Autumn Sonata, 1978, written and directed by Ingmar Bergman.

Philip Larkin doesn't get a credit on Autumn Sonata, but the movie does seem at times like it was adapted from "This Be The Verse." That's the one that starts like this:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Bergman's movie doesn't start with the same jolt Larkin's poem does. You would be forgiven for believing it to be much more sentimental from the opening sequence, a reunion between a mother and daughter.

They seem happy to see each other, and in the moment, they probably are. That's the last exterior shot until nearly the very end of the film, however; from here on out it's all interiors. If that sounds claustrophobic, it is. If it doesn't sound all that cinematic, it's not. Autumn Sonata has more in common with theater than film, from the limited number of locations to the soliloquies to the lengthy aside from Halvar Björk that begins the film.

I can't remember the last film I saw that was so play-like. What's more, Autumn Sonata's progenitors are not the kind of plays that people imitate for films these days. Think about it: when's the last time you heard someone describe a movie as "Strindbergian?" People adapt Miss Julie for film every ten years, but writing something new in that vein takes a special kind of madness. Which Ingmar Bergman apparently has in spades.

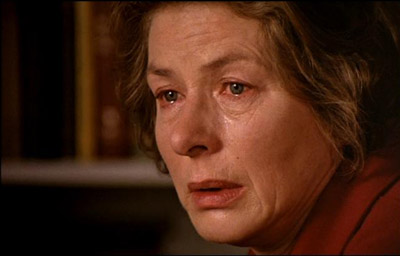

Bergman takes a lot from Strindberg, from the Norwegian setting to the structure of steadily escalating secrets and revelations. He even has his characters spend all night over a bottle of wine, like in Miss Julie. But he also has tools Strindberg never did. Most of the time, when talking about the difference between film and theater, we're talking about things like camera movement or special effects. Which leaves out the dramatic power of a merciless close-up.

That wouldn't really play in theater, even on a very small stage. Of course, half the reason that close-up is so hard to take is because that's not just any face, that's Ingrid Bergman. You know, Ingrid Bergman:

Casting a star like Bergman in a naturalistic drama like this one has a certain perverse genius to it, particularly in the part of Charlotte. Ingrid Bergman seems a little out of place, a little too theatrical, like casting Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard. (Of course Ingrid Bergman only looks a little overdramatic when compared to the cast of an Ingmar Bergman movie—to seem overdramatic compared to the cast of a Billy Wilder movie is a different thing entirely). But Charlotte, like Norma Desmond, is both overtly theatrical and past her prime. As a young woman (and as a middle-aged woman, and as an old woman), she neglected her husband and daughter for the demands of her profession as a concert pianist. As the movie plays out, she is called to account by her daughter, Eva, played by Liv Ullmann. At the opening of the film, she comes across as something of a milquetoast:

Shortly after her mother's arrival, however, she has a conversation with her husband that shows just how much anger she's got stored up inside her. Her husband (a pastor) tells her, not really thinking about it, that he "longs for" her. She replies:

Those are very pretty words. Words that don't mean anything real. I was brought up with beautiful words. Mama is never furious or disappointed or unhappy. She is pained. You have a lot of words like that too. It's a kind of occupational disease. If you long for me when I'm here, I begin to be suspicious.

You have to be careful about people who can't take a compliment. In a lot of ways, the point of Autumn Sonata is a series of revelations about just how damaged and angry Eva and Charlotte both are.

Which is to say nothing of Helena, the truly damaged member of the family. Eva keeps her in an upstairs room, which is not as cruel as it initially sounds, given that Charlotte had sent her to a home (and not seen her for six years at the beginning of the film). She's suffering from some sort of degenerative nerve disease, and serves as a sort of inarticulate symbol of the rotting mother-daughter bond downstairs.

The days are pretty much gone when you can use someone with a handicap as a symbol in a movie, too (unless he or she is a symbol of "triumph over adversity"). But Helena's nearly incomprehensible shrieks of anger and fear when she realizes her mother has left again seem like Eva's id made flesh, not like a separate character. Anytime Helena is on screen, things tend to be uncomfortable and unpleasant. And in fact, her very existence is the first nasty surprise for viewers, and for Charlotte. Eva doesn't tell her mother that Helena is now living there until she has unpacked. She says she didn't tell because Charlotte wouldn't have come to visit if she had known; but shortly thereafter she takes real pleasure in telling her husband how hard Charlotte tried not to look rattled when Helena's name was mentioned.

But if Eva has to plant little traps to make Charlotte feel miserable, Charlotte just has to be herself . There's a telling moment early in the film where Eva shyly tells her mother that she's recently given a small recital. Almost without thinking of it, (and in a tone that says nothing more aggressive than, "Well, what a coincidence! I've done something like that recently myself!") Charlotte tells her that she's just held a series of sold-out shows for schoolchildren in Los Angeles.

There's a special hell for children of very talented parents. In the film's most remarkable sequence, Charlotte, trying to be gracious (at least on the surface), sees sheet music for Chopin's preludes and asks Eva to play for her. Eva demurs at first, but then sits down and plays his Prelude in A Minor. While she's playing we stay on a tight closeup of Charlotte watching her. She's brought to tears by Eva's playing, but when Eva asks her if she liked it, she answers "I liked you." That's not good enough for Eva, and she presses the subject. Charlotte won't answer at first, but when she does, she has an answer all ready, saying, as she walks to the piano, "Your technique wasn't at all bad, though you might have taken more interest in Cortot's fingering. But let's just talk about the conception." After giving Eva a harsh speech about her concept of the Preludes (among her constructive criticisms: "Chopin was not a mawkish old woman!"), Charlotte plays her version of the Prelude. I've never seen a filmmaker ask the audience to tell the difference between competent and brilliant playing (especially in classical music), but Bergman has us listen to both versions in their entirety. It's a crazy move but it works; the difference is striking. While Charlotte plays, the camera stays still and we see a lifetime of never being quite good enough for her mother flash across Eva's face. It's devastating.

Both Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Bergman give amazing performances throughout, which is especially important in the film's third act (or movement, if you want to think of it as a sonata). As Eva gradually lets more of her rage show, and Charlotte is able to hide less and less of her guilt and fear, we enter territory that could easily stray into melodrama. In fact, on the page, I think this section of the script reads terribly. But Ullmann and Bergman keep things real; Ullmann in particular is frighteningly believable.

As Eva changes during this act from milquetoast to Charlotte's tormentor and accuser, permanently aggrieved, I thought less of Strindberg and more of Harold Pinter. Eva would be right at home in Old Times. Towards the end of the film, Eva asks her mother, "Is my grief your secret pleasure?" That question, the film suggests, is at the heart of any parent-child relationship, and it goes both ways. Its answer, for Ingmar Bergman, is yes.

Randoms:

- I liked this so much better than The Seventh Seal it's not even funny. Between these movies, Ingmar Bergman learned how to explore abstract themes without making abstract movies. Eva, Charlotte, and Helena may be archetypical figures, but they're also real and recognizable people.

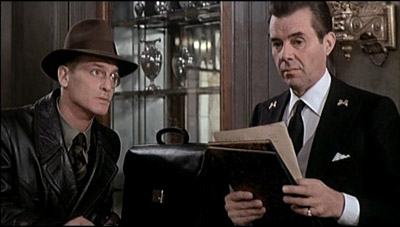

- If the main movie seems play-like, it has nothing on the flashback sequences, which literally look like they're taking place on a stage. Here's a representative sample:

- Again, there's a nearly completely static camera for these sequences. Bergman stages these sequences like this because he believes we remember things this way, as though they took place on stage.

- I stand by my previous assertion that Ingmar Bergman would have been an incredible horror director and offer as further evidence the brief nightmare sequence in Autumn Sonata. But since I liked Autumn Sonata, I no longer think of this as a great loss for the horror industry.

- I imagine that not too many interviewers asked Ingrid Bergman that classic of lazy press junket journalism, "So how much like your character are you?" Bergman, like Charlotte, abandoned husband and child for a lover (in her case it was Roberto Rossellini, and it was a very public scandal). I suspect that the personal resonances of the script have a lot to do with Ingrid Bergman's near-perfect performance in this film. It came with a lot of struggle, though: the two Bergmans argued constantly during the production. Peter Cowie relays a story on the commentary track about an excruciating table read which Ingrid performed 40's style, complete with florid intonation, reducing the rest of the cast and crew to despair. But what actually ended up on film is nearly perfectly pitched; Bergman's excesses match with Charlotte's theatricality.

Update (9-22-06):

Sven Nykvist, D.P. on Autumn Sonata and many of Bergman's other films, died the day I posted this. Which makes me feel awful for not mentioning how beautifully it was shot and lit. Nykvist has no fewer than ten films in the Criterion Collection, most with Bergman. The only one I've seen so far besides Autumn Sonata is The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which also features fantastic cinematography.

Update (8-1-07):

Bergman has joined Nykvist. Autumn Sonata was my favorite of his films that I've seen so far, so this is where I'll note this. For an interesting look at his films from Viktor Morton, see here.