Spartacus, 1960, directed by Stanley Kubrick, screenplay by Dalton Trumbo, from the novel by Howard Fast

When most actors discover they didn't get a role they wanted, they react like you or I would: by driving to Las Vegas and spending the rent money on blackjack and cocaine. But Kirk Douglas was never most actors. So when William Wyler gave the role of Ben Hur to Charlton Heston, Douglas decided he'd make his own sand and sandals epic, better than Ben Hur, staring himself and not Charlton Heston, and who wants to work with William Wyler anyway? For his subject, Douglas chose Howard Fast's fictionalized version of the Third Servile War, Spartacus. Perhaps Douglas recognized a kindred spirit in Fast, who, on finding himself blacklisted from publishing because of his refusal to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, published Spartacus himself. Like most projects started to compensate for rejection, Spartacus is self-consciously designed to proclaim its own greatness in every possible way. But it was made during the golden age of Hollywood epics, when the bar for films proclaiming their own greatness was very high indeed; Cleopatra wouldn't spoil everyone's fun for another three years. So how did Douglas signify to audiences that they were watching an epic?

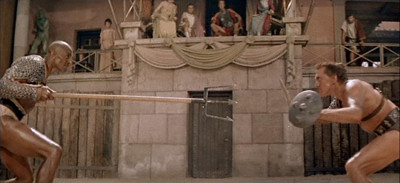

Start with the film stock. Part of the point of epic filmmaking is to make something that television can't possibly compete with, which means an very wide aspect ratio, projected on gigantic screens. Masked 35mm is the cheapest and easiest way to get the aspect ratio, but you're not even using the entire 35mm frame, so it gets grainy if you project it on too big a screen. Anamorphic 35mm uses the full frame and looks better—that's what widescreen filmmakers normally use today—but it's still not as sharp as you want if you're going to project it onto screens the size of small towns. So you've gotta go higher resolution, which usually means 65mm stock. Ben Hur—the production Douglas saw as his direct competition—was shot using a process called MGM Camera 65, which not only used a 65mm negative but an anamorphic lens on top of that, and produced what is probably the widest aspect ratio in commercial features: a 2.76:1 image. But 65mm film stock is ridiculously expensive, so Spartacus was shot using a different process called Super Technirama 70. Despite the name, Super Technirama doesn't require 65mm film stock. Instead, standard 35mm was run through the camera sideways, allowing for a wider aspect ratio that could still produce a good-looking 70mm print.1 Which is to say, a print where shots like this look like an army, not a failed experiment in Pointillism.

That kind of shot is what large-format film is designed for—you can see every dollar on-screen. And Spartacus lets you know with every frame that giant screens are the only way to see it; this was not shot with television in mind. Take the scene where Tony Curtis's Antoninus performs a magic trick for a group of rebel slaves. Kubrick opens with this shot:

A contemporary filmmaker shooting the same scene might use that framing as an establishing shot, but Kubrick stays on it for more than thirty seconds, following Curtis as he performs an entire magic trick. He only cuts closer when Curtis approaches Jean Simmons and Kirk Douglas, and even then the camera keeps its distance. It's true that long takes are still around, but look how little of the frame Curtis takes up, and keep in mind that the point of the shot is what Curtis is doing with his hands. There are ways to signify "epic" without using giant crowds.

I found it interesting to compare Kubrick's compositions with contemporary use of wide aspect ratios, more for what's missing than what's there. You won't find a shot in Spartacus that resembles this:

Or this, from a very different filmmaker the same year:

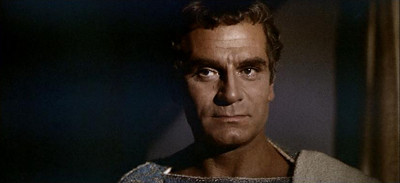

With a very few exceptions, Kubrick's close-ups show the actor's full head, as in this shot:

And, although there are plenty of wide-angle shots, you won't find anything like this:

Or this:

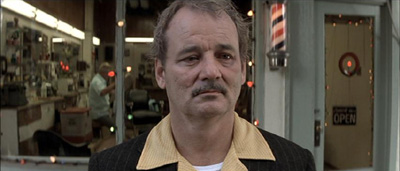

There are wide-angle medium shots, like this one:

But notice that John Dall is far enough back from the camera that his face isn't particularly distorted; compare that to Bill Murray's cartoonish face in the still from Rushmore (or pretty much any close-up in A Clockwork Orange). It's a different cinematic grammar, closer to classical Hollywood cinema than anything else of Kubrick's I've seen.

The camera movement is also atypical for Kubrick̬his previous film was Paths of Glory, in which the most striking visual images depend on tracking backward through the trenches—and of course, this is the man who would go on to photograph the corridors of the Overlook Hotel. But in Spartacus, the camera is pretty stationary throughout; most of the motion is panning, and limited examples of horizontal tracking. There most prominent exceptions bring us back to the "self-consciously epic" thing. There's a long shot of horsemen in a distant valley:

Which tracks back to reveal a watchman on the cliff above:

And then tracks further back to pick up Kirk Douglas on horseback:

From there the camera tracks horizontally as Spartacus rides through the camp. So Kubrick uses a track backwards to play with scale in a way that makes viewers painfully aware of what a gigantic production they're seeing. Then there's this sequence, after the climactic battle between the rebel slaves and the Romans:

The camera tracks forward over the bodies of the defeated slaves, slowly panning up to reveal that the carnage goes as far as the eye can see. As with the other sequence, the tracking is used to for an effect of scale: you wouldn't believe how many corpses the Romans produced! And if this shot reminds audiences of another epic, then so much the better. So there are some examples of three-dimensional movement in the film, but I thought it was striking how stationary the camera remained, and how self-consciously horizontal many of the compositions are. It doesn't get any more wide-screen than this:

In short, it doesn't look anything like a Stanley Kubrick film. But this was an atypical production for Kubrick, the only one he didn't have near-complete control. He was brought in a week into shooting when Douglas fired Anthony Mann, handed a copy of the script and given a weekend to take over the production (his offer to rewrite the script was summarily rejected). Spartacus was a smart career move for him, since he hadn't made a film in two years and had never run a production of this size, but it's clear his heart wasn't really in it.2

Which makes it sound like Spartacus was doomed to mediocrity by its troubled production history, but it does has its pleasures. Mostly, they come from the last ingredient for an epic: epic casting. There's no question that Douglas is the star (and plenty of shots of him looking noble):

But you can't make a really big movie with only one star; convention demands that such a film be cast within an inch of its life. So for every scene where Kirk Douglas speechifies about freedom and slavery, there's a matching scene where Lawrence Olivier, as Crassus, is sinister and sly.

Better yet are Peter Ustinov and Charles Laughton, who often seem to be checking in from a different film, a light comedy about lust and gluttony.

As it happens, that isn't far from the truth: Ustinov apparently rewrote most of their scenes, much to Dalton Trumbo's dismay. So although it may not serve the rest of the film well, the scenes with Ustinov are better than the ones with Douglas. Ustinov won an Oscar for his performance; Douglas wasn't even nominated.

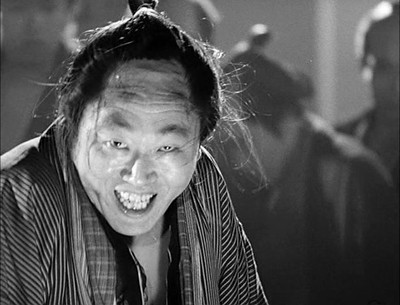

That isn't entirely fair to Douglas: it's always more interesting to watch vice than virtue. But the difference between the Roman scenes and the scenes with Spartacus is so great that I think it points to the film's biggest problem: Spartacus doesn't have any flaws. After the film's opening scenes, in which Spartacus is basically feral, he stops making mistakes. There aren't any arguments among the slaves about what to do, there aren't any power struggles between Spartacus and his lieutenants, there aren't any tactical errors. There are flickers of life when Herbert Lom appears as an untrustworthy pirate:

But for the most part the scenes with the slave army are a cinematic essay about how great freedom is in general, and how great Spartacus is in particular. Any actor would have a hard time making that kind of pablum interesting, but Kirk Douglas is particularly ill suited for it. I've always thought he was better cast as a villain than as a hero; he has a hail-fellow-well-met quality that only shines for me when it's backed by malice. But malice is beneath Spartacus, and that's the problem. In his effort to outdo Ben Hur, Douglas ended up playing a character who was too heroic to be interesting. Still, he's undeniably epic.

Randoms:

- The commentary track on the DVD is fascinating, most of all for novelist Howard Fast's contributions, which run the gamut from passive-aggressive to positively venomous. Fast was originally hired to write the screenplay, then fired when it became apparent that his version of the film would contain more speeches than action. You can predict what he'll think of any given scene by checking how closely it follows his novel. Two examples:

This, for example, is not in the book. I don't know that it adds very much. If I remember, the dialogue is rather silly.

I highly recommend listening to the whole thing.

. . . .

This is a brilliantly done scene; it is lifted out of the book almost in its entirety, and well directed, and well done.

- Spartacus gets a lot of credit for the political act of hiring Dalton Trumbo and crediting him under his real name, helping to break the blacklist. And it definitely deserves that praise. But it's also worth noting that the battle scenes were filmed in Franco's Spain, where the production paid the government directly for the uses of the Army. So Spartacus is one of those symbolically-upholding-freedom-while-paying-cash-money-to-dictators productions. Like U.S. foreign policy!

Update: Robert Taylor has thoughts in a similar vein about the film here.

1The difference between 65mm stock and 70mm prints is the 5mm section used for the film's soundtrack.

2As Kubrick put it years later, "I don't know what to say to people who tell me 'Boy, I really loved Spartacus.'"