Brazil, 1985, directed by Terry Gilliam, written by Terry Gilliam, Charles McKeown, and Tom Stoppard.

In Brazil, Terry Gilliam asks the audience to imagine a world where the government wages a never-ending war with shadowy terrorists, a world where civil liberties are being destroyed in the name of security, a world where torture becomes official state policy in order to conduct more efficient interrogations of suspected terrorists. What's more, in Gilliam's fictional world, the central government is not just secretive but incompetent. Mistakes are made, leading to the imprisonment and torture of innocents. Most offensive of all, Gilliam implies that such a government could exist without its citizens staging an armed revolt. I'm usually willing to suspend disbelief, but this goes too entirely too far.

Despite the description, Brazil is not a documentary. It's not even political, at least not the way most dystopian works are. Instead, it's a critique of bureaucracy in the broadest possible sense. Critics who don't read Brazil as a critique of their least favorite political system tend to say it's about the power of dreams to conquer oppression. But that misses the point, too. In Brazil, fantasy is dangerous. Not because it's dangerous to institutions, or the system, or whatever else you might have been coached to expect in this kind of movie. No, pretty much because it's a hopelessly inadequate weapon against even the most incompetent power structure. Oh, the other thing about Brazil: it's a comedy.

Jonathan Pryce plays Sam Lowry, an anonymous functionary rotting away in a dead-end government job. The poster he's unconsciously mimicking is out of focus by the time he steps into the frame, but it reads, "HELP The Ministry of Information HELP YOU." It's instructive to note what kinds of governments actually have Ministries of Information. Sam works for the bad guys, but in his defense, he doesn't work very hard for them. He's found a way to be part of the system while doing as little damage as possible; the classic go-along-to-get-along guy. He's a clerk with the Department of Records, as far from the bright center of the universe as possible. Brazil opens with a horrifying scene of an official abduction at Christmastime. Stormtroopers in gas masks burst in through the doors, windows, and ceiling of a poor family's home, wrap the man in a burlap sack, read a scripted arrest notification ("Mr. Buttle... has been invited to assist the Ministry of Information with certain enquiries...") and bundle him off.

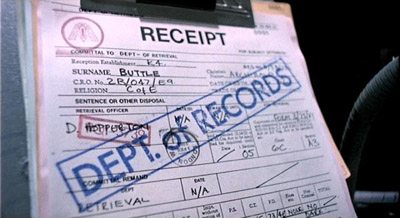

Sam Lowry is aware of the scene above—the terrified wife, the screaming children, the officer in a bowler, the uniformed thugs—but by the time it's brought to his attention, this is what it looks like:

That's the Department of Records's copy of the Ministry of Information's receipt for Mrs. Buttle's receipt for her husband. Unfortunately for nearly everyone in the movie, the Ministry of Information should have picked up Archibald Tuttle, not Archibald Buttle. This error is what pushes Sam out of his cocoon of paperwork and into the horrors that surround him. But the mechanics of the plot aren't what makes Brazil a great movie. It functions best as an essay about the way power systems force people into passive-aggressive relationships with each other. In this sense, Gilliam's movie is closer to Rousseau than Orwell.

There are three standout performances that show different ways of peaceful coexistence with a beast like the Ministry of Information, ranging from the comic to the horrifying. Most passive is Ian Holm's performance as the head of the Department of Records, Mr. Kurtzmann, who is the petty tyrant his name (short-man) implies.

Kurtzmann is an incompetent, effete paranoiac. But he's better equipped for survival than Sam; he knows how to avoid being held accountable. Kurtzmann and Sam's relationship will be immediately familiar to anyone who's had a boss who knew less than they did. But as the film progresses, Kurtzmann looks smarter and smarter; his incompetence is a shield.

Less funny and more threatening are Bob Hoskins and Derrick O'Connor as Spoor and Dowser, two duct repairmen from Central Services whose battle with Sam over the repair of his ducts is a major sideplot.

Bob Hoskins, as you'll note from his smile, is in full The Long Good Friday mode; nobody to fuck with. Sam Lowry calls these guys in when the air conditioning at his apartment breaks. Once he pisses them off (by having the system fixed by an off-the-books repairman), they do everything they can to torment him. The beautiful part is that they do it all by the book, filling out all the necessary paperwork as they tear his apartment to bits. By the end of the movie, all Lowry's possessions are dripping icicles as Spoor and Dowser hang out in environmental suits. This is the definitive portrait of aggrieved functionaries, using every bit of their limited power to fuck things up.

The most horrifying character in Brazil, however, is also the best family man in the movie, filled with bonhomie and good intentions. This is Michael Palin, playing Sam's oldest friend, Jack Lint. He has a beautiful wife and adorable triplet daughters. He also works for the Department of Information Retrieval, on the top floors of the Ministry of Information, where he tortures people to death for a living. It doesn't seem to bother him much.

You don't get the impression that Kurtzmann or Spoor or Dowser think too much about what they do for a living. Lint's different; he believes he's fighting the good fight. "Our job is to trace the connections and reveal them," he tells Sam. But Jack can't afford to draw any connections between what he does for a living and the kind of person he imagines himself to be, and his cognitive dissonance is the moral abyss at the center of the movie. A system like the Ministry of Information requires thousands of Jack Lints, each more interested in their daughter's latest exploits than the bloody handprints on their shirts. Casting Michael Palin in this role was a brilliant move on Gilliam's part—not only is Palin naturally affable, but the audience has been coached by Palin's work with Monty Python to expect him to be funny.

Which is not to say Brazil isn't funny, but it's darker than a black comedy. Call it a black hole comedy; no light escapes. Katherine Helmond and Jim Broadbent turn in great performances as Sam's mother and her plastic surgeon; here they are at a post-op celebratory party. Note how plastic Broadbent's face is here.

This party scene is actually the one moment in the movie that's almost entirely comic. Kathryn Pogson, playing a young woman Sam's mother is trying to set him up with, does a bit of physical comedy that's absolutely first-rate. And if you can watch Jonathan Pryce's eyes during his conversation with Jack Lint and his wife without cracking up, you're a better man than I. But the party is also where Sam definitively sticks his head above ground, accepting a promotion from the Department of Records into Information Retrieval. From here on out, Sam's part of the moral, spiritual, and even architectural emptiness that's at the heart of this world. Here's the entrance to Information Retrieval.

There's a straight line from those doors to the movie's heart of darkness, which makes Room 101 look like Candyland.

It's worth noting at this point that the highest ranking official who's ever mentioned in the movie is the deputy minister. Nobody's behind the controls. And the most dangerous thing in a system like that is believing you can make a difference. Which brings us to Sam's daydreams.

Sam thinks of himself as a movie star hero, an angel with metal wings and facepaint:

Obviously, this bit of costume design hasn't aged as well as the rest of the film, but it's clear that Lowry's ideas of heroism come from the movies. His apartment, unlike anyone else's, is decorated with film posters, and at one point, looking for a conversation ender, he steals a line (inappropriately) from Casablanca. That's a significant movie to choose, because Rick Blaine is the definitive Hollywood portrayal of what Jim Shepard calls "the hero in disguise." Here's Shepard's description of Blaine:

No one in Casablanca...is at all surprised when Bogart's Rick throws self-interest out the window in favor of the underdog and duty. Sure: Rick may talk like an isolationist for three-quarters of the movie. But when the chips are down...

Part of the fun of Casablanca is waiting for Rick to inevitably become a hero. But waiting for Sam Lowry to try to make the same move is more like watching a babysitter in a slasher film set out to explore the dark basement. At the beginning of the movie, daydreams provide Sam with some respite from the awfulness around him, and that's all they do. It's once he convinces himself that he really is the kind of hero he dreams about, and tries to assume that mantle, that things go terribly wrong for him. At the film's end, he's still relying on fantasy as a shield from the horribleness of his existence, but his existence is orders of magnitude more horrible and he's gotten everyone he cares about killed. So to me, to the extent the movie was about fantasy at all, it was about the danger of confusing fantasy with the real world. From my perspective, Sam's dreams are no more important than Kurtzmann's incompetence, or Spoor and Dowser's petty triumphs; just another way to bear the unbearable. And maybe a riskier coping mechanism than anyone else's, at least in the Ministry of Information. Dreams don't leave a paper trail.

Randoms:

- As you can tell from the stills above, James Acheson's costume design is a film noir lover's wet dream. Note especially the jump from the late 30's to the mid-50's for the formalwear at Sam's mother's party. As if the rich can afford to live fifteen years or so in the future. Which they more or less can.

- As great as the costume design is, it has nothing on Norman Garwood's production design. Just a few examples; virtually every frame of the movie is packed with brilliant work. First, here's the Ministry of Information's logo, featured on every one of the billions of pieces of paperwork that litter the movie:

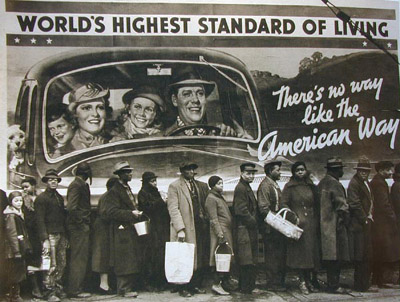

- Note how busy and overdesigned the logo is, and yet how immediately recognizable. Much simpler in terms of graphic design are the propaganda posters that cover the walls. You can see one in the first still above, but there are more than twenty. My personal favorite is the one that reads "DON'T SUSPECT A FRIEND...REPORT HIM!" But for sheer design genius, it's hard to beat this:

- Which is a modified version of a piece of billboard art that Margaret Bourke-White captured on film in the 30s:

- Notice how much meaner the kids look in Brazil's version. Last, here's the film's version of the open road, offered as a bracing tonic to the overcrowded squalor of the cities:

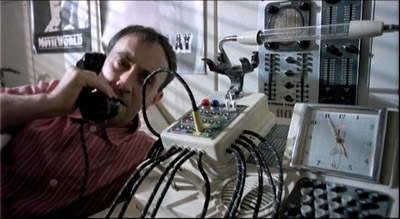

- One thing Brazil has in common with 1984 is the overall shoddiness of their worlds. Remember Victory Gin? Well, the food in Brazil doesn't seem so great either, but it's the industrial design that's really appalling. Here's a telephone:

- To talk, you simply put the right cables in the right plugholes. It's as easy as making calls with CINCO. And here's a computer:

- Both devices are as user-unfriendly as it's possible to imagine. Nothing in Brazil works right, and even the East Germans designed better looking technology. You can see the Ministry of Information logo on the filing cabinet in the background, looking more than a little like a Masonic compass and square. (Blake would have loved this movie, I'm convinced). By the way, that's co-screenwriter Charles McKeown on the left, playing a character named Harvey Lime. Is the name a clue that he's in charge of the whole show? Almost certainly not.

- Two more cameos: the technician at the film's opening is Ray Cooper, who worked on the score with Michael Kamen and my roommate tells me is Elton John's percussionist. And it's not really a cameo but I would be a jerk not to mention Robert De Niro's role as renegade duct repairman Harry Tuttle. De Niro apparently spent a great deal of time researching his part, much to the annoyance of the rest of the cast and crew.

- A word about the score Cooper helped with: it's brilliant. It's based on Ary Barroso's "Aquarela do Brasil," a masterpiece of cheesy lounge music. Gilliam's original idea for the movie came to him from a single mental image: a man sitting on a beach dyed black with coal dust, surrounded by industrial wreckage, listening on a staticky radio to an old song that promised exotic escape. "Aquarela do Brasil," (or to be precise, the worst English versions he could find) was what he settled on. Kamen hated the song, and tried to get Gilliam into Luiz Bonfá and Antonio Carlos Jobim, but to no avail. Gilliam wanted "Brazil," and Kamen rose to the challenge. Virtually every cue takes something from the song; all of them are good and some are transcendent. My personal favorites are the music under the tracking shot through the Department of Records (a particularly manic arrangement designed to mimic typewriters) and the cue during Harry Tuttle's burial by paperwork (Harry Tuttle's theme comes back in a minor key and is gradually overshadowed by the bass line from "Brazil," newly ominous). Also, I defy anyone who has noticed that Harry Tuttle's theme can be sung "Haaaaaaaaaaarry Tuttle!" to not think of that whenever his horns come in. Finally, it should be noted that the samba-with-children's choir version of "Brazil" that closes the movie is a direct allusion to the end of Black Orpheus, but kind of a sick joke, given the difference in tone between the two endings. Bonfá and Jobim redefined movie music, so Kamen returns the favor by redefining Bonfá and Jobim.

- The film isn't kind to women. Besides Sam's nightmare of a mother, the only other major female character is Jill Layton, who we know just about nothing about that isn't filtered through Sam's fantasies.

- Reportedly, Jill had a larger role in the script, but was scaled way back because Gilliam wasn't happy with Kim Griest's performance. I suspect she would have been cut back anyway; the film is already overcrowded.

- Not as overcrowded as the Criterion Collection DVD edition, however. At three disks, this is the largest set so far (and the reason for the gap between the last movie and this one). Watching And The Ship Sails On, I wished for more special features. Well, like the man says, everyone gets everything he wants. Brazil was the subject of an epic battle between Universal's Sid Sheinberg and Terry Gilliam; Sheinberg wanted cuts made to the movie and Gilliam wouldn't make them. Usually, these arguments are very private; Gilliam made this one personal and public, appearing on the Today Show with a glossy photo of Sheinberg and taking out a full page ad in Variety ("Dear Sid, When are you going to release my movie, Brazil?") Eventually, Sheinberg brought in a team of ringers to recut the movie; the third disk of this set is the U.S. television version, believed to have been made from Sheinberg's cut. It's excruciatingly bad, but worth watching to see how the same raw footage can be used to produce a work that's entirely different in tone and effect. Anyway, this movie chronicles parts of the production process that most DVDs ignore completely. Which is great—but don't think you're going to get through it in a weekend. If two commentary tracks, the two cuts of the film, and an entire disc devoted to production details isn't enough to keep you busy, you can always buy Jack Mathew's book.

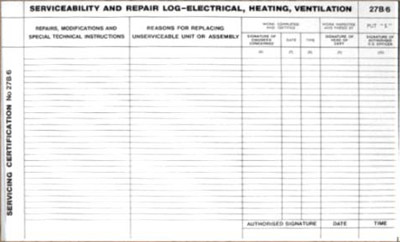

- Confidential to any Central Services employees: here's form 27B-6. Keep a few copies with you; you'll need them.

- Wired magazine runs a blog on "Privacy, Security, and Crime online" that's an invaluable resource if you're interested in those things. Although the blog's name is now officially Threat Level, fans of Brazil will enjoy its original name, still part of its URL.

- The highlight of the second disc, to me, was the section on various drafts of the screenplay. As a screenwriter, it's incredibly reassuring to see the missteps that even writers like Tom Stoppard make between the initial concept for a film and a polished shooting script. To put a complicated process in a few words, it's about simplifying and streamlining, getting as few characters as possible to do as much as you can. In this case, early drafts featured no link between Buttle and Tuttle (that was Stoppard's great structural contribution). Having Jack Lint be the man who'd interrogated Buttle was a third or fourth draft simplification, one that it's difficult to imagine the movie working well without. Before then, he was Lowry's friend, but played no real role in the plot. Oh, one more thing to learn from the screenplay section: DON'T PISS OFF TOM STOPPARD. Here's how Terry Gilliam describes the differences of opinion that led them to stop working together:

There would be areas where I just didn't agree with what he was doing, I didn't get it, it was too intellectual or too, I guess, clever, as opposed to emotional.

Now here's how Stoppard describes the same problems:What I recall in a general way is that, because as I remarked before, Terry wasn't principally interested in verbal humor, or indeed in words—I really don't believe he's that interested in dialogue as a craft—sometimes he wouldn't understand a joke, perhaps, and it's incredibly difficult to explain a joke to somebody who simply doesn't understand it. There's a line somewhere in the film where Michael... Jonathan Pryce meets Michael Palin somewhere and he says, "Hello! How are the twins?" and Palin says, "Triplets," and Sam [Michael] says, "Oh, how time flies!" Terry was completely bewildered by this, and also I was completely incapable at explaining why it was a joke at all. It is in the movie, I believe. And there's a scene where the mother, who's fairly hideous—no, that's perhaps unfair—but the mother is having plastic surgery of some kind. And halfway through the process one sees her looking, you know, quite repellent. And the doctor's saying, "There you are! Already she's twice as beautiful as before!" And the son looks at her and says, "My God, it works!" Terry didn't... Terry had difficulty understanding, and in fact I think he cut that out, and then later he got it, and tried to put it back and perhaps succeeded in putting it back.

I would rather not have Stoppard running around saying on the record that I was a dolt who couldn't get a joke, much less a writer who was not interested in words. By the way, Gilliam cut that "My God, it works!" line out of the Criterion edition.

- There are four different cuts of this movie: a European theatrical cut, the U.S. theatrical version, the television syndication cut, and the Criterion edition's director's cut. I know that I've seen the U.S. theatrical version (which I think is the only one that has the "My God, it works!" line—although the TV version does have Sam say, "My gosh, it works") but I don't know where I might have seen it. Maybe on a 16mm print in college; it's also possible that the VHS version was this cut. It's not available on DVD, though; the Universal DVD is the same cut and transfer as the Criterion edition, but without any of the extras. So we'll all have to wait for the twenty-five disc definitive Criterion reissue to see that version again.

- Finding political parallels between this movie and the present day is a first-paragraph-only kind of exercise. But it's also a last-bullet-point exercise. I feel like the world has moved further from 1984 and Brave New World. And certainly Alphaville seems quaint. Brazil? Not so much. An exchange from the screenplay that didn't end up in the movie:

JILL

Don't you know the sort of thing

that Information Retrieval does?

SAM

What do you mean? Would you rather

have terrorists?

JILL

We've got both.

- Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Brazil.