Big Deal on Madonna Street, 1958, directed by Mario Monicelli, screenplay by Agenore Incrocci, Furio Scarpelli, Suso Cecchi D'Amico, and Mario Monicelli, story by Agenore Incrocci and Furio Scarpelli.

In literature everyone understands the problems of translation. You only have to glance at a few sentences of Stuart Gilbert and Matthew Ward's respective versions of L’Étranger to understand how much of a mark the translator leaves on a text. New translations can be literary events in their own right. We understand, when it comes to books, that the original language is always preferable to any other version: a true literary polymath reads Milton in English, Tolstoy in Russian, Proust in French, and Shakespeare in Klingon. And yet, even though I'd wager that in an average year most English-speakers encounter many more non-English films than books, (with one major exception), film translation gets short shrift. It's not just neglect; there's a real difference in the way we think about language in films. I'm no exception—every word of German I know, I've learned from video games (Schnell, schnell! Die Amerikaner!). But when I say I've seen The Lives of Others, I mean it in a different way than when I say I've read Goethe.1 This isn't entirely irrational: film isn't quite so at the mercy of language as a Pynchon novel. But it's odd that film translation is so ignored: besides the occasional DVD package boasting that the subtitles have been "improved" (How? By who?), I don't know any cinephiles or critics who pay much attention to what's going on when a film is translated.

That's not to say no one pays attention. Studios care because they have to; at New Line I got to see the post-production department prepare a sort of annotated version of each film for use by translators. This consisted of a large binder in which every line of dialogue was dutifully transcribed, and any idiomatic expression explained within an inch of its life.2 It's easy to imagine when watching a foreign film that, assuming the translators were working from a sufficiently detailed binder, the English subtitles provide a functionally identical experience. And for, say, The Raid: Redemption, this might actually be true. But flip the problem around and this position immediately seems absurd. If you were writing Italian dialogue for Transformers, maybe you could pull it off. But what happens if you end up translating Fargo? You might be able to go through the script, line by line, and capture the literal meaning of each sentence. But half the point of the dialogue is the strange Minnesota diction ("a no-rough-stuff-type deal," or this exchange). There's no Italian sentence that conveys exactly the same meaning as "So I says, 'Well, that don't sound like too good a deal for him, then.'" And that's before you add the problem of accents. In the actual event, the Italian translators for Fargo seem to have ignored the accents and regionalisms completely: compare this to this. How much of the feeling of the scene is lost simply because Jerry Lundegard's Minnesota "Yah" is reduced to "Si?" I don't think there's a way to translate the experience a native English speaker has while watching Fargo into any other language. At least, not without taking an approach like Nabokov's translation of Eugene Onegin:

I had to decide between rhyme and reason—and I chose reason. My only ambition has been to provide a crib, a pony, an absolutely literal translation of the thing, with copious and pedantic notes whose bulk far exceeds the text of the poem. Only a paraphrase "reads well"; my translation does not; it is honest and clumsy, ponderous and slavishly faithful.

Which is basically the experience you'd have if the subtitles showed everything in the studio translation binders. But as much as I'd like to watch, say, the Nabokovian subtitle edition of Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle, I'm not sure it would be a big hit in movie theaters.

All of this is an roundabout way of saying that Mario Monicelli's Big Deal on Madonna Street is a very different film for a native speaker of Italian than it is for an English speaker. Before someone shows up in the comments to play Nabokov to my Edmund Wilson, let me be clear: I am not that native speaker of Italian. But I know there's a lot of information about the speaker's class and upbringing encoded in "Avvocà, io bisogna che esco—che esco subbitu!" that's not present in "Counselor, I gotta get outta here, now." And I'm afraid I don't see any reasonable way to communicate all of the meaning of the dialogue to viewers who speak other languages.

Which is not to say that Big Deal On Madonna Street should be the stone under which the whole rotten edifice of film translation crumbles. For one thing, I would hesitate to hang too much of a case for anything on a movie this light. It's not as if there are that many crucial subtleties or lost emotional resonances in the dialogue; the film opens with a completely bolluxed theft of a Fiat 1400 and ends with a meticulously choreographed heist that yields only a pot of leftover pasta e ceci. Nevertheless, virtually every character is a distinct Italian regional stereotype, from Memmo Caruteno's wildly gesturing Roman:

To Tiberio Murgia's Sicilian peacock.

To Carlo Pisacane's whatever-the-hell-he's-supposed-to-be. He speaks Emilian and is always nibbling on any food he can get his hands on, but I've never heard that Emilians were stereotypically associated with gurning contests.

But in a film in which a great deal of an Italian audience's enjoyment comes from Boss-Hogg-level regional caricatures, the only part which makes it to the subtitles is a single line, the Sicilian's belief that the Abruzzese are citified northerners. Non-Italian speakers will probably notice that one character's attempt at a northern Italian accent is terrible, simply because his voice suddenly sounds cartoonish. But again, that's not in the subtitles; that entire level of meaning just doesn't make it to English.

Which is not to say that there's not a lot to enjoy, no matter what language you speak. Big Deal on Madonna Street, even without the accents, is one of the funniest heist spoofs ever made, and its success on this level is entirely translatable. The plots of these sorts of films are all more or less interchangeable: learn about the big score, build a team, planning, execution, MISADVENTURE. Usually, you're hoping for exceptionally charming or interesting people to make up the team—and Big Deal On Madonna Street has that in spades. But if you or I made a heist spoof with the same actors playing the same characters, it would probably not be as funny. Part of the reason it's as good as it is is that Gianni Di Venanzo's cinematography plays it completely straight. You'll have a hard time finding a better looking noir than this.

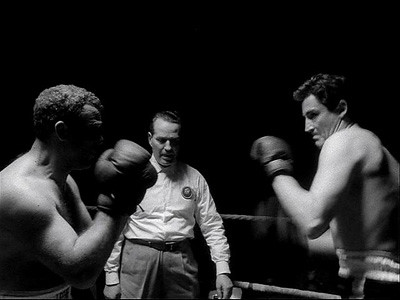

That's Tiberio Murgia again on the far right; the others are Rossana Rory, Renato Salvatori, and yes, Marcello Mastroianni. They're attending a boxing match that perfectly illustrates the way the film works: the boxers leave their corners in a shot that's as inky as the opening of The Big Combo, complete with Scorsese-style flashbulbs.

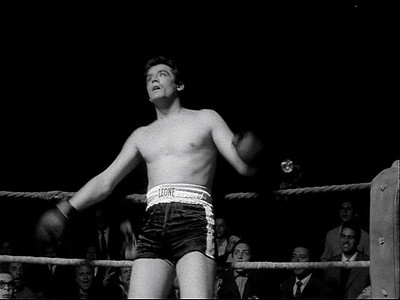

The mood lasts for less than two seconds before Vittorio Gassman takes a punch to the face and goes down crosseyed like Chaplin.

That's Big Deal On Madonna Street in a nutshell: very serious cinematography in service of very silly jokes. Mario Monicelli's second secret weapon is Rome circa 1958, which lends a certain gravitas to the proceedings by virtue of being unrelentingly depressing.

It isn't neorealism, but it lives in the same crappy neighborhood.

The exceedingly low ambitions of the hapless burglars at the film's center fit right in with the locations. As far as the team goes, Marcello Mastroianni is the standout, as a photojournalist who's fallen on hard times and had to sell his camera. His wife's in prison for smuggling cigarettes, which means he's planning a criminal conspiracy while babysitting.

The rest of the gang puts him in charge of shooting surveillance footage of the pawn shop they're planning on robbing, and the film is worth seeing solely for Mastroianni's boyish enthusiasm at the blurry, juddery footage he proudly screens for them. At least half of it is "test shots" of his kid.

There's also a nice part for Totò, who is something of a minor diety to Italians.3 He's not on-screen much—although he got largest billing on the original Italian posters—but he does the right kind of celebrity cameo (cf. Keaton in Sunset Blvd.), not drawing too much attention to himself or stealing scenes. He just puts as much realism as possible into the part of a master safecracker whose set of tools includes a cheese grater.

The film also offers the opportunity to see both Carla Gravina and Claudia Cardinale at the very start of their careers. Cardinale, playing the sister the Sicilian is keeping locked up before her wedding, is all of 20 years old. You can probably see exactly where this particular plot thread will go:

Gravina was still younger; she couldn't have been more than 16 during filming. She gets to do a sort of live-action version of "American Girl in Italy."

It's a great cast, and they're what sell the movie, because the outcome of Big Deal on Madonna Street is never in much doubt. As in any heist film, things will go wrong, the gang will splinter, and by the end, no one's lot will be much improved. Those are the demands of the genre. But the charm of Big Deal On Madonna Street is that success or failure doesn't seem to matter all that much to the characters. They go through the motions of a heist, but you wouldn't call them criminals, exactly. It's more accurate to say that they're always, always working an angle, the more improbable the better. And when their schemes fail, as they inevitably do, they're basically content, because what're you gonna do? Like I said: some kinds of Italian, they don't make subtitles for.

Randoms:

- Many of the actors are dubbed by other actors who spoke the appropriate dialects. Tiberio Murgia was Sardinian, not Sicilian, and ended up being dubbed by a Neapolitan. Carlo Pisacane, who actually was Neapolitan, was dubbed by a Friulian in Emilian. Memmo Carotenuto speaking his own Romanesco was the exception, not the rule. But by far the oddest bit of dubbing was Rossana Rory, who was dubbed by Monica Vitti. Yes, that Monica Vitti.

- The film's plot follows Rififi closely enough that the working title was apparently Rufufu.

- Through a complicated sequence of events, Totò managed to be the heir to two noble families and all their inheritable titles. Which means his full name was, honest to God, "Antonio Griffo Focas Flavio Ducas Komnenos Gagliardi de Curtis of Byzantium, His Imperial Highness, Palatine Count, Knight of the Holy Roman Empire, Exarch of Ravenna, Duke of Macedonia and Illyria, Prince of Constantinople, Cilicia, Thessaly, Pontus, Moldavia, Dardania, Peloponnesus, Count of Cyprus and Epirus, Count and Duke of Drivasto and Durazzo." Gods, stand up for bastards!

1For one thing, when I say I've seen The Lives of Others, I'm not lying.

2"The Gift was a film directed by Sam Raimi in 2000. Katie Holmes is an actress who appeared in The Gift. "Titties" is a colloquialism...

3Chaplin may be the Chaplin of the Zulus, but Totò is, now and always, the Chaplin of the Italians.