi Miyamoto, Duel at Ichijoji Temple, Duel at Ganryu Island, and now High and Low. Don't get me wrong: I love Toshirô Mifune. But Criterion loves him even more.

The other four movies I've seen Mifune in are all period pieces where he plays a samurai. So it's kind of a shock to see him in a three-piece suit. He plays Kingo Gondo (Douglas King in the original novel), a wealthy shoe executive (no, really!). The premise is great; Gondo has a chauffeur whose young son is friends with his son. At the beginning of the movie, Gondo has borrowed against all his assets for a complicated business scheme whereby he will gain majority control of the company he works for. So he has a great deal of cash, all of it earmarked for saving his job and crushing his business rivals. Unfortunately for Mr. K., just as he's dispatching a junior executive with the money to make the stock purchase, he receives a phone call from a man who says he has kidnapped his son. He wants 30 million yen, of the 50 million Kingo has just pulled out. Kingo and his wife decide to pay it, and Kingo says that no amount of money is too much to pay for his son's life (he doesn't say this to the kidnapper, but he does say it in his chauffeur's hearing). Just then, Kingo's son walks into the room. Guess which chauffeur's son the kidnapper has grabbed by mistake? Guess who is suddenly much less willing to put up the ransom?

The first forty minutes or so of this movie are very tightly constructed. Kurosawa keeps everything in the same few rooms of Kingo's house (you could do this part as a play). I'd love to read an English translation of the screenplay because this part of it is a model of narrative compression. Some of the phone conversations between Kingo and the kidnapper are played out on screen (with police officers running everywhere trying to get a trace on the call, &c.). Some of the conversations you only hear as tape recordings when the police are playing them back, discussing them later. There's not a wasted second. And the sequence where Kingo pays the ransom (it takes place on the bullet train) is a wonderful set piece.

Unfortunately, after the Kingo pays the ransom (under protest) and the kid is returned, the movie kind of falls apart for me. The rest of the movie is about the police trying to get Kingo's money back as his world falls apart. It's all right, but without the ticking-clock of the kidnapped kid, it doesn't work as well. And some sequences didn't work for me at all: there's a long police procedural scene that falls flat. Structurally (and here I mean the internal structure of the sequence, not how it fits into the movie), it's a good idea; they have an intelligence briefing covering different investigative routes the police are taking. As each cop describes the lead he's been following, Kurosawa cuts from the briefing room to the cops investigating. It's not quite Law and Order, but it's the same focus on police grunt work that's made Dick Wolf a very rich man. But the sequence is fifteen minutes long and feels like it's an hour. What's more, none of the leads they're following pan out. So you get a good feeling for unrewarding police work, I suppose, but it totally kills the momentum Kurosawa has built up to that point.

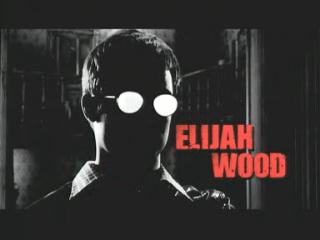

The end sequence is interesting; the camera follows the kidnapper through the slums of Yokohama as the police close in (it's actually a little more complicated than that). The killer doesn't get any dialogue here, and he wears mirrored shades. Which kind of reminds me of this other movie I saw the same weekend. Let's compare:

Akira Kurosawa's High and Low

Akira Kurosawa's High and Low

NOT Akira Kurosawa's High and Low.

Of course, Kevin looks that way in the books, so I guess Frank Miller is more the person who did the ripping-off. But it's even the same haircut. The stills don't do the similarity justice, because you can see an actual reflection in the glasses. A lot of the time in High and Low, the kidnapper is lit so the lenses are just as white as Kevin's in Sin City.

Some of the stuff in the "Low" section of the movie is really bizarre; there's a scene where the kidnapper pulls off a big heroin deal while frantically go-go dancing with his dealer (again, no dialogue). And there's a surprisingly scuzzy scene in a house full of heroin users. But there's nothing as tight as the first forty-five minutes in the movie's later scenes.

One more thing. Towards the end, I was expecting one more twist (Kingo set himself up! The police are in on it! It was all a dream!) and it never came. I don't think the movie really needed it, but it occurred to me how much I've been conditioned to want one last, overwhelming twist. I think a lot of scripts sell these days because they've got that, whether it fits the movie or not. Exhibit A is The Upside of Anger, where the twist betrays everything the movie has spent so long getting the audience emotionally involved with. But you can bet that people reading the script didn't ask whether the twist made sense for the movie so much as they said to each other "Twist! Buy! Buy! Buy!"

Random:

- Only one random fact. As you can see from the stills above, High and Low is in 2.35:1. This aspect ratio first appeared in 1953 and was called, in its original incarnation, Cinemascope. In Japan, it was called"Tohoscope." Tohoscope! For other names for widescreen film formats, see here. My favorites: Super Technirama 70, SuperTotalscope, and best of all, Warwickscope. Because nothing says "widescreen grandeur" like "Warwickscope!"

6 comments:

I think your comparison of High and Low to Sin CIty misses the artistic point of the glasses reflection in both. In High and Low, the reflection relates to the opressing heat of the city. It, together witht he other elements that suggest heat helps to convey the sense of grit, and wear of Japan and its people after the war.

In Sin Cith the effect is used more to mask Kevin's identity to imply that he's anonymous i.e. the boy next door. It also has the effect of block his eyes (the windows of the soul). For he is soulless, he has to feed on souls to sustain himself. It is only after we learn more about Kevin's character that his eyes are shown to us. Not so in High and Low.

I feel you should engage in a more healthy study of Akira Kurosawa's work before attempting to tackle the symbolism, and style of his films. You minor comparisions to predominantly unrelated films does both movies injustice.

AZ,

You make a good point about the way Kurosawa and Rodriguez *use* the glasses on their killers and in both cases I agree with you. But I have to disagree if you think that there's no relation in the images themselves. I wouldn't suggest that the killers are thematically linked (or that _Sin City_ tells you anything interesting about _High and Low_), but I do think the visual is a lift. That said, it's a minor point, and it's on the site only because I saw the two movies in a two-day period. What interests me most in _High and Low_ is the strange way Kurosawa lets all the tension he's built up in the first half of the movie evaporate once the kidnapped child is returned. I just finished watching _M_ today (and, speaking of lifts, the police procedural section of _High and Low_ takes a lot from it). Anyway, to me, part of what makes that section work in _M_ but not in _High and Low_ is the audience's understanding that Lorre will kill again if not caught. That's missing in _High and Low_. Anyway, I'd be interested in knowing what you think.

I'm not sure why AZ was so snotty; the first thing I thought when I saw "High And Low" last night was "Boy, that looks just like Kevin in Sin City: same glasses, same reflection effect, same hair, same blank expression." And that's how I found this blog entry.

I find it completely believable that Frank Miller, in crafting his gritty crime-ridden city, might borrow from a gritty Kurosawa crime movie. Yes, it might be to different effect, but I would find it hard to believe if Miller didn't admit that he at least drew inspiration from Kurosawa.

Yeah; I made the mistake of posting something announcing this project on the Criterion Collection Forum around the time of this post, and I got a lot of snotty comments, both on the forum (the thread this was on was deleted), and on my blog immediately after. In defense of the people who wrote about how terrible my blog was, the early posts are pretty terrible; I often think about revising them but suppose it's better to just plow forward.

Either this project is having the intended effect of making me a better audience or Akira Kurosawa is so good that he forces you to notice things you’ve never noticed before. Or maybe it’s a little bit of both. Whatever the explanation, I was immediately impressed by the widescreen compositions throughout High and Low, how Kurosawa fills the screen and what those spatial relationships tell us about the story and the characters. I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have consciously recognized any of this a year ago.

The apparently effortless transitions from one widescreen composition to the next also made an impact and got me to thinking that film really is a three-dimensional art form: you’ve got the two dimensions of the picture plane, plus time.

My first viewing of the film was on a flight from Tampa to Newark and I only got as far as the child’s recovery by the police, the ending of the “high” section. And I loved it, couldn’t wait to see the rest of it. But I agree with you that the second half, while still enjoyable, can’t compete with the first. I recently saw Full Metal Jacket, another admirable film composed of sharply distinguished acts. This type of film structure (as well as the omnibus film) never entirely satisfies as a whole because no matter how good the individual parts, the structure itself invites internal comparisons and a divisive sort of critique. In any competition, a tie is the least likely outcome, and therefore one part will almost always resonate more than another with a viewer. If I were a writer, I’d carefully consider the warning signs before entering these waters.

Matthew -

Great blog, with terrific insights. I am now convinced (after watching HIGH AND LOW in its entirety for the third time) that there is a brilliant twist: The kidnapper is in actuality a bastard son of Gondo.

From this perspective, suddenly many (but I admit, not all) details in the film make sense, and in fact gives the film much greater impact. The kidnapper's motive is driven from the rage of living a meager life, and having to look at his father's lavish house on the hill every day. In anger and revenge, he attempts to kidnap the son he should have been.

This also explains why Gondo would even consider visiting the kidnapper in prison, and his somber demeanor during the incredibly subtle ending. In the final sequence, there are more hints, including the kidnapper's mention of his mother's suffering, said in a way that suggests that Gondo would be familiar with the woman. There is also the ghostly mirroring of their faces in the separating glass.

I would guess that a subject such as a bastard son would have been a taboo movie subject in 1963 Japan, but the overall subject matter falls in line with Kurosawa's career obsession with Father/Son relationships gone wrong.

Or, of course, I may just be reading too much into all of this; any rebuttals or critiques of my theory are very welcome.

Thanks,

Dennis

Post a Comment