Rushmore, 1998, directed by Wes Anderson, written by Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson.

Wes Anderson has the dubious honor of being perhaps the most polarizing director of his (and my) generation. This is not entirely his fault. Since Rushmore, he's served as a proxy target in cultural wars that were only marginally related to his work. To be fair, he brought the first of these on himself, by writing an article for the New York Times about screening Rushmore for Pauline Kael. Apparently Kael (being treated for Parkinson's at the time) was not too coherent. Apparently Anderson's article made this clearer than was probably polite. It seems that insulting someone who mentored an entire generation of film critics is not the best thing to do if you want your film reviewed kindly; David Edelstein's piece in Slate is a decent example of the resulting fallout. And Anderson also serves as a convenient target for people who don't like people who like movies by Wes Anderson. And they have a point. My roommate saw Rushmore for the first time sitting next to an insufferable prick who kept applauding at every other line. But neither of these experiences—repugnant as they may be—have that much to do with Anderson's films themselves.

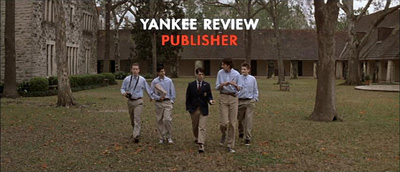

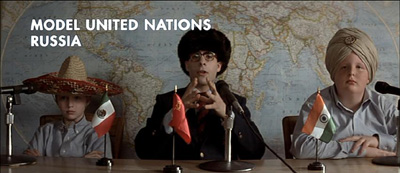

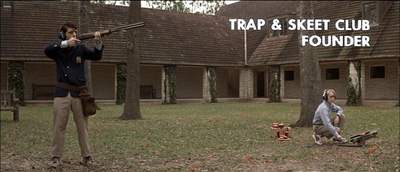

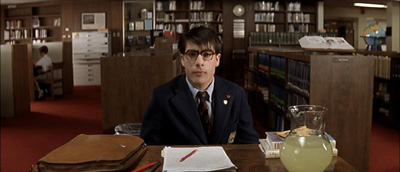

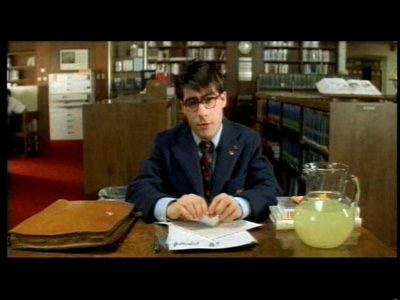

And this isn't really the place to write an account of all of his work. Anderson has a deal of some sort with Criterion; everything but Bottle Rocket is available in a Criterion edition. So we'll get to the rest of it sooner or later. For now: Rushmore, Anderson's first foray into J.D. Salinger territory. Jason Schwartzman plays Max Fischer, Rushmore Academy's most enthusiastic and least focused student. One of the film's highlights is a brief montage of Max's extracurricular activities. These start with the prosaic:

And slowly devolve toward the bizarre:

Before ending up with the wholly fantastical:

The whole thing is over "Makin' Time," by The Creation. And there you have Wes Anderson's style in a nutshell: a great British invasion soundtrack, anamorphic wide-angle lenses to the point of absurdity (there's hardly a straight horizontal line in the film—check out the front row of language booths in the French Club shot), willfully obscure allusions, and FUTURA BOLD. Lots of FUTURA BOLD. Your response to that series of stills is a pretty good litmus test for how you'll feel about the rest of the movie. If you find them pretentious and dull, steer clear. If it seems a little twee but the visual style is intriguing, stay with it; it gets better from here. If the idea of making Model UN members wear country-appropriate hats, or firing off a shotgun in a school courtyard, or keeping bees at school struck you as amusing, you're going to love Rushmore. And if the shot of the Yankee Racers reminded you how much you love Jacques Henri Lartigue...

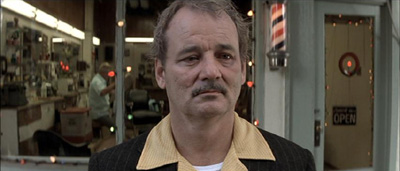

...then odds are you're Wes Anderson. Welcome! The movie traces a strange friendship between Max Fischer and depressed industrialist Herman Blume:

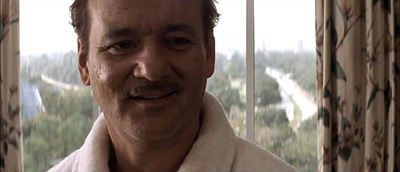

Blume is Bill Murray's best version of a character he's been playing again and again for the last eight or nine years (for that matter, Max is the best version of Jason Schwartzman's screen persona). You thought Murray was unhappy in Lost In Translation? Compared to Rushmore, he was ecstatic:

Sofia Coppola was right to have Murray's wife and kids only exist over the phone in Lost in Translation; her movie was about loneliness, not misery. But the single best decision Wes Anderson may have ever made was casting Ronnie and Keith McCawley as Ronnie and Donnie Blume, Herman's terrible sons. Here, they're locking him out of his car:

And one of them is responsible for his black eye in the earlier still. "Never in my wildest imagination did I dream I would have sons like these," Herman tells Max, quite credibly.

Max and Herman don't have much in common, but they fascinate each other. Max sees Blume as an emblem of triumph in the class wars. Max's secret shame is that he attends Rushmore on a scholarship. Like Charlie Brown, his father is a barber. Unlike Charlie Brown, he tells everyone that his father is a neurosurgeon. For his part, Herman sees Max as someone who hasn't yet lost his enthusiasm for the world around him (even if he's mostly enthusiastic about a fantasy world he's creating). Unfortunately, they both become enthusiastic about the same woman, a second grade teacher named Rosemary Cross.

Olivia Williams isn't given that much to do in this role; she mostly has to react to Max and Herman as they get pushed over their respective edges. Which she does admirably well. Unfortunately, the best way to deal with someone who is trying to get your attention in inappropriate ways is to ignore them, so Williams gets less screen time than she (and I) might have liked.

Rushmore plays out as most love triangles do, at least when one of the men is a teenager and the other is in the middle of a midlife crisis. Which is to say: unpredictably. I defy even confirmed Wes Anderson haters not to enjoy Max and Herman's revenge montage, which begins with Max letting live bees into Herman's hotel room and ends with prison. At three minutes long, it's a model of economy. Usually, montages elide scenes that would be dull if seen in full (imagine watching one of Rocky's full training sessions). In this case, however, Anderson takes scenes that would be much longer in any normal film and compresses the hell out of them. And it's not just plot that happens here; we learn a lot about Blume from his that sonovabitch smile when he realizes Max is responsible for his bee stings:

Seeing Murray's face slide from the above expression into one that says, roughly, "Max Fischer is gonna pay," is one of the film's great moments. Particularly when it's set to the music of The Who, it seems, revenge can be a terrific amount of fun.

When you get past the extraneous bullshit surrounding Anderson's films, the crux of disagreements about him reminds me of disagreements over David Foster Wallace (or Dave Eggers, or Thomas Pynchon, or even Vladimir Nabokov). It comes down to this: Are Anderson's stylistic tricks and distracting plot elements smoke and mirrors, or do they bring something unique to the stories he's telling?1 In the case of Rushmore, I think the answer has to be the latter.

The heart of the movie, for me, is not how charming or quirky Max is (which is basically what Edelstein seems to believe). If you're paying attention, it's clear that Max's manias are fueled by unhappiness as much as narcissism. When he tells Ms. Cross that Harvard is his safety school (if he doesn't get into Oxford or the Sorbonne), he's not just trying to impress her; that's really the standard he holds himself to. And he holds himself to that standard because his mother, who encouraged him to write plays and got him into Rushmore Academy, has died of cancer. In that context, you can read Anderson's visual style in the first act (which is the most boldly colored) as something like what Max is up to: a calculated campaign of distraction from genuine pain. The colors get washed out as soon as Max gets expelled from Rushmore Academy, and they don't return to their original boldness until Herman's haircut, at the beginning of the final act. Even the filmic references get duller: you couldn't put an homage to Frederick Wiseman in the sections at Rushmore Academy, but it fits right in at Grover Cleveland High School. When Max can't keep up his tap dance over the abyss, neither can the film.

So to me, Rushmore is a movie where style and substance are pretty unified. And you shouldn't scoff at Anderson's achievement here; unified style and substance are a lot easier to do with a pessimistic film (e.g., Children of Men) than in one where the tone is something like "bittersweet optimism." Which is not to say it's a universally appealing film throughout; you either think the idea of a theatrical version of Serpico is hilarious or you don't.

I do. And I think the movie has one of the most satisfying endings in film history. Max puts on a play at his new school about the Vietnam war and invites everyone from the rest of the film. At the afterparty, they all get along like gangbusters. And everyone is in these final scenes; there's no villain who must be excluded as a condition of the heroes' happiness. The first play of Max's we see, it's apparent that he's interested in the acclaim it can bring him. The last play, he's discovered the more rewarding purpose art can serve. He's creating an environment in which all injuries can be healed, all sorrows forgotten. And of course, that's not just Max's goal, but Anderson's. It takes heroic efforts (and in Max's case, flamethrowers, dynamite, and a wildly inaccurate understanding of the Vietnam War). And it never lasts long. But it's what art can do, at its very best. In the final shot, as if in recognition of how fleeting happiness and reconciliation like this always are, Anderson uses a variable-speed camera to stretch the moment out as long as possible. The times I've felt that way, that's how I remember it.

Randoms:

- Even the best (and funniest) critique of Anderson's films so far, Tyler Burr's review of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, has some reflexive hatred of hipsters (Burr describes Anderson as the kind of person who "wears interesting socks.") Not that there's anything intrinsically wrong with hating hipsters.

- Much has been made of Anderson's debt to Salinger. I think Rushmore owes more to Hal Ashby, frankly. There's clearly a straight line between Harold and Max's narcissism, just like there's a straight line between Max's slow-motion semi-sneer after his version of Serpico:

- And Harold's expression after successfully faking self-immolation.

- I'm a big fan of 2.35:1 in general; and I'd like to go on record now as saying that 2.35:1 anamorphic, attached to a wide-angle lens (in the case of Rushmore, a 40mm lens for everything) looks fantastic. I don't know if it's the lens or the film format, but the images look sharper and denser, even on DVD, than in other films I've seen. However, if you're shooting your film in this format, please be sure that everyone in post and publicity knows how you want it treated. The DVD features an interesting joint appearance on The Charlie Rose Show by Anderson and Bill Murray—with a horribly distracting bad transfer of film clips. Here's a shot of Jason Schwartzman in the film itself:

- And here's the way it showed up on Charlie Rose (uncropped, so you're seeing the full video image):

- Granted, the blurriness is inevitable when you're looking at something that was transferred from a tape of a television program, which featured a broadcast of a tape of a film, which was undoubtedly transferred in a hurry to whatever format the show's producers required. But I wonder if Rose insisted that clips be in no wider aspect ratio than 1.85:1? This still is at about 1.77:1, and to get there, they've cropped the sides of the image. That's relatively normal. But they've also incompletely expanded it horizontally. Schwartzman's shoulders are skinny enough in that blazer—from which the pads had been removed—in the original still. Here, he looks like a beanpole. For all of you who couldn't give a damn about film transfers under any circumstances, I offer my sincere apologies.

- Anderson gets a lot of credit from me for discovering Brian Cox's comedic talents. Or at least for bringing them to my attention. Anderson cast him as Dr. Guggenheim, the director of Rushmore Academy, on the strength of his performance as Hannibal Lecktor (yes, that's spelled right) in

Red DragonManhunter.2 Because when you're casting "principal," you think "serial killer," not "a prince! and a pal!"

- Apparently, the real life Bill Murray hated the real-life actors who played his sons just as much as Herman Blume hated their characters.

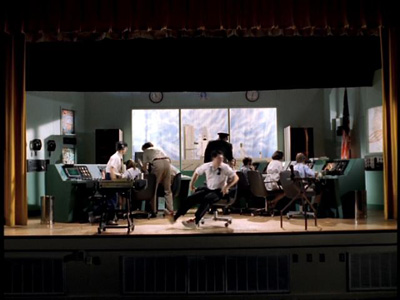

- Finally, I recommend buying or renting the Criterion version of Rushmore because it has one of the very best extra features of any DVD I know. For the 1999 MTV Movie Awards, Wes Anderson directed his own versions of Armageddon, The Truman Show, and Out of Sight, as performed for high school theater by the Rushmore Players, directed by Max Fischer. They're fantastic. And in the most obscure joke on the DVD, Anderson has Max Fischer slide across the stage on a chair during the NASA scenes from Armageddon:

- Why? Because Max Fischer is the director. And Michael Bay did the same slide in the same rolling chair, for just as little apparent reason, in his cameo in Armageddon.

- It's a two-percenter, but I love it.

1Actually, in the long term, the question you can have more interesting disagreements about is whether it matters; some filmmakers and writers seem to think divorcing style from substance is desirable (cf. Tarantino, Leyner). As you've probably figured out if you've been reading this blog, I am not one of them.

2Nothing's more embarrassing than being a pedantic asshole about the correct spelling of a character's name in a particular version of a film, and then getting the title wrong. And not just "wrong," but "confused with a Brett Ratner movie." I suppose the take-home lesson should be to try not to be a pedantic asshole. But we all know that's not going to happen.