Some films enter the canon the minute their last frame clears the projector at a critics' screening. Other films need time and context before their greatness becomes apparent. Gimme Shelter, David Maysles, Albert Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin's magnificent film about the Rolling Stones' 1969 tour of the States, is a sterling example of the latter group. But not for the usual reasons.

In most scenarios where a film slowly becomes a classic, public taste has to catch up with the filmmakers—The King Of Comedy, for example, benefits greatly from more mainstream comedies of humiliation like "The Office." Gimme Shelter is something different, and as far as I know, unique: it needed time so that people could forget all about it. The Maysles originally planned something more like a traditional concert film, and the footage they shot at the Stones' Madison Square Garden concerts in November of 1969 pretty clearly fits that description. But the camera crews followed the band west on tour, which meant they were shooting at the Altamont Free Concert. And that's where the film's uncredited star made his appearance:

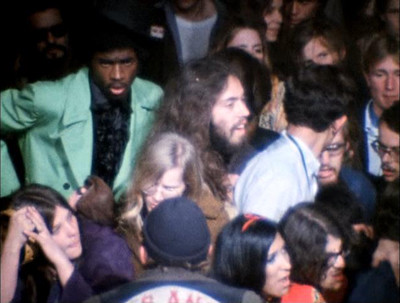

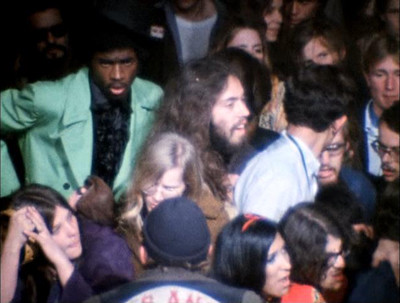

The man in the green suit is Meredith Hunter, eighteen years old. Not long after this picture was taken, he pulled a gun and was promptly stabbed to death by Alan Passaro, one of the Hell's Angels keeping people off the stage. The cameras captured the whole thing, from the stabbing to Hunter's girlfriend Patty Bredahoff weeping as his body is loaded into a helicopter. And the catastrophe at Altamont was enough of a scandal that everyone involved in its planning shared some of the blame in the national media, including the film crews.

It was pretty apparent that the Maysles couldn't just ignore Meredith Hunter's death and make a film like Woodstock or Monterey Pop. So they sort of made the best of it; with Charlotte Zwerin's help, they turned it into a film about Altamont, shooting the aftermath and reshaping the footage leading up to the concert so that Hunter's death becomes the inevitable climax to a slow-motion trainwreck that begins in Madison Square Garden. Regardless of whether or not they blamed the filmmakers for the concert's poor planning, critics found this in poor taste: Vincent Canby's review (original headline: "Making Murder Pay") charged the filmmakers of "epic opportunism," and Pauline Kael all but accused them of staging Hunter's death for the good of the movie. It must be said that their reactions were understandable: any film that is restructured at the eleventh hour to feature a real live death at its climax is going to carry a whiff of snuff about it. If someone gets killed at Lilith Fair this summer and Sarah McLachlan releases a film about it, I might go so far as to accuse her of exploiting a tragedy. But in the forty-odd years since Hunter's stabbing, Gimme Shelter stopped being "that failed concert film with a murder" and became "that film about Altamont." The question of who profits from Gimme Shelter seems much less interesting than the film itself.

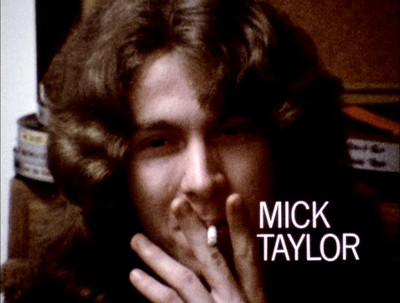

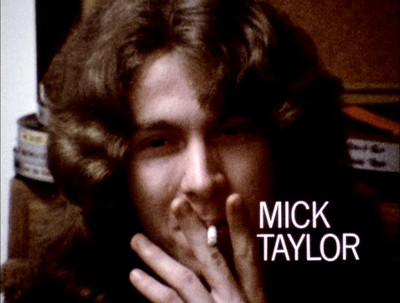

It's also undeniable that historical context has been kind to Gimme Shelter: something that couldn't have been knowable at the time. Forget, for now, about the "death of the sixties" if that kind of thing makes you feel like you've been cornered at a party by someone your parent's age who isn't aging gracefully. Let's just talk about the Rolling Stones. In 1968, they released "Beggar's Banquet." "Let It Bleed" hit store shelves on December 5, 1969, the day before Altamont. On deck: "Sticky Fingers" in 1971 and "Exile on Main St." in 1972. So within the five years around the film's release, four of the greatest records of all time. After that, the long, slow descent into self-parody: but no one could have known, in 1970, that Gimme Shelter captured the band at the absolute apex of their power as musicians and entertainers. The 1969 tour was the debut of the band's best lineup, thanks to the contributions of this man:

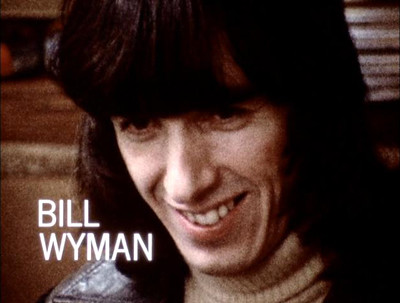

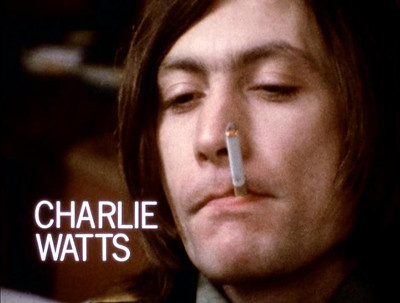

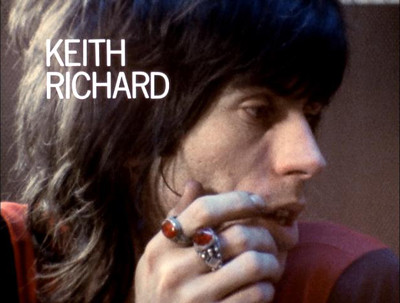

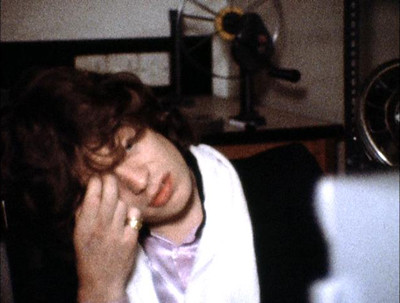

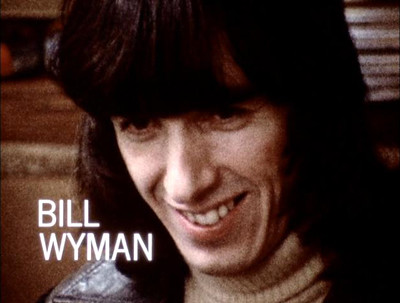

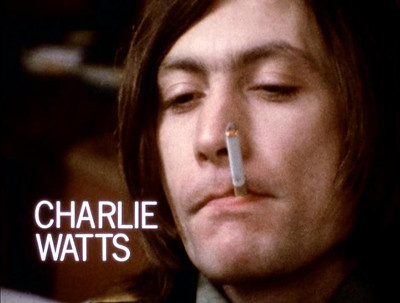

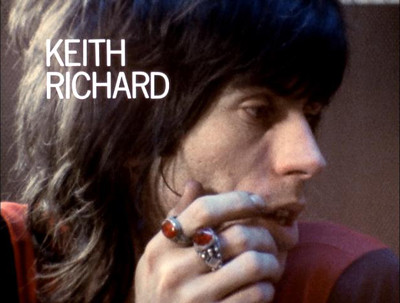

Taylor left the band in 1974; it's not a coincidence that they did their best work while he was playing guitar for them. You know the rest of the group, although I'd wager you haven't seen them looking this young in a while:

And of course, Mr. "Richard" and Sir Michael Jagger.

It's not just that this is the middle of the band's greatest period: it's that the Stones are still around, and have spent the last 30 years or so systematically sucking every last dime from their past glories. Watching Gimme Shelter, you almost wish someone at the mastering sessions for Exile on Main St. had slipped them a hot shot and a copy of Housman. But in 1970, no one could have predicted Zombie Keith Richards or Charming Old Pensioner Watts, and no audience or critic could have known how affecting it would be to see the band at their prime again.

And all right, let's get into the death of the sixties stuff. To me, if there was a signature event that brought on all the horrors of the 1970s, it was in 1972 with Nixon's victory over McGovern. But a lot of people would disagree with me on that: specifically the people who wrote the booklet essays for Criterion. For them, Altamont was the moment they were finally clobbered over the head with the fact that peace, love, and understanding wasn't going to be enough to save the world: this was a historical moment that resonated for years to come. Whether or not you agree with them, Gimme Shelter meticulously documents a lot of really naïve people running headfirst into atavistic tribalism and violence.1 And no matter where exactly in your timeline you jab the pushpin, that's how the sixties died.

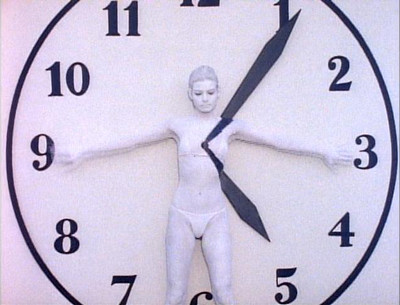

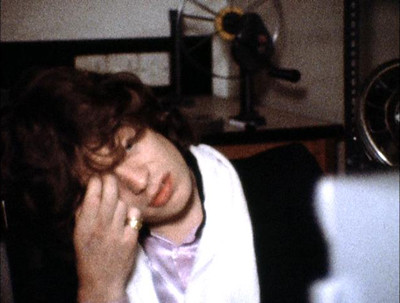

That's the context, but what about the movie? The fact is, whether or not it was in poor taste, Zwerin and the Maysles brothers did an amazing job of building a film around the Altamont catastrophe. Those stills of the band are all after Altamont, after the filmmakers knew they had footage of Hunter's stabbing, from a session where they invited the filmmakers to view rough sequences from the film, and caught them on camera reacting to themselves. And that's from the beginning of the movie: the first time we see the film's title, it's on an editing rig.

Just as in the editing sequence in Man With A Movie Camera (and oddly for what's ostensibly cinéma vérité), we're forcibly made aware that we're watching a manipulated reality, in which events happen out of sequence, circling Hunter's death like blood down a drain. This is brilliant (and essential) structurally, but it's also crucial for tone and theme. One of the film's great questions is the extent to which the Stones' manufactured stage personae contributed to the disaster at Altamont. By having the Stones watch themselves, the filmmakers create one of the most succinct critiques of celebrity on film. We see Mick Jagger clowning around at a press conference at the beginning of the tour:

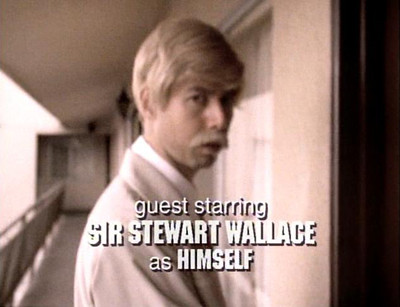

When asked by a female reporter if he and the band are "more satisfied" now than they were in the past, he asks if she means sexually, financially, or philosophically and then replies that they are "Financially dissatisfied, sexually satisfied, philosophically trying." It's a bullshit answer to a bullshit question, and the reporters eat it up. Months later, Jagger watches his response, hangs his head, and pronounces it "Rubbish."

It's not clear whether he's critiquing his answer or his performance, although in either case he's right. It seems clear that he's drawing a line between Michael Jagger and "Mick Jagger," until you remember that he's just taken a drubbing in the press over Altamont and knows he's on camera. It's a question that comes back again and again: cinéma vérité promises authenticity, but do these guys ever stop performing?

Jagger, at least, seems to be able to turn it on and off like a faucet. We see the band walk into a Holiday Inn: Keith looks a little crazy, but Mick looks like the London School of Economics student he once was:

In the very next shot, the band is leaving the hotel. The rest of the band looks the same, but now they're accompanied by Mick Fucking Jagger, Rock Star.

So this is an act. But it isn't all an act, because these guys really were the greatest rock and roll band in the world, and Gimme Shelter makes sure you know it. Before the first mention of Meredith Hunter, the film gives us an absolute barnburner performance of "Jumpin' Jack Flash," and let me just say that if you have never seen Mick Jagger command a stage in his prime, you don't know anything about the Rolling Stones.2 He's too kinetic to be captured in a still; you're gonna have to watch the movie.

Of course, Mick's command of the stage was part of the problem. His entire stage presence was built around taunts and provocation (sample patter: "You wouldn't want my trousers to fall down, now, would you?") and the Stones' music is not what you would call peaceful. So they were exceptionally great at riling people up; not so great at calming them down. By the time we see them perform "Honkey Tonk Blues," later in the film, we know Altamont is on the way. Which makes it ominous to see Jagger deal with fans who rush the stage; he just gets out of their way, lets the bouncers carry them off, and keeps singing. Ignoring the chaos around him is not going to be a great long-term strategy.

At about the same time, the filmmakers give the audience a different model of stage presence: Ike and Tina Turner performing Otis Redding's "I've Been Loving You Too Long."

The Stones' show is built around promising release, then denying it; Ike and Tina end the song with what appears to be an onstage orgasm and a whole lot of inappropriate microphone fondling.

It's just as provocative, but it's not built around chaos, and the audience is mesmerised, not rioting. Jagger's sullen response, watching footage of the opening act blowing him out of the water? "It's nice to have a chick occasionally.

Not in complete control of his emotions there.

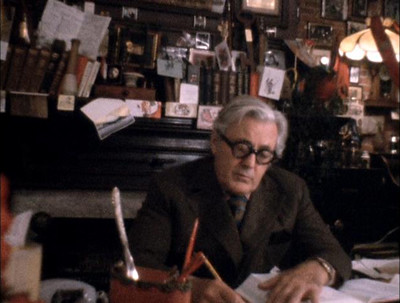

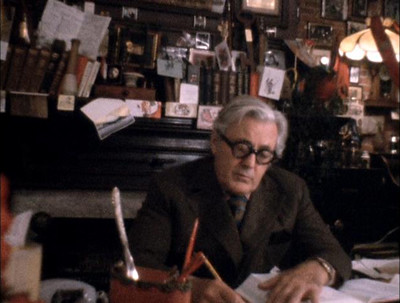

Adding to the sense of unease by this point is footage of Melvin Belli frantically negotiating with Dick Carter for the use of the Altamont Speedway. The original location for the concert had fallen apart, as had the backup location, and the Stones organization brought in the King of Torts, who you might recall from Brian Cox's portrayal of him in Zodiac.

Belli was by all accounts a brilliant lawyer, but his office is decorated like an Applebee's managed by Miss Havisham, and doesn't exactly give the impression of a man for whom organization came easily.

He's pretty cavalier about the whole thing: they have hundreds of thousands of would-be-concertgoers descending on San Francisco for a concert, no toilets, no parking, no doctors, nothing, but everyone seems to think everything will just sort of work out somehow. Someone in the room says it's like "lemmings to the sea," and they're not far off.

By the time the concert starts, disaster seems inevitable. This:

Is not a man who is culturally prepared to deal with this:

That's one of the Hell's Angels. Depending who you ask, they were either hired or decided on their own to provide "security" with weighted pool cues. They weren't exactly what you'd call Stones fans, judging by the look one of them gives Mick Jagger:

Over the course of the afternoon, they got drunk and out of control: they punched out Marty Balin during the Jefferson Airplane's set, they beat the crap out of any number of concertgoers, and when Meredith Hunter pulled a gun, they stabbed him to death.

Despite their rough edges, the Stones were about as well prepared for real violence as that guy with the magic wand. Arriving at the concert, Mick gets immediately punched in the face; when fights break out, all Jagger can muster up is, "If we are all one, let's show we're all one." That sentiment is exactly as effective as you'd imagine. Sonny Barger and company weren't interested in being "one" with a bunch of hippies. Especially not hippies who were—as Sonny pointed out in a radio interview after the concert—messing with their bikes: they "got got." And unfortunately for the Stones, being able to work a crowd into a frenzy does not mean you can get that same crowd to chill the fuck out. It's a different skill set.

So that was Altamont: a slow-moving catastrophe where none of the people who could have stopped things were paying enough attention. But the cameras were rolling. Albert Maysles, David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin couldn't see what they had until they got into the editing room and shaped it into something coherent. Most critics couldn't see what they'd created until decades later, when the film's origin had faded and the Rolling Stones had gone on to Super Bowls and president's birthday parties. What are we left with? Gimme Shelter is an undeniably great concert film, and if not for Altamont, that's exactly what it would have been. It's also a process documentary about a very badly planned concert, but it's more than that, too. I hesitate to pronounce it the obituary for sixties, although at times it certainly wants to be. For me, the film's most interesting moments have to do with Jagger's control of his public persona: the moments when you see his façade slip and immediately get put back in place. Watch Gimme Shelter carefully, and you will see the Rolling Stones become the greatest rock and roll band in the world through sheer force of will. Even if people have to die.

Randoms

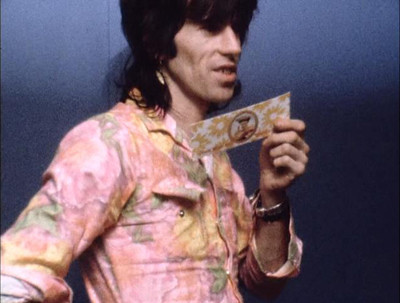

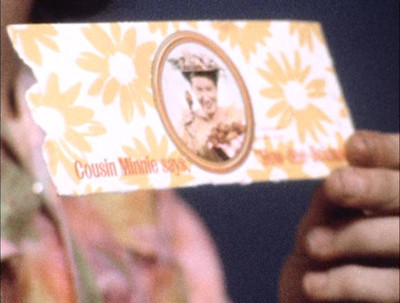

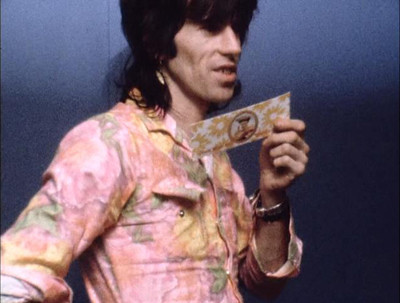

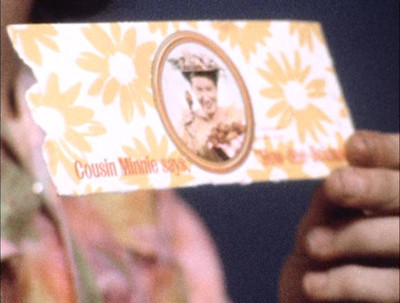

- Gimme Shelter has one of my favorite Keith Richards moments, a shot of him explaining that he's taking a box top from Minnie Pearl's Fried Chicken home as a souvenir.

Cousin Minnie says, "How dee-licious!"

Minnie Pearl's Fried Chicken is no longer with us: it flamed out in a political scandal as big as Altamont. If you ask me, that's when the sixties really died.

- If you want to see the Rolling Stones a little later in their career, track down Robert Frank's unreleased, unreleasable documentary of their 1972 tour, Cocksucker Blues. It's pornographic, has a lot of dull conversations with junkies, and the performances aren't as great, but it's worth it for the scene where Keith Richards attempts to order a bowl of fruit from room service. You can find it on YouTube.

- The DVD and Blu-Ray feature galleries of Altamont photos by Bill Owens and Beth Sunflower. I like this one, by Bill Owens:

It looks like something Robert Capa might have shot.

- Please feel free to argue in the comment section that the Rolling Stones were not the greatest rock and roll band in the world. You are wrong about this. Thank you.

- Update: As the very well-informed commenter R-Man points out, I neglected to mention that one of the cameramen at Altamont was a young George Lucas.(And apparently

Spielberg Scorsese (thanks, anonymous commenter—don't know what I was thinking) was one of the cameramen at Woodstock).

1Which is pretty much what happened to the McGovern campaign, come to think of it.

2I didn't: Gimme Shelter was how I got into the Stones, after Oldies Radio and the Steel Wheels tour poisoned them for me.