Lord of the Flies, 1963, directed by Peter Brook, from the novel by William Golding.

On his pseudo-commentary track for Lord of the Flies,1 William Golding tells a story about a student in a creative writing class who goes to his teacher and says, "I've finished the story I was writing. Now should I go back and put the symbols in?" You can't do it that way, of course; symbols are either an organic part of your story or they're a disastrous mistake. The genius of Golding's novel (about a group of English schoolboys stranded on a desert island, if you're one of the two people on the planet who didn't read this in middle school) is that his story is perfectly coherent on a literal level. This makes it ideal for a film adaptation in a way that, say, Beloved is not. In fact, the novel is at its strongest the less it strays from the literal story, and is weaker in the places where Golding hits you over the head with the other meanings he's playing around with. Compare these two death scenes, for example. Here's Piggy's death:

The rock struck Piggy a glancing blow from chin to knee; the conch exploded into a thousand white fragments and ceased to exist. Piggy, saying nothing, with no time for even a grunt, traveled through the air sideways from the rock, turning over as he went. The rock bounded twice and was lost in the forest. Piggy fell forty feet and landed on his back across the square red rock in the sea. His head opened and stuff came out and turned red. Piggy's arms and legs twitched a bit, like a pig's after it has been killed. Then the sea breathed out again in a long, slow sigh, the water boiled white and pink over the rock; and when it went, sucking back again, the body of Piggy was gone.

And here's the death of one of the pigs Jack's hunters kill:

Here, struck down by the heat, the sow fell and the hunters hurled themselves at her. This dreadful eruption from an unknown world made her frantic; she squealed and bucked and the air was full of sweat and noise and blood and terror. Roger ran round the heap, prodding with his spear whenever pigflesh appeared. Jack was on top of the sow, stabbing downward with his knife. Roger found a lodgement for his point and began to push till he was leaning with his whole weight. The spear moved forward inch by inch and the terrified squealing became a high-pitched scream. Then Jack found the throat and the hot blood spouted over his hands. The sow collapsed under them and they were heavy and fulfilled upon her. The butterflies still danced, preoccupied in the center of the clearing.

To me, the second scene, with its Grand Guignol violence and overwritten sexual connotations ("a lodgement for his point," indeed), is mildly embarassing. Piggy's death, in contrast, is terrifying precisely because it is described matter-of-factly. "His head opened and stuff came out and turned red," is much more nightmarish than the pig's death. Peter Brook seems to have understood this difference, and the tone of his film is much closer to the first passage than the second, more cinéma vérité than Hollywood. And the more Lord of the Flies feels observed rather than staged, the more horrific it is.

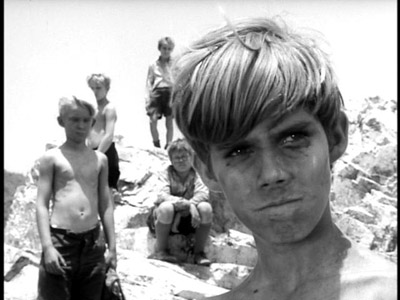

Brook does a good job, then, of mimicking Golding's style when he's at his best. He also benefits from the immediacy of film in a way Golding can't. Reading the novel, it's easy to forget just how young Golding's characters are (my memory of the novel was that the main characters were early high schoolers). In fact, however, the oldest kids would be in middle school, and the youngest are toddlers. But reading that Golding's characters are young doesn't have quite the visceral edge that, say, this does:

It's impossible to forget, watching the movie, that all of these kids are prepubescent. I also found that some scenes and images that didn't particularly stick with me while reading the novel became iconic when captured on film:

Perhaps I was a lazy reader, but I didn't realize how visually striking the choir's black robes would be against the white sand until I saw it on screen.

What's most impressive about Lord of the Flies, however, is that Brook managed to make it at all. Nearly everyone who worked on it was completely green. Tom Hollyman, the D.P., was a still photographer who had never touched a motion picture camera. Gerald Feil, the editor, had never edited anything. Peter Brook had directed film before, but had mostly worked in theater. The cast featured thirty-two children, only one of whom had ever acted in anything before. And none of the children's parents would allow them to miss a day of school, so the movie had to be completely finished over summer vacation, shooting in the middle of nowhere with infrequent access to dailies. If all that weren't enough of a challenge, Peter Brook shot it in sequence, working from the novel itself, without a formal screenplay.

As you can imagine, the results owe a great deal to luck and improvisation. I think the single best thing about this movie is the casting, done by Terry Fay and Michael McDonald. When you're casting children, you don't necessarily look for someone who's a good actor, but someone who has to do as little acting as possible to become the character you need. There's no way for a kid to do a Charlize Theron or Robert DeNiro-style body transformation, and the psychological insights a six-year-old can have into another person are, shall we say, limited. But the kids they used were perfect, start to finish. Here's the principal cast:

James Aubrey as Ralph. Simon and Piggy are visible behind him.

Aubrey's kept acting; he was in Tony Scott's Spy Game in 2001.

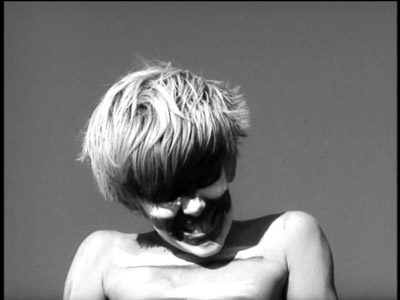

Tom Chapin as Jack.

This is the one questionable casting decision, as Chapin had lived in the United States for some time and his accent wasn't British enough; he was ultimately overdubbed by another actor. But look at that profile; that's Jack for sure.

Hugh Edwards as Piggy.

Tom Gaman as Simon, staring at the pig's head.

Even the minor characters are remarkably cast. Here's Samneric, the twins, played by David and Simon Surtees:

And this is Roger Allen Elwin (see comments for correction) as my favorite minor character, Roger, the only true sadist in the whole group:

Roger drops a boulder on Piggy.

Apparently Roger Elwin got a little too much into character; according to the commentary track he spent a good deal of the summer catching lizards and throwing them into fires.

As you can see from the stills, Fay and McDonald did an amazing job of finding the right kids for the movie. If you had a very different mental picture of any of those characters when you read the novel I'd be pretty surprised.

The movie's certainly not without its weaknesses, though, and I can't really recommend it as something to sit back and watch as pure entertainment. It was, after all, made by a bunch of first-timers with no money, and although it's better than it has any right to be, sometimes the seams show. For one thing, Brooks found it was impossible to record synchronized sound because they were shooting on the beach all the time (the sound of the waves makes recording impossible). However, he had a tight shooting schedule, such rare access to dailies, and a mortal terror that his actors' voices would change. So instead of waiting to do ADR against actual footage, he would shoot until the light faded, and then go inland with the actors and immediately record the sound for the scenes he'd just shot, relying on memory to get the timing right so he could match it with the film he'd shot earlier in the day. Needless to say, this produced mixed results, and was one of the main reasons the movie took a full year to edit. There aren't any synch issues with what you see onscreen, but the timing seems a little behind the beat throughout (timing in the "actors delivering their lines realistically" sense, not the "sound matching moving lips sense").

The sound doesn't improve much from start to finish (and maybe it's just me, but I hated Raymond Leppard's score, which really took a lot away from the movie for me). But everyone else, from the actors to the cameramen, learned how to their job better the longer they'd been doing it. And because Lord of the Flies was shot in sequence, this means that the overall quality of the movie improves the further into the story you go. The opening scenes seemed very stilted to me; it really got moving around the time Simon encounters the pig's head. In the novel, we're privy to Simon's vision, but in the film the head doesn't talk. Instead, Brook cuts back and forth between a slow push in on Simon's face (the shot of Simon above is from this sequence) and the head on its stake:

The jaunty smile on the pig's face and the buzzing flies on the soundtrack provide the same mixture of good cheer and menace that Golding gives the reader when he has the pig say, "We are going to have fun on this island. Understand? We are going to have fun on this island!" This is the first point where I thought the movie was demonstrably better than the novel, but not the last. The night of Simon's death is a particular standout. Brooks just got all the kids wound up and had two cameramen follow them around for hours as they ran amuck; the result seems like documentary footage, not a scene from a movie. Some parts of this sequence are really beautiful:

The log is the main (only?) light source in the shot, so it lights up the ocean as it flies through the air; the result is impossible to capture in a still, but it's stunning.

And some parts are terrifying:

This picture would not be out of place in Diane Arbus's portfolio.

Both of these shots, and the sequence as a whole, feel completely natural, accidental, and observed, and watching these kids completely give in to chaos is the single best part of the movie. Unfortunately it feels stilted again when Simon emerges and the kids once more have to be part of a narrative. Perhaps Brooks should have just kept the cameras rolling and let the kids do whatever they wanted all summer. As Golding understood, prepubescent boys don't need much directing to descend into chaos and cruelty.

Randoms:

- Lord of the Flies was shot with handheld Arriflex cameras, which are jittery as hell if handheld. Feil and Hollyman came up with a number of great technical solutions for problems they had working with these; the most striking is their dolly. They used model railway track and cars, camera tripods, and a gate to create something they could quickly move around the beach. What's more, the gate could be used to smoothly change from a tracking shot to a push in or out. Here it is on set:

- The first day of shooting was also the first day of the Bay of Pigs, which was not necessarily the best day to be sharing a Carribean island with a U. S. military base. Nobody knew what was going on, but they could see warships hovering off the coast all day.

- During the shoot, Brooks and his crew started getting back dailies in which every third frame or so was washed out. The laboratory kept telling them something was seriously wrong with one of their cameras, since it was flashing the negative; the crew said nothing was wrong, and they fought back and forth about this until one of the crew flew to the laboratory in New York City and observed the development process. It turned that one of the developers was smoking cigars in the lab; when he would take a drag, whatever frame was currently being processed was ruined.

- Part of Golding's commentary track is him reading excerpts from the novel; I was jolted to hear him have Piggy yell "Which is better—to be a pack of painted n-----s like you are, or to be sensible like Ralph is?" My copy of the novel (the Perigree edition, probably the one you had in school) has it as "a pack of painted Indians," and in the movie it's "a pack of painted savages." So I don't know what to believe, but I do know that Golding's original version of the line (which I think might still be around in British editions) is jarring for no good purpose.

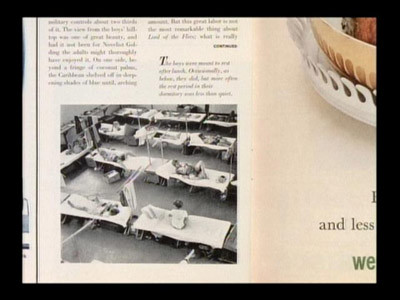

- Golding's novel has two main plot threads: the Boy's Adventure stuff of surviving on the island and the heavier descent into savagery. In the movie, the fun stuff was mostly cut out for lack of time. But the actors got to have a full on adventure of it while shooting the movie. Here's the dorm they stayed in, an abandoned factory (the picture is from a Life magazine article about the production while it was going on).:

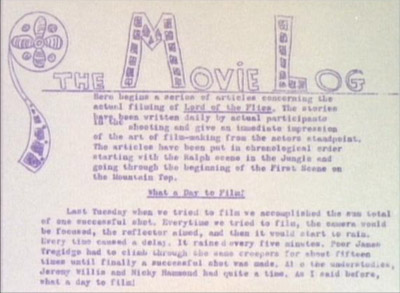

- And here's a page from the newsletter the kids wrote while shooting (mimeographed, no less!):

- When it became apparent to Brooks that the kids were bored, he gave them their own camera and let them write and direct their own movie on days they weren't on set. And when they weren't working on their own movie, they were running around on a beach, shirtless and screaming and hitting each other on camera. In short, it sounds like the best summer camp ever.

1"Pseudo" because it's a set of readings from the novel along with statements about it and—although it's been edited to overlay the same scenes in the movie—doesn't seem to have been designed with commentary in mind. Not too surprising, since it was recorded in 1976.