L'Avventura, 1960, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, screenplay by Michelangelo Antonioni, Elio Bartolini, and Tonino Guerra, story by Michelangelo Antonioni.

Film genres have observable lifecycles. Comedy has survived pretty much unchanged since L'Arroseur Arrosé, like those bacteria that have been alive since before the dinosaurs. Westerns are more like cicadas: they burrow underground for ten years or so, and just when you've forgotten they exist, they're suddenly everywhere. And then there are the mayflies: distinct genres that show up for a few years, have their moment, and end up smeared all over the windshield of history.

L'Avventura is the preeminent example of one of those windshield smears, where you'll also find Last Year at Marienbad, La Dolce Vita, and most of Antonioni's other films. They all share a sort of apocalyptic, exhausted ennui and feature characters who are miserable, wealthy, dissolute, and incredibly well-dressed. Their genre didn't stick around long enough to get an official name, but Pauline Kael called them "The Come-Dressed-As-the-Sick-Soul-of-Europe Parties," and that's good enough for me. They moved from groundbreaking to cliché to parody in record time: Kael was hailing L'Avventura in 1960 and condemning everything that followed by 1961. She and Andrew Sarris didn't agree on much, but they agreed on this: Sarris coined the term "Antoniennui." But no film can be held responsible for the worst excesses of its genre, and L'Avventura is truly a remarkable, unique achievement, innovative in narrative structure, visual grammar, and editing. And frame for frame, it's one of the most beautiful movies you'll ever see.

The film begins with a tracking shot of Anna, a sourfaced young woman played by Lea Massari, walking toward the camera, away from a villa. We hear her father lamenting the new construction smothering his villa, and then Antonioni cuts to a very long take of Massari and Renzo Ricci having an argument. The shot lasts 54 seconds, and the camera moves as they cross each other, but here's the most striking framing:

There's Antonioni in a nutshell: two people talking past each other without eye contact, meticulously staged and photographed. Notice how he's put Massari in front of the modern architecture her father was complaining about, while putting the older man on that great diagonal line toward St. Peter's: do you think one of these two characters is meant to represent modernity encroaching on the old order of things? Imagine you are the location scout asked to find a spot from which there is a straight, unpaved road that leads directly toward the basilica, with new apartments under construction to the left, and nothing else of visual interest nearby, and you'll have some idea of the rigid control of mise-en-scène that is typical of the film.

Actually, that shot encapsulates the other signature elements of Antonioni's style: a 55-second take is an eternity in film time, but this isn't a Welles-style showpiece; Antonioni just lets takes run for much longer than most directors. Also in that shot is his biggest narrative innovation: the character of Anna—of which more later. For now, the important thing is that she and her friend Claudia are about to embark on a yacht trip. Claudia, played by Monica Vitti, is at least a little more cheerful than Anna:

They're to be accompanied on the trip by Anna's boyfriend, a vainglorious architect named Sandro. He's the kind of guy who, when Anna turns to look at him, responds by saying "Should I give you my profile?"

Sandro inspires nothing but contempt and boredom in Anna; his great gift is that he's clueless enough not to notice. As one might expect from people with that level of world-class selfishness, they celebrate their reunion by having sex while Anna waits for them outside with the car.

They're perfect for each other. As Antonioni cuts back and forth between Sandro and Anna upstairs and Claudia below—left to her own devices, Claudia wanders through an art gallery, and we get the sense that she isn't quite as far gone as her friends.

The boat trip is basically as masturbatory as Anna's relationship with Sandro: shallow people with too much money attempting to divert themselves. In a sense, Sandro is the happiest of the lot, simply because he's too stupid to take anything seriously. Anna tells him that she wants to end things and all he can do is laugh it off.

Shortly after their conversation, Anna disappears entirely, and for a moment, we feel like we might be in a different kind of film, a mystery. There's no sign of her, and the only clue is the sound of what might have been a boat shortly before the lady vanishes.

Her friends perform a perfunctory search of the island, but you can tell their hearts aren't really in it. In a film that introduced the world to Antonioni's visual vocabulary, this is one of the shots were you can see how easily his style could slide into self-parody:

Only Claudia seems to really care what’s become of her friend. We’ve seen this movie before: the lost girl, the sparring aristocrats, the mysterious indifference. Claudia will eventually overcome the bureaucratic inertia of the Italian police department, discover that Anna’s friends know more than they are telling, and, in the end will discover the truth, standing as a woman alone against insurmountable odds. Right?

Well, not exactly. Claudia does take a solo trip to each of the nearby islands to see if there's any sign of Anna, and as in any film of this sort, there are tantalizing clues: the police investigation finds some smugglers who were in the area who seem to know more than they are telling.

But we don't accompany her on her tour of the islands, and the entire search turns out to be a false lead. Claudia cares less and less about finding her, and Sandro never really cares at all: within 24 hours he's coming on to Claudia.

Creepy. Claudia, for her part, pretty quickly gets over her reservations about sleeping with her vanished friend's boyfriend.

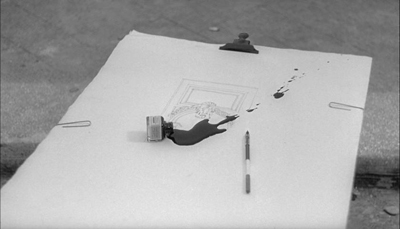

There is a moment when Claudia believes Sandro has found Anna, and has to confront her feelings about this (fear and shame), but that's the last we hear of her. The narrative winds down as the various characters lose interest in Anna's fate. Like Waiting for Godot, L'Avventura is mostly about passing the time. Sandro, an artist manqué, once wanted to be an architect, but now does cost analyses and consoles himself by knocking bottles of ink over on younger artist's sketches.

This is where the film starts to show its age: imagine making a film about the idle rich today, and making the idlest, most vapid character be an architect. Even the closest thing the film has to Paris Hilton is nominally some sort of writer. Antonioni couldn't have known it at the time, but the celebrity-industrial-complex was just getting ready to spit out things that were way uglier than the apartment buildings encroaching on Rome.

In fact, as awful as he's supposed to be, I like Sandro: I know that Claudia is the emotional center of the film, but Sandro's pettiness and insecurity is carefully observed and seems human. Films like L'Avventura are always just a single drawn-out philosophical conversation away from drifting away into the abstract, and Claudia serves as too much of an audience surrogate to really ground the film. This is not to say that she doesn't surprise from time to time, as when she makes faces at herself in the mirror:

For the most part, however, Claudia's role in the film is to be fluid and malleable; even her face-making revolves around trying on different identities. She toys with becoming Anna, borrowing her shirt, her fiancé, and even her hair.

Lynch must have seen this at a formative age. The difference between 1960 and 2001 is that in 1960, Antonioni still believes that there was an age of authenticity within recent memory. It produced the classical architecture that Sandro is always photographed in front of, and the ruins that appear in L'Avventura's final images.

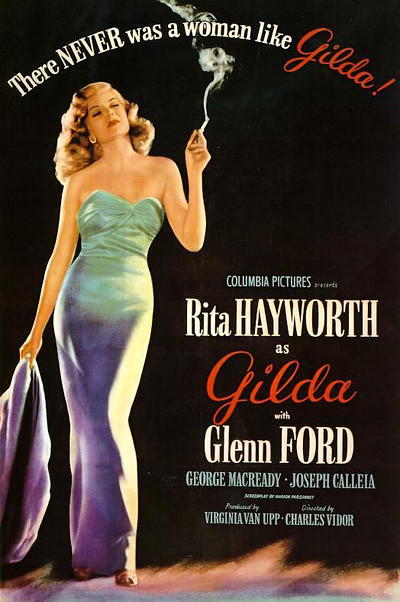

By the time Lynch makes Mulholland Dr., the only relic from the golden age is the image of one Margarita Carmen Cansino, post-electrolysis, post-dye-job, post-retouching. The tagline gives the game away:

No, there never was. I personally don't believe in golden ages. Some disastrous things may have happened to our culture in the twentieth century, but I think that the last generation with any claim to authenticity were primates. This isn't a new argument, either: Antonioni isn't saying anything in L'Avventura that you won't find in Ecclesiastes. So what matters is execution. L'Avventura is not an entertaining film (how could it be?), but its photography is a frame-by-frame refutation of any argument Antonioni could make about the death of culture. Maybe all he saw to do was catalog wreckage. But what wreckage, and what a catalog.

Randoms

- There's a wonderful DVD extra of Jack Nicholson reading an essay about how little regard Antonioni had for actors. Like, for example, Jack Nicholson, star of Antonioni's The Passenger. This is followed by a reminiscence in which Nicholson talks about how he didn't get the impression that Antonioni had very little regard for Jack Nicholson, star of The Passenger.