For All Mankind, 1989, directed by Al Reinert.

In the "America in the 60's" montage that used to play in my head when someone mentioned the era, the moon landing got about five seconds. And you know exactly what five seconds they were; the blurry television feed we've all seen of Neil Armstrong dropping the last few feet to the moon's surface.

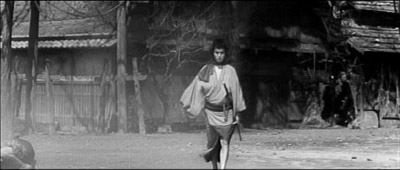

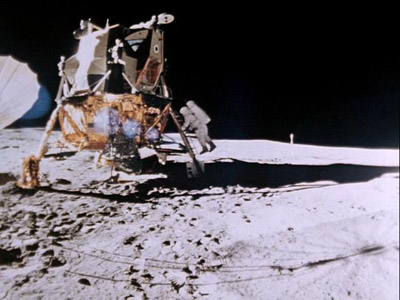

Altamont got more screen time than Neil, because Gimme Shelter isn't grainy video footage. But it turns out that the astronauts shot on film, too, and For All Mankind is Al Reinert's painstaking compilation of that footage. Here, for example, is a still from the movie of Alan Bean taking his first steps on the moon (during the second moon landing):

That's a little bit better looking, even with the lens flare, no? For All Mankind pretty definitively replaced that grainy footage of Armstrong with much stranger, much more haunting imagery.

Reinert's film is not a traditional documentary by any stretch of the imagination. The movie opens with the following titles:

During the four years between December 1968 and November 1972, there were nine manned flights to the Moon.

Twenty-four men made the journey. They were the first human beings to leave the planet Earth for another world.

This is the film they brought back...

...and these are their words.

That's all the context For All Mankind gives you; there's no stentorian narrator or subtitles identifying who or what you're seeing. Which is still not that strange for a documentary, although it's rare for a documentary about science, history, or both. In a typical vérité documentary, however, the filmmakers usually go for the appearance of unmediated reality; events in the order they actually happened. Reinert's movie isn't like that. Instead of presenting a history of the Apollo program, or profiles of the men who made it happen, his movie is a string of basically contextless images accompanied by sound from interviews with the (unidentified) Apollo astronauts. They've been edited together not in chronological order, but into a sort of composite moon mission, from liftoff to splashdown, that uses footage from all nine missions (and other missions entirely). So, for example, you might see a shot of the Apollo 17 astronauts boarding an elevator and cut to the Apollo 16 astronauts exiting the same elevator eight months earlier. I've never seen a documentary entirely like this one; it's not based on the facts so much as a subjective recreation of a moon mission.

Reinert's style has implications both good and bad. On the positive side of the scale, he is able to use the best possible shots of any stage of a moon mission he wants to show. On the negative side, jumping around in time means there's very little room for character. The astronauts blur into a kind of composite person, as do the NASA employees in Mission Control; there's very little human interest in the movie as a whole. What's strange is that I enjoyed it; my taste in documentaries usually runs to work that's exclusively human interest (Errol Morris, for example). I'll make an exception to that rule in the case of For All Mankind, because the footage Reinert uses is so strange and beautiful. For me, a lot of the pleasure of this movie came from the unexpected details, like the ice falling off the outside of the Saturn V rocket during launch.

In retrospect, it seems obvious that a rocket that carries vast quantities of liquid oxygen and hydrogen would quickly be covered with frozen condensation, but I hadn't put together what that would actually mean until I saw For All Mankind's footage of ice dropping from the rocket into the inferno beneath its engines.

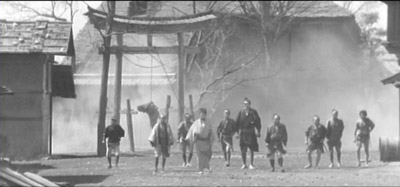

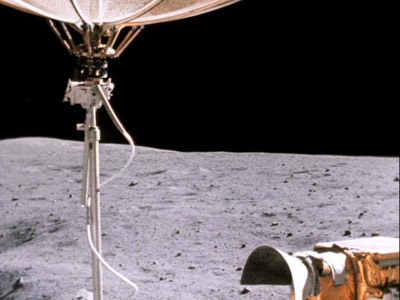

Another obvious-in-retrospect detail is the way lighting works in a vacuum. On Earth, objects have a certain warmth that I guess comes from light hitting the never-wholly-transparent atmosphere. Which isn't something that's noticeable at all until you see film shot on the surface of the moon:

Look at the absolute blackness of the sky in contrast to the brightly-lit surface: this is lunar day. But there's nothing above the surface to diffuse the light, so the sky is pitch black. You can't really see the effect on video footage, but on film I found this combination of harsh sunlight and absolute darkness endlessly fascinating.

More familiar, but just as striking, are the film's images of earth from space. I think everyone's been overexposed to these images, but they're worth reconsidering anew. For example, look at the strange glow the clouds have here:

Perhaps part of the beauty I rediscovered in these images came from seeing them as motion footage instead of stills; perhaps it was Brian Eno's excellent score; perhaps it was seeing them in the context of what it took to bring this footage back. But I found myself moved by even old chestnuts like this shot of the earth (which I saw every day for a year; it was on the cover of one of my high school textbooks):

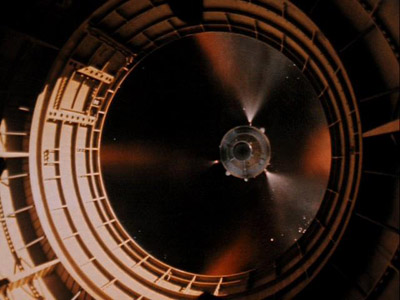

Part of it is certainly presentation; Reinert blew everything up from 16mm to 35mm, and corrected for camera jitter and film speed (it was shot with variable speed cameras, usually at speeds slower than 24 fps). None of these images have ever looked better. And some of them had never been seen before, as in the following two shots of rocket stages separating:

Now that's camerawork even Bruckheimer would have a difficult time recreating. As you can see, in the first shot the camera is outside the top part of the rocket—and in the second shot we're looking up from inside a lower stage as it begins spiraling back to earth. Which raises the question of how this could possibly have been shot; the answer is weirder than the footage itself. The cameras that shot this were designed to burn up on reentry, just like the rocket stages they were attached to, but not before they ejected their heat-shielded, parachute equipped film canisters. The exposed film was then caught in mid-air by C-130 transport planes dragging huge nets behind them. The idea was to let engineers study the film if anything went wrong with staging. Given the exceptional quality of these images, and the extraordinary effort required to bring them back to earth, it seems churlish to criticize Reinert for presenting them as though they are from a moon mission (they're actually from an unmanned Saturn V test flight, as he explains on the commentary).

In fact, For All Mankind is filled with footage that's not what it seems to be: the trans-lunar burn is actually reentry footage, all the spacewalk footage is from Gemini missions, and of course the moon-landing footage was shot on a sound stage in Arizona. Well, I'm just kidding about the last one (I think), but there are enough misrepresentations in the movie to give the people who pick apart Michael Moore's films years of work to do. Reinert points them out on the commentary track, as well as his reasons for using footage from other missions where he did. The spacewalk footage, for example, is from the Gemini missions because those rockets had larger windows (Reinert uses this point in the commentary to rail, amusingly, against the tiny windows on the Space Shuttle). The commentary is interesting, because it's obvious Reinart is remarkably unconcerned with accuracy (even going so far as to stage a shot of the moon through an Apollo command module window). His goal, instead, is to produce something much more subjective than a standard documentary. And that's what the subject demands; we've all seen enough photos from space that only a radical recontextualization like this film can command our attention.

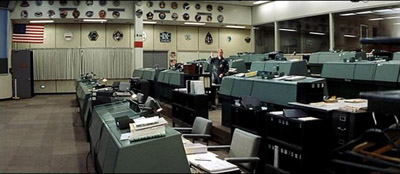

So far, I've written about For All Mankind as though it was as arid and alien as the moon itself. This isn't entirely true. Reinert includes a lot of footage of Mission Control, and interesting human and period details creep in almost despite the way the film is cut. You do see the stereotypical NASA employees with crewcuts, looking sternly at monitors, as in a thousand movies:

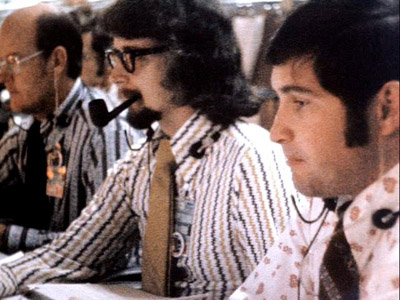

But there are things about Mission Control that have somehow not made it into the collective unconscious. For one thing, everyone smokes. For another, the NASA dress code was a little more lax by the end of the program:

Coolest. Mission Control Guy. Ever. The footage of the astronauts themselves is less interesting; once you've seen one guy do a zero-g somersault you've pretty much seen them all. There's an interesting section about the music the astronauts took with them: Reinert includes Buck Owens and Merle Haggard on the soundtrack, with recordings that seem to have been made especially for the Apollo astronauts. Other than that, however, since the film gives you next to no information about the astronauts you're seeing, the sections inside the ship didn't do much for me. And unfortunately, the voiceover doesn't have a lot to recommend it either.

There's one exception, an account of a dream one of the astronauts had about finding a pair of astronaut doppelgängers on the moon, in identical space suits, who'd been there for thousands of years. Reinert pairs this with a particularly haunting cue from Brian Eno, and footage from a rover of the empty lunar surface. It's a moment where the whole film comes together, and you're forcefully hit with the weirdness of the whole thing. Nearly 40 years ago, we shot men in rockets to the moon. Then we stopped. Reinert tells you very little about why we did this. But with such a unique moment in human history, having a record of what it looked like is invaluable. That's what For All Mankind provides.

Randoms:

- All was not fun and games for the bearded, long haired hippies running Mission Control, as this still chillingly reveals:

- Only a space program run by an ex-Nazi like von Braun would feed its employees Cremora.

- For All Mankind has one of the weirdest special features ever: a gallery of astronaut Alan Bean's paintings of the space program. Here, for example, is a painting entitled "America's Team... We're #1":

- The DVD has no fewer than 24 of these paintings, each with audio commentary.

- The DVD also features launch footage of each of the precursor rockets to the Saturn V. For the record, that's the Mercury Redstone, the Mercury Atlas, the Gemini Titan, and the Saturn 1B. My dad had models of all of these in his childhood room; I hadn't thought of them since I was eleven or twelve, but when I was little I used to love taking apart the stages of the Saturn V model. Not that that's of much interest to anyone but me.

- There's just a little bit of the Apollo 13 near-disaster in For All Mankind, and like most of what you see, it's presented without context or explanation. Al Reinert returned to the topic later, however; he went on to write the screenplay for Apollo 13 (with William Broyles Jr., from Jim Lovell and Jeffery Kluger's book Lost Moon) .

- For All Mankind is the second Criterion film to use NASA's actual Mission Control room as a location. Here's Mission Control launching men to the moon:

- And here's the same room launching Owen Wilson into the hearts of moviegoers everywhere:

- I'm not sure which mission accomplished more for humanity, but even with Michael Bay at the helm, Armageddon cost less.