Carnival of Souls, 1962, directed by Herk Harvey, written by John Clifford.

I write a lot about comedy as though it were the great neglected genre. And it's true; comedies don't get a lot of critical acclaim. But nobody gets less respect than horror movies. Except for B-horror movies from the sixties. And the only films that get less respect than B-horror movies are B-horror movies made in Lawrence, Kansas, by filmmakers who never worked on another feature. So what is Carnival of Souls doing in the Criterion Collection? I'd love to report that it's a brilliant film, a lost gem of incalculable worth. Well, it's not. But it's not quite a B-picture, either. The filmmakers got a lot wrong; the sound is laughably badly mixed, there are some terrible performances (and some passable ones), and a great deal of the movie, particularly toward the end, just isn't very frightening. But in the weeks after you see it, you will find yourself remembering some of the strangeness of the film, its odd tone, its uncanny images.

And even if you don't, you'll remember the movie because of its strange pedigree. Variety's review began, "Occasionally a feature film emerges from the midwest..." John Clifford and Herk Harvey were both employees of Centron Studios, one of the big three producers of educational and industrial movies (the other two were Coronet and Encyclopædia Britannica). And like any good social guidance film, it opens with young people making a terrible decision. In this case, they agree to drag race, which ends pretty much how you would expect.

If the movie had been directed by Sid Davis, that would have been the last shot. If it had been a Highway Safety Foundation production, that wouldn't have been the last shot, but audiences would have wished it was. In Centron movies, though, things always tended to be a little murkier. And speaking of murky, the car crash isn't as tragic as it looks, at least for one of the passengers.

That's Candace Hilligoss playing the sole survivor, Mary Henry. She remembers next to nothing about the wreck, but we see her haunting the bridge soon after, staring into the water. We don't see anything of her life in Kansas, where the movie begins, except for a brief scene of her practicing organ on the assembly floor of the Reuter's Organ Company:

She's not always shot from such a distance, but she is consistently apart from everyone else in the movie. Apparently on the theory that a change of scenery will do her good, she leaves town as soon as she can, to take a job as a church organist in Salt Lake City. Asked to "stop by and see us the next time you're in," she replies, "Thank you. But I'm never coming back." She's as good as her word.

On the drive west, her radio goes on the fritz: whatever channel she turns it to, all it picks up is organ music in minor keys. In the distance, she sees a hulking building across the salt flats:

And almost immediately she runs off the road to avoid hitting a gaunt apparition who looks suspiciously like the director wearing grease paint:

And there her troubles begin. For the rest of the movie, Hilligoss keeps seeing this guy, and finds herself strangely fascinated by the strange building she passed on the highway. That building is the movie's secret weapon, and I believe it is the reason it has survived so long. On his way back from a vacation in Los Angeles, Herk Harvey passed the same hulk of a building off the freeway, and was curious enough to pull off and check it out. What he found was the wreckage of a grand experiment in Mormon entertainment, created while the church was distancing itself from its first grand experiment in Mormon entertainment, "celestial marriage."

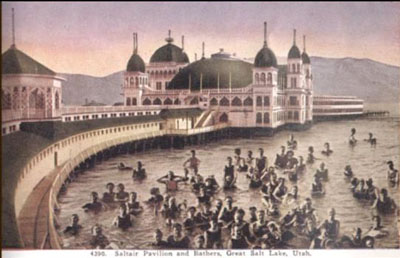

In 1893, the Church of Latter Day Saints built a resort on the edge of the Great Salt Lake to provide wholesome entertainment for young families called Saltair. It featured salt water bathing in the lake and a grand pavilion on piers over the water, and was remarkably successful:

Believe it or not, you're looking at one of the most famous tourist attractions of its time. In 1925 the whole thing burned to the ground and was rebuilt on a slightly less grand scale:

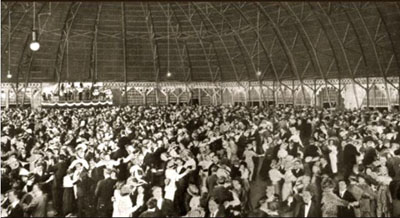

Notice that the large central tower is missing, as is the second level of the promenade. You can also see the park's roller coaster and the railway tracks leading in near the road. The centerpiece of Saltair's second incarnation was the enormous dance pavilion. I believe this photo is of the second dance pavilion, at its time one of the largest in the world:

In the late 30s, the salt lake receded away from the pavilion, leaving it on a great muddy plain, which proved to be somewhat less appealing to vacationers. Still, they limped along until 1958; so when Harvey shot there, it had been closed for about three years. Here's what he found:

That's the wreckage of the main pavilion. Here's its interior:

It would be hard to do a bad job shooting such an evocative location, and the scenes at Saltair are the best in the film. And I think there's something about using an actual abandoned resort that gives this section moments of creepiness that a more calculated film wouldn't have had. For instance, imagine how you would create a deserted carnival for a horror film (or play a few hours of Carnevil). Then ask yourself if you would have included anything as sad as a long-abandoned Barrel of Fun:

Or as uncanny as the bad advertising art on the wall here (the sign is for Salt Water BATHING, but the woman's face seems to be an advertisement for Inter Family BREEDING):

No set designer could come up with anything as weird, sad, creepy, and appropriate as Harvey and his crew found in the wreckage of Saltair. I admit it. I'm a sucker for abandoned places, and I would have been perfectly happy with two hours of footage of what was left of Saltair. The film offers other pleasures as well, however, most notably Sidney Berger's performance as Hilligoss's lecherous neighbor:

His character is a type of person you don't see too much of in film. He's fiercely anti-intellectual, but in kind of a charming way, starts his day off with whiskey in his coffee, and comes on to Mary Henry full speed ahead from the moment he sees her. In fact, his pursuit of Mary Henry is the focus of the middle third of the film, which is kind of strange because it isn't supernatural in the least. In the horror movies I'm used to seeing, by the end of the first act most subplots are subordinated to whatever the main horror of the film is, but this one doesn't intersect with Mary's other problems at all until the end of the second act. It's a strange choice, but actually, the scenes between Berger and Hilligoss are some of the best written and fastest moving in the movie.

The Criterion edition features two cuts of the movie; the original theatrical release (which features some cuts in the final third) and the original version. In both cuts, a lot more could have been sliced without being missed. There's a recurring scene where Mary Henry becomes invisible to those around her: it's very well done the first time. But the second time it drags on to the point of parody. One of the moments of sheer pulse-pounding terror, for instance, is that she is unable to hail a cab:

And she has even worse problems at the bus station. Needless to say, transportation problems aren't the stuff of nightmares. But despite all the goofiness towards the end, Carnival of Souls has some moments of inspiration that transcend its Z-movie roots. Even Herk Harvey in greasepaint has one moment of being truly horrifying, rising silently from the salt lake towards the camera.

Randoms:

- If that last shot of Harvey looks familiar, it should. Francis Ford Coppola stole the shot (and the creepy, lifeless way Harvey rises out of the water) for Apocalypse Now. Carnival of Souls may be more famous for the later, better films that stole from it than it is great in its own right. George A. Romero has admitted modeling his zombies in Night of the Living Dead on Harvey and the other ghosts in this film. And although there's no direct link, I can't help but think that the Overlook Hotel in The Shining has a little bit of Saltair about it; look again at the picture of dancers in the main ballroom in the place's heyday. Whether or not Stephen King was familiar with the movie, I have no doubt that Kubrick was, because there's a scare shot that's identical to one he used in The Shining. Mary is in her room with John Linden; he leans close behind her and kisses her neck:

- When she looks up at their reflection in the mirror, however, she finds Herk Harvey's character leering back at her.

- The idea is better executed in The Shining, but there's no mistaking its origins. It's a strange kind of cinematic glory, to be a well that many more gifted filmmakers have drawn from, but it's better than nothing.

- Harvey and cinematographer Maurice Prather had a great eye for mathematically precise compositions. You can see it in that great shot of Mary at the organ above, and in the following stills, all with very strong diagonal layouts. Notice how precisely the building's shadow defines the frame below:

- Of course, organs are naturally pretty mathematically precise:

- This last one is symmetric, not diagonal, but is probably my favorite shot in the film; it's from inside the dance pavilion looking out on the salt flats:

- Virtually the entire crew had a long career at Centron both before and after Carnival of Souls. The DVD includes a lengthy section of excerpts from Centron films. Here's a younger Herk Harvey in one of them, Star 34.

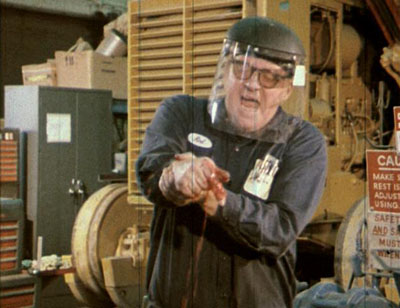

- Star 34 is about a couple from some unnamed large city who inherit a significant amount of money from a distant relative, provided they tour the state of Kansas and learn about its many attractions. Guess which snobbish-at-the-beginning-of-the-film couple fall in love with Kansas? But despite having a clip from Signals: Read 'Em Or Weep, the DVD unaccountably omits Shake Hands With Danger, Herk Harvey's closest thing to a Sid Davis movie, in which construction workers meet disaster after disaster by ignoring workplace safety. Here's a sample:

- What really makes the film, though, is its bizarre soundtrack, by a Johnny Cash sound-alike. Sample lyric:

- As easy as it is to snicker at educational and industrial films (and not just easy, but fun), it bears remembering that they were big business in their day. The best, and as far as I know only, source of information about them is Ken Smith's excellent Mental Hygiene: Classroom Films 1945–1970. I can't recommend this book enough. Other invaluable resources are Skip Eisheimer's Educational Archives series of DVDs (the source of the Shake Hands With Danger stills above) and the Prelinger Archives.

- I can't think of another film that was inspired by a single location the way Carnival of Souls was, but I can think of some locations that should have inspired films. My pick would be Heritage USA, the remains of Jim Bakker's criminal empire. Check out the "Take a Tour of Heritage" to get a feel for the place. You could do a lot of interesting things shooting in the Grand Tower. If anyone else has great location ideas, leave them in the comments.

Shake hands with danger

Meet a guy who oughta know

I used to laugh at safety,

Now they call me... Three-Finger Joe.