The Third Man, 1949, directed by Carol Reed, written by Graham Greene.

The first time we see Joseph Cotten as Holly Martins, the hapless protagonist of The Third Man, he's craning his head out of a moving train as it pulls into the station. He does a lot of that throughout the movie. Martins has the perpetual cocked head of a dog trying hopelessly to puzzle something out. And as the third shot of him suggests, his cluelessness isn't going to bring him any good luck:

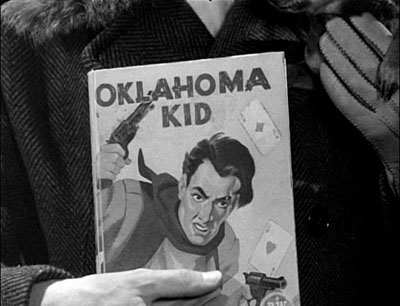

That's Holly in a single shot: too caught up in whatever's going on inside his head to notice he's walking under a ladder. Now there's a fine tradition of films about preoccupied bumblers—mostly comedies—and you could imagine that shot in any number of movies. But this isn't The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, and there's nothing charming about Holly Martin's obliviousness. As Jim Shepard points out in "Zane Grey and the Borgias: The Third Man and the 2004 Republican Ticket" (the definitive essay about The Third Man; buy yourself a copy here), the key thing about Holly is that he doesn't realize that "being in over his head might be dangerous for other people." He has the peculiar American combination of determination, self-righteousness, and ignorance that creates disasters like our current adventure in the Middle East. How ingrained is his belief in saving the day through nothing but sheer pluck and true grit? Well, he writes cowboy novels with titles like The Lone Rider of Santa Fe, and covers like this one:

There may be situations where Westerns are useful moral guides. But the Viennese black market immediately after World War II was not one of them, and unfortunately, that's where Holly finds himself.

The movie opens with a brief tour of Vienna's moral squalor during the Four Powers occupation, 1945–1955. At the time, Vienna was divided into four main zones, governed by the French, Americans, Russians, and British. In the center of the city was the inter-allied zone, rather ineffectually governed and policed by representatives of all four governments, who had no languages in common but pidgin German:

You can see a map of what the city looked like here; Europe's very own Texarkana. Enter Holly Martins, who's come all the way from America to get a job working for his old school friend Harry Lime. But Holly's barely off the train before he discovers that Harry is dead, the British are claiming he was a racketeer, and the one thing everyone (British, Russian, Austrian, even a Bulgarian) agrees on is that Holly should go home. Which is, of course, the one thing you don't tell an American to do. Especially if you're a sardonic, world-weary Brit like Major Calloway, played brilliantly by Trevor Howard.

So after getting drunk on the British delegation's dime (or pound note, I guess) and trying to punch Major Calloway in the face, Holly has the single worst idea of his life: he's going to investigate and clear Harry's good name.

This despite, as Shepard points out, the fact that "He doesn't know the city at all, and doesn't speak German. Or Russian. Or French." He may as well put a sign on his door reading "Gareth Keenan Investigates!" Holly's ill-fated venture begins with a meeting with one of Harry's oldest, dearest friends in Vienna, Baron Kurtz. He seems as friendly and sincere as Holly seems competent and restrained:

And things pretty much go downhill from there. The archetypical Holly Martins scene is his first meeting with Lime's girlfriend, Anna. She's an actress; he goes to one of her performances, and sits stone-faced and uncomprehending at the German dialogue while the audience around him roars with laughter.

After the show, he tells Anna, "I enjoyed the play very much. You were awfully good in it." She cuts him off: "Do you understand German?" Not. Fooling. Anyone. He does find one thing that the police didn't know: the reports of Harry's death turn out to have been exaggerated.

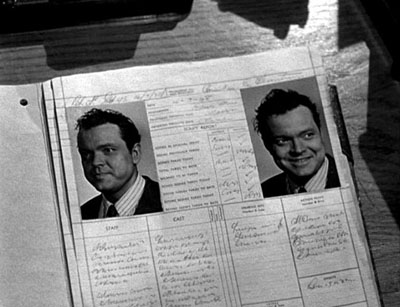

That's Orson Welles as Harry Lime, making his unexpected reappearance in one of the most famous shots in film history. But for my money, the shot that should have entered the canon is this insert shot of Calloway's file on Lime:

As mug shots go, it could have gone worse. And as photos of Orson Welles go, it did go worse. Anyway: Welles's performance is excellent, but it didn't have to be much. He doesn't appear until an hour into the film, and the first hour is spent with every character talking about him. There's an interview with Peter Bogdanovich on the DVD in which he says Welles compared playing Harry Lime to playing a character named Mr. Wu back in his theater days. (Bogdanovich doesn't identify it further, but probably Welles was referring to the play this was based on). In Mr. Wu, any time in the first act that a character says anything at all, another character says something like, "But what will Mr. Wu think about that?" or "Well, we'll have to wait and see what Mr. Wu has to say." And at the very end of the act, Mr. Wu is seen arriving in the distance, in silhouette. He has no lines. But according to Welles, at the intermission his performance as Mr. Wu was all anyone could talk about. The Third Man works more or less the same way; after the buildup Lime gets, all Welles has to do is show up.

Needless to say, the more Holly blunders around Vienna, the worse he makes things for everyone, from Major Callaway up to Harry himself. But nobody gets off worse than Anna, because Holly decides he wants to save her. She's played by the great Alida Valli, and brings shades to the part that I doubt were apparent in the script. Her complete lack of patience with Holly is one of the film's great pleasures.

When Holly tells her he's fallen in love with her (in a typically self-pitying fashion), she replies, "If you'd rung me up and asked me if you were fair or dark or had a mustache, I wouldn't have known." Holly being Holly, however, he's still dumb enough to wait for her after Harry's second funeral (trying to salvage the happy ending, as Shepard put it). Anna has the only rational response: she walks right past him without even acknowledging he's there.

Randoms:

- There are a lot of great performances in this film. Trevor Howard's Major Calloway is nearly perfect. He gets most of the best lines (e.g., "I don't want another murder in this case and you were born to be murdered.") And then there's this scene:

- Holly is on his way out of town, and he won't help Calloway catch Lime; Calloway says he has to make a stop on his way to the airport. The "stop" is to the children's hospital where some of Harry Lime's victims are living (Lime has been diluting and reselling penicillin). We never see what's in those cradles, but watch Calloway's face as he explains, "It had meningitis. They gave it some of Lime's penicillin." That it.

- The final chase scenes through the Viennese sewers are justly famous for their cinematography and staging. Two examples:

- Two things I didn't know about this section of the movie: first, you know those weird cops in jumpsuits that show up out of nowhere? Vienna had an actual squad of police whose beat was the sewer system, and those are their uniforms. The DVD includes an old Pathé newsreel with footage of them in action. Here they are:

- The other thing I didn't know is that Orson Welles's shots in this section are all on a soundstage, because he refused to shoot in the actual sewers after the first day.

- Trivia everyone knows: Orson Welles wrote the monologue about Italy under the Borgias himself. So he may be the only person on the planet who has written something better than Graham Greene did.

- Trivia not everyone knows: Carol Reed worked nearly 24 hours a day on The Third Man all throughout the production (three units were shooting simultaneously). His secret? He was a Benzedrine achiever.

- More trivia everyone knows: the entire score of The Third Man was performed on the zither by Anton Karas, who Carol Reed heard playing in a restaurant and insisted on hiring over the objections of everyone at the studio. If you've ever wanted footage of Karas playing, this is the DVD for you:

- What I didn't know was how a zither actually works: it's the kind of instrument you hear about more than you actually see. It's sort of a mix between a harp and a guitar:

- If you think about the Harry Lime theme from the film (and if you don't know it, see the movie—it will be stuck in your head for weeks), you can see how it works; the right hand plucks the bass line on the non-fretted strings and simultaneously plucks the treble strings with the thumb pick; the left hand frets the upper strings. That's why the score has relatively simple bass lines, particularly when the melody gets rolling.

- Last thing, and something I didn't notice until this viewing (and only then because Roger Ebert mentioned it). It's part of the subplot involving Holly Martins delivering an ill-advised address to a cultural reeducation society. The organizers mistakenly believe he is a significant novelist; it's a humorous version of the "Holly out of his league" disasters that move the main plot along. But what I didn't notice was that the head of the reeducation group almost always is accompanied by his mistress, who he maneuvers out of the way before talking to anyone:

- Once you see her, you'll notice that she's almost always with him; his performance is a case study in guiding a companion to the sidelines of a conversation; Crabbin does it reflexively. In the shot above, he's about to pull her between himself and Sergeant Paine and off to the side, without breaking eye contact or otherwise acknowledging her. Crabbin's first line is to her: "I can't very well introduce you to everybody." It's a nice counterpoint to the way Anna Schmidt is manipulated by the rest of the characters. So: old British men looking to avoid social scandal, take note!