The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972, directed by Luis Buñuel, written by Luis Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière.

It's a truism that the 1970's were a golden age for mainstream recognition of difficult films. But if you want to really demonstrate to someone exactly what that means, don't sit them down in front of Mean Streets or The Conversation. Put in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and tell them that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—the same stodgy, conservative voters who chose Ordinary People over Raging Bull just a few years later—named The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie Best Foreign Language Film of 1972. It's impossible to imagine it even getting distribution today.

If you had to, maybe you could sell it with a clever bait-and-switch trailer, because stripped of tone and context, the onscreen events don't seem that far from, say, The Secret in Their Eyes. Consider the following plot points. The minister of a corrupt South American country uses his diplomatic pouch to smuggle cocaine. One revolutionary is dragged off by the secret police; another is tortured with an electrified piano. A young boy poisons his stepfather's nightly glass of milk. A priest gives a dying man absolution and then shoots him in the head with a shotgun. One dinner party ends with a duel, the next with the guests lined up against the wall and machine gunned. And there are more dreams-within-dreams than Inception. But because this is Buñuel, the only thing anyone wants to talk about are their dinner plans.

It's hard to imagine for a film with so many events, but The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie doesn't have much of a plot—or to be more precise, there isn't any causal relationship between one event and the next. To be clear, Buñuel does have something on his mind here: no matter how loosely connected and absurd the film's sequences may be, they are all thematically linked. Each section of the film is built around a failed attempt by the main characters to eat dinner together, and each meal is interrupted by something good members of the striving classes don't discuss at the table: death, sex, religion, crime, the military. And, of course, South American death squads.

Strivers denying their animal natures—that's the kind of thematic material that could quickly become boring and pretentious, especially in a film as uninterested in Hollywood narrative conventions as this one. But Buñuel manages to avoid this with a remarkably deft comic touch and precise control of the film's tone, which is never strident or humorless (nor, on the other hand, too forgiving). Consider the scene where Don Rafael Acosta—representative of South American kleptocracy Miranda—pulls out a sniper rifle and starts taking potshots at a young woman out his office window.

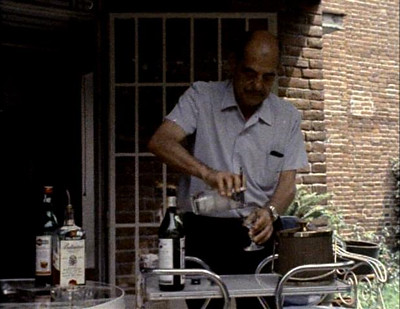

Fernando Rey plays Acosta; the other bourgeoisie in that shot are Jean-Pierre Cassel (Vincent's father) as Henri Sénéchal and Paul Frankeur as M. Thevenot. In a pretentious version of Discreet Charm, Sénéchal and Thevenot would be unmoved, or would enthusiastically help Acosta out. In Buñuel's version, they're a little put out and concerned, but only a little—they're certainly not going to make a fuss about it. That's the tightrope Buñuel successfully walks in scene after scene: as horrible as his characters are, he's not unsympathetic. After all, how can you hate people who make such wonderful Martinis?1

A little sympathy is the difference between an effective satirist and a strident bore, and the film as a whole is a useful reminder that the opposite of "funny" is not "serious." Between failures, social humiliations, duels, murders, gardening, and garden variety adultery, Buñuel repeatedly cuts to shots of the principal cast walking down the road through open countryside.

The film's Wikipedia article says that in these shots, the characters are lost and wandering, but I don't see it. They're always moving at a good clip, lapping the miles, never moving backward, devouring the future like locusts. No one in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie would ever see The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Guess who's running the studios?

Randoms

- I'm going to be much less wordy going forward, at the cost of being less thorough. The whole point of this project, for me, was to see a lot of great movies, and one a month isn't going to cut it. So I'm certain there will be many things I leave out (nothing here about the film's women, all of whom are marvelous—especially Stéphane Audran's steely hostess? For shame!) Perhaps we can discuss things in more detail in the comments.

- The DVD features an excellent documentary about Buñuel's life and work, including his early years bumming around with Dalí and Garcia Lorca. Most interestingly, there's a short film called El náufrago de la calle de Providencia, which has footage of him enthusiastically explaining how to make various cocktails. Apparently he appreciated a good Martini just as much as Thevenot.

- It seems that Cooper Black was the Trajan of 1972 (or at least the Futura). It's in the opening credits of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, and also John Huston's marvelous Fat City. Which is kind of strange if you're used to seeing it on iron-on t-shirts. Here's the strangely inappropriate title screen:

1Or claim to make wonderful Martinis, anyway; I didn't notice him shaking it to waltz time.