Coup de Torchon, 1981, directed by Bertrand Tavernier, screenplay by Bertrand Tavernier and Jean Aurenche, from the novel Pop. 1280 by Jim Thompson.

One of my favorite types of novel doesn't really have a name, but if it did, it would be something like "books with possibly unreliable narrators who are morally reprehensible but can also be quite charming, because, after all, they're the narrator." At the top of the list are Lolita and Money, of course, but below that things get muddier. It's not enough for the narrator to be morally compromised. It's not even completely necessary: The Catcher in the Rye and Pale Fire both fit the bill, despite the fact that neither Holden nor Kinbote are particularly evil. And despite their horrific narrators, neither American Psycho nor To The White Sea qualify. The difference is that Humbert Humbert, John Self, Holden Caulfield, and John Kinbote care what the reader thinks of them; Patrick Bateman and Muldrow do not. Above all, novels of this sort are cases for the defense.1

And as it happens, cases for the defense are exceptionally difficult to adapt for film. With a very few exceptions, film has an implied third-person narrator that isn't known for lying or being charming, so it's hard to capture the tension between style and content that is at the heart of these works. The most successful adaptation of this type is Goodfellas, and it's worth noting how much formal trickery Scorsese needs to get there: freeze-frames, voiceover, self-consciously dazzling tracking shots, characters directly addressing—or shooting—the camera... it's dizzying. Unless you're Martin Scorsese (even if you're Kubrick), you'd probably do better to leave this kind of story alone.

Unless, of course, your goal is to make a film that's quite different from its source material. Fortunately, that seems to have been Bernard Tavernier was up to when he set out to adapt Jim Thompson's Pop. 1280, a black valentine of a pulp novel that fits comfortably into the tradition of cases for the defense. The first sentence of the novel is "Well, sir, I should have been sitting pretty, just about as pretty as a man could sit," and the rest follows suit: conversational, friendly, and addressed to that "sir." Thompson's narrator is Nick Corey, a do-nothing sheriff of a do-nothing southern county. He doesn't have the eloquence of Humbert Humbert or the mad energy of John Self, but he's charming and funny and wants the reader to like him. And we do like him, which makes it increasingly uncomfortable as we realize just how far off the rails he's gone. Although there are plenty of scenes in the novel that would work well on film, most of the work depends on the tone, in passages where nothing is happening except for whatever's happening in Corey's head.

So Pop. 1280, on its face, doesn't seem well suited for film to begin with. It's an especially bad idea for a French director to attempt it; the American South is difficult enough for Americans to get right on film, never mind non English-speakers. Bernard Tavernier explains in one of the DVD extras that he'd tried for years to figure out a way to film Pop. 1280 without success. Eventually, he found an elegant solution to the novel's setting: rather than trying to capture the details of a culture he didn't know, or move the story to France and make key plot points implausible, he set it in French West Africa, in July of 1938. That gave him two things the story needed: a despised racial underclass and plenty of open space. But it's still a novel whose formal qualities are ill-suited to film. Nick Corey can describe the most appalling things in ways that minimize his own involvement, even make them funny; Lucien Cordier (Nick's name in the film) can not. Tavernier's solution to this is surprising and impressive: he simply embraces the fact that Cordier's actions will seem bewildering and horrifying and runs with it. The result is a film quite different in tone, where black humor has been replaced with existential dread.

That doesn't mean that Tavernier's main character, whose name has been changed to Lucien Cordier, is completely devoid of Nick Corey's lackadaisical charm. Tavernier cast Philippe Noiret, who trades on the same kind features that would later serve him so well in Cinema Paradiso and The Postman. With a little help from the costume department (that hat! that shirt!), Noiret presents himself as a kind of holy fool. Here, he's just realized that the hat he is looking for has been on his head all along.

The costumes actually do a surprising amount of the heavy lifting, placing the early scenes in the world of comedy. Here are Stéphane Audran and Eddy Mitchel as Lucien's wife and her mentally challenged lover, in what must certainly be the most cartoonish flagrante delicto ever.

The curlers are nice, but it's the tufted slippers that push Audran's outfit completely over the edge. Isabelle Huppert is equally good as Lucien's mistress, Rose (one of the few characters who keeps her name from the novel).

Casting Isabelle Huppert is always a good idea, but it works especially well here: Rose's avarice, lust, and rage, filtered through Huppert's childlike frame, produces something like a female version of Hop-Frog. So some of the humor is still there; but Tavernier lets it go sour much faster than Thompson does. Consider one of the changes Tavernier and Aurenche make to the novel's chronology. One of the ways Nick Corey gets his revenge is more of a prank than a crime. Corey is bothered by the smell of an outhouse near his home. Unable to get the city to move it, he resorts to cutting halfway through some of the boards so that one of the town's dignitaries falls in the shit (and immediately demands the outhouse be removed and filled in, solving Nick's problem). The scene's still in the film:

And it's as slapsticky as it is in the novel. But while Thompson has this happen in the first twenty pages, Tavernier puts it after we've seen Cordier murder three people. We're expecting Lucien to pull out his revolver and start gunning people down at any minute, which makes the whole thing a lot less hilarious. It's too late for slapstick to ingratiate Lucien with us.

Making that scene really uncomfortable for viewers is part of a larger aesthetic choice not to minimize or excuse Cordier's murders, the way Thompson's narrator does (at least early in the novel). Here's how Nick Corey tells the reader about murdering two local pimps in cold blood, using the sound of a steamboat whistle to cover the gunshots:

"Good night, ye merry gentlemen," I said. "Hail and farewell."

The Ruby Clark whistled.

By the time the echo died, Moose and Curly were in the river, each with a bullet spang between his eyes.

I waited on the little pier for a minute until the Ruby had gone by. I always say there's nothing prettier than a steamboat at night.

Spang! On film, there's only so much you can do with this. You could try to render Nick's lacuna by cutting to the steamboat whistle, then back to the pimps dead in the river, but since the audience isn't thinking of the camera as a first-person narrator, we wouldn't credit that gap to Nick. And it's an inescapable fact that although a description of a body with a bullet "spang between the eyes" is funny, an image would not be. Tavernier just goes ahead and shows the pimps getting shot:

It's still kind of funny: those ridiculous suits, the jacket on fire, but it doesn't have the same tone. In Thompson's version of the story, the build-up to nihilism is gradual; it's the second to last chapter before Nick Corey goes big and gives us his vision of a sick, dying universe, of "all the sad and terrible things that the emptiness had brought the people to." Tavernier goes full apocalypse in the very first scene: a complete solar eclipse.

"I thought it was Judgment Day,"2 says one of the characters. Well, there's no eclipse in Pop. 1280, nor was there one in July of 1938, so someone's behind it. The line is repeated during another scene found in the film but not the novel, a sandstorm during an outdoor film screening.

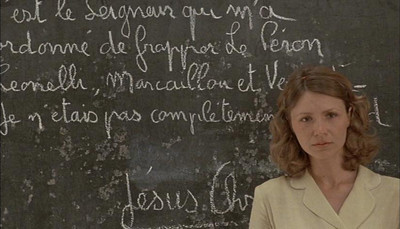

Even suggesting the possibility of judgment puts Coup de Torchon in a different moral universe than Pop. 1280, and once you realize that, his other decisions fall into place. Thompson's characters are monstrous from beginning to end, but Tavernier's characters are monstrous in a way that depends on them being in French West Africa, a place where, as Lucien puts it, good and evil get rusty. You can see this pretty clearly the way he treats Anne (Irène Skobline), a schoolteacher who has just arrived in town. When she first appears, she seems like a civilizing influence on Lucien, but she gradually becomes more complicit in his crimes. There's a lovely scene where she tells her illiterate students that a confession Lucien has scrawled on the blackboard is actually "La Marseillaise."

Her analogue in the novel is as petty as Rose, from start to finish; there's no decline. So why do Tavernier and Aurenche go out of their way to build in a fall from grace? People criticize Coup de Torchon for its nihilism, and it's true that most of the characters are nihilists; but not Lucien. As he tells Rose, his mission is to "just help people to reveal their real nature." It just so happens that he's in a time and place where a whole lot of people are just about to reveal their true natures. The film is set during the summer and early fall of 1938; one of the last scenes is a celebration of the signing of the Munich Accords. Which is to say it's set during the last few months Europeans could pretend they were going to resolve their disagreements without murdering each other. Which is to say it's set during the last few months the French could plausibly be said to have an empire. Which is to say the film's characters have a dim sense of approaching doom that the novel's characters do not. The Netflix sleeve for this one reads, "Out of the blue, the ostensibly brainless Lucien decides to seek vengeance..." But it's not out of the blue, in French West Africa, in 1938. They'll think it's judgment day.

Randoms:

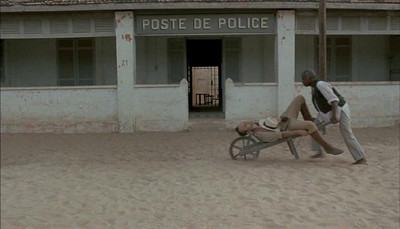

- The look of the film is perfect throughout. It's sort of an anti-Out of Africa; Tavernier's Africa has no sweeping vistas or exotic wildlife; it's as faded as Lucien's shirt.

- He also gets a lot of mileage out of using a Steadicam in scenes where other people might use a tracking shot; the camera swoops around its subjects in a way that suggests neither classical Hollywood film making nor any attempt at documentary style. It suits the film perfectly.

- Apparently American audiences didn't want to see a non-exoticised Africa, however: the American poster features a silhouette of spear-carrying tribesmen, and utterly fails to convey that this is a noir.

- Needless to say, there are no tribesmen in the film.

- Sometimes, producers are right. Tavernier's original vision for the film's ending went much bigger on the whole end-of-civilization theme, in a way that he now admits was probably not his best idea. He wanted to have the dancers at the celebration gradually replaced by dancers in military uniforms, then replaced by skeletons, then have apes dancing, to make some kind of point about the cyclic nature of history. Only he couldn't afford the uniforms or the skeletons, so he just shot it with the ape suits.

- I like to imagine the look on the producers' faces when they saw those dailies.

1The question of why I enjoy novels in which rat bastard narrators make pleas for clemency is left as an exercise for the reader.

2I think the literal translation of the line is "I thought it was the end of the world," which is rendered "I thought it was judgment day" in the subtitle. Same idea, though.