And the Ship Sails On, 1984, directed by Federico Fellini, written by Federico Fellini and Tonino Guerra.

The tenth literary rule Mark Twain accused James Fenimore Cooper of breaking in "James Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses" goes like this:

...the author shall make the reader feel a deep interest in the personages of his tale and in their fate; and... he shall make the reader love the good people in the tale and hate the bad ones. But the reader of the "Deerslayer" tale dislikes the good people in it, is indifferent to the others, and wishes they would all get drowned together.

Well, one thing you can say about And the Ship Sails On: Fellini may have broken Rule 10, but at least he gave me what I was wishing for. I tried to like this movie. I saw it several times. I read everything I could find about it. But it seems to be the work of a different director than Nights of Cabiria, and not a better one.

And the Ship Sails On is the story of a doomed ocean liner travelling through the Mediterranean during July of 1914. Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated on June 28 of that year; the first armed clashes of World War I took place in early August. So the action of the movie takes place in the lull as Europe geared up to tear itself to shreds. Until the last third of the movie, however, history barely impinges on the quotidian concerns of the aristocratic passengers. The purpose of their voyage is to scatter the ashes of a recently deceased operatic diva near the island where she was born. Most of the passengers are connected in some way or another to the world of music, with two exceptions. The first is a journalist named Orlando, played by Freddie Jones (who you probably recognize from many of David Lynch's movies):

Orlando serves as the audience's guide to the dozens of characters on board the ship; he's there because he's making some sort of documentary about the voyage. Sometimes he is accompanied by a cameraman, sometimes he just addresses Fellini's camera. When Orlando addresses the camera (as he does quite often), you're rarely sure whether Orlando is breaking the fourth wall or just talking to his cameraman. The idea of a talking-head-style journalist in the silent era is one of the better jokes in the movie, but I found Orlando's asides more distracting than effective, not least because of the constant blurring of the real asides with narration that happens within the world of the movie. Fellini actually opens with this kind of blurring: the initial footage is scratchy and silent, complete with intertitles, and people react to the camera like the novelty it is:

But before Fellini switches from silent footage, we see the cameraman and his camera; we're looking through an invisible camera as in most movies. It's playful but he keeps switching back and forth throughout the film, and you're never certain whether a character is going to react to the camera or not.

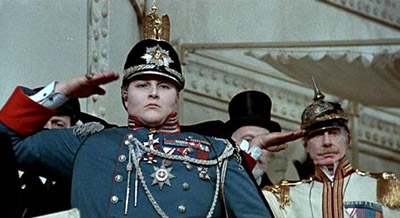

The other passenger who doesn't really belong to the world of opera is an Austrian Archduke. He's more fortunate than Franz Ferdinand, in that July of 1914 finds him still among the living, but less fortunate in that he seems about as likely to grow a mustache like Franz's as he is to grow wings. He looks like a castrato, and the few times you hear him speak about foreign policy don't inspire much confidence.

You could read the Archduke's feminine appearance as a critique of the aristocrats who were marching Europe into disaster during the time of the movie, but he doesn't look much worse than anyone else in this film. To put it bluntly, the passengers look like the walking dead throughout the movie. Here, for instance, is Shakespearean actor Barbara Jefford in a relatively recent photo:

So here's what Fellini made her look like in And the Ship Sails On.

Not a good look for her. And she's held up as the heir to the operatic throne the dead diva has recently vacated. Jefford, by the way, was stunning in the fifties and sixties, but that didn't seem a fair comparison. But in a movie where nobody looks good, nobody looks quite as bad as German dancer Pina Bausch, playing the Archduke's blind sister. Here she is, in the single least attractive kiss since The Shining:

The movie isn't easy to look at; I don't know if the quality of the transfer is responsible, but as you can see, the colors are pretty washed out. As muddy and unappealing as I found the look of the film, however, it was nowhere near as distracting as the sound. Freddie Jones speaks his lines in English, as do several other actors; they've all been dubbed in Italian with near complete indifference to the movement of his lips. Once I realized some of the actors were speaking English, I found the movie difficult to watch, because I couldn't stop lip-reading. Italian films almost never use direct sound, but if you compare five minutes of Nights of Cabiria with five minutes of And the Ship Sails On, you can immediately see the difference between good and bad postsynchronization work. This isn't strictly a function of Fellini letting his English-speaking actors act in their native tongue, either; the Italians do an excellent job of dubbing American movies so that they appear to feature direct sound.

And even if the synchronization were perfect, the sound mix would be hard to listen to. All the voices are mixed at the same level and it sounds as though at most four actors were employed. There's no variation in tone, and some of the voices (the general who accompanies the Austrians, for example) sound like nothing human. Even when the actors are clearly saying their lines in Italian, the same lines as on the audio track, the sound doesn't even come close to corresponding to the image. You can make a case that this is a Brechtian device for distancing the audience from the seductive spectacle of cinema. In fact, the rest of the movie supports this idea: Fellini deliberately uses very artificial special effects and, at the end, has the camera pull back to show the ship's deck in its stage at Cinecittà. But I'm skeptical of film analyses that make subtle virtues out of apparent shortcomings, and whether these are deliberate technique or just indifference, it made the experience of watching the movie excruciating. To me, cinema's seductive qualities are kind of the point.

But perhaps this is an unfair criticism, akin to looking for plot holes in Armageddon. As Vincent Canby (who loved the movie) pointed out, And the Ship Sails On "doesn't depend for 10 seconds on anything as conventional as identifiable characters or a narrative." And as we've seen, it also doesn't depend on technical virtuosity. What's left is something you have to watch sort of like you would a sketch comedy show; there are individual scenes and images that work, but looking for anything else will only lead to disappointment. The movie gets better toward the end, when the aristocrats' voyage is disrupted by the world outside, first in the form of Serbian refugees. The refugees look more alive than anyone on screen to that point, and they have the obligitary scene where they play music and dance with greater charm and skill than the upper classes:

That scene's a cliché, but I liked it anyway. And even the shoddy model work occasionally pays off; I liked the looks of the Austrian warship that appears to capture the Serbian refugees. It looks like an Orion-class battleship as designed by Terry Gilliam:

Note the obvious cellophane sea in that shot; actual water is a rarity in this film. And Fellini does continue to have the same talent for surrealism that characterizes his great films from the sixties. The most notable sequence of this type in And the Ship Sails On is a semi-successful attempt at bathing a rhinoceros, the ship's most unhappy passenger.

The movie's at its absolute best when Fellini is playing with the paradoxes of a media-driven life. The diva whose ashes are at the center of the story keeps getting resurrected, first by an impersonator, then by Victrola, and finally by film, coming most fully to life as the ship sinks:

But Fellini doesn't linger on this (or any of his most effective images) long enough to provoke more than a momentary pleasure in the viewer. Nights of Cabiria was a focused character study with humanity shining through in every shot; 8½ is made with a clear affection for its main character. And the Ship Sails On feels like the work of someone who has fundamentally lost interest in other people; no one but the dead diva seems human. Now I'm not opposed to detached, academic filmmaking per se, but I think for a movie in which we don't care about the characters to work, it has to be well structured and technically competent. And the Ship Sails On, I am sorry to report, struck me as neither.

Randoms:

- In all fairness, I should note that I am unqualified to judge the operatic music that's a big part of the film. As Canby points out, Fellini uses chopped bits of opera scores, with different lyrics, throughout the movie. Unfortunately, the music is not well mixed, and the new lyrics are not subtitled. The DVD features no commentary tracks, and there doesn't seem to be much criticism of the film available online. So without a better knowledge of Italian (or better hearing) than I've got, you're pretty much on your own as far as teasing out what Fellini is up to with this. I'm prepared to believe that I missed the key that would have made the movie seem brilliant to me. But I could have used more help from the DVD.

- The strangest thing about the shot where the camera pulls back to reveal the set at Cinecittà is this guy:

- Clearly recording sound during the shoot (there's a boom mike visible, as well). What did they do with these tapes? They don't seem to have been used—even as a reference—when the postsynchronization work was done.

- Like I said above, Fellini does a good job of playing around with mediated experience in this movie. Here's the thing, though: And the Ship Sails On premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September of 1983. That means it arrived seven months too late, because the February before, David Cronenberg's Videodrome was released. The two films have some of the same concerns (both even feature characters who only exist in mediated form: the diva in And the Ship Sails On and Professor O'Blivion in Videodrome). But to me Videodrome seems fresh and alive, while Fellini's film seems as antiquated as its sets.