Fishing With John, 1992, written and directed by John Lurie.

This is the first title in the collection that's not a feature. Instead, Fishing With John is a six-episode documentary fishing show in which actor/musician John Lurie goes fishing with celebrities. At first glance, Fishing With John has everything one would expect from a fishing show: bad video cinematography, dull conversation, and most importantly, a self-important narrator who solemnly explains what we're seeing. Here, for example, is part of the narration for the first episode, in which Lurie and Jim Jarmusch go shark fishing in Montauk:

Fascinating, our world today. With technology, man now knows more about his fellow man and the world he lives in than ever before. Yet we still know very little. We know very little, for example, about the topic of today's program: the shark. The shark has lived in the same form for millions of years. The word "Shark" came from the German word "shirke," which means "villain." How deep is the ocean? Nobody really knows for sure. Today's program and fishing adventure should prove to be fun. But it could also prove to be very, very dangerous. The shark has made fatal attacks on humans in every ocean in the world. There are 27 man-eating species of sharks. When it comes to the shark, man is on his menu.

You have to imagine that paragraph read by voiceover artist Robb Webb (who you've heard in a million trailers). It's the kind of blather that I usually just tune out, but here's the thing: none of it's true. Not even close. If the idea of a documentary voiceover that's filled with lies (and not jokes, really, just lies) strikes you as funny, you'll enjoy Fishing With John. It's a case study in really stretching the disconnect between visuals and voiceover. This is not for everyone: it requires an exceptionally dry sense of humor and a lot of patience, because the show is exceptionally silly. And I have my doubts whether it qualifies as great cinema, or great television, but it's certainly unique.

A fishing show is actually kind of a brilliant setting to use for this kind of experiment, because viewers are already trained to tune out while watching fishing, particularly to the narrators, who never say much of interest. Lurie does a good job of writing narration that seems plausible just long enough to make you start to tune out; then the narrator will say something like "Both fishermen are covered with sores and boners." Which doesn't make any kind of sense at all. This is not to say that all of the jokes and silliness is in the narration; far from it. Much of the rest of the fun comes from the fact that neither the guests nor the host know anything about fishing. Here, for example, is one of the shark fishing methods Jim Jarmusch and John Lurie try:

You can probably suss out how this is supposed to work. It doesn't.

Tom Waits, on the other hand, doesn't seem like a staggeringly incompetent fisherman, but when they finally catch a red snapper, he insists on putting the fish down his pants, because it helps with his depression:

This fish is going to have a confusing last few seconds on earth.

The show is at its best, however, when Lurie doesn't play around too much with what's actually on screen and instead lets the disconnect between what we're seeing and what the narrator is describing get wider and wider. He gets better at this as the show goes along. The fourth episode, in which Lurie and Willem Dafoe go ice fishing in Maine, is the first one where he really goes crazy with this; the episode opens with both men having a good time, but not catching any fish:

then shows them gradually getting colder and hungrier, until the last shot:

Over the shot above, Robb Webb intones, "On January 19th, John Lurie and Willem Dafoe died of starvation." And that's the end of the episode. As a footnote, when John appears in the next episode, the narrator says, "John's not dead after all. My mistake."

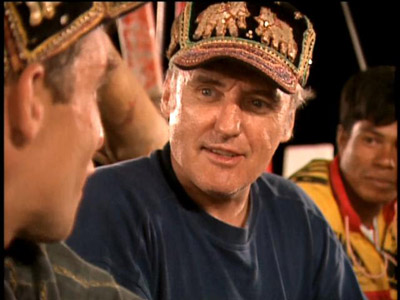

The disconnect between the narrator and what's on screen reaches its lunatic apotheosis during the last two episodes, a two-part story about fishing in Thailand with Dennis Hopper. As you can imagine, footage of Dennis Hopper fishing in Thailand is already pretty interesting, just because of how crazy and animated he is. Even in a silly hat, he looks like he could tear someone's throat out at any time:

And there aren't that many people who can tell you stories about being thrown out of Cole Porter's house for drinking too much, or give their own ideas about a sequel to Easy Rider. So Lurie could have just let those episodes stand. But instead, he has the narrator superimpose his own version of what we're seeing: John and Dennis are going fishing for giant squid. It's apparent from the visuals (no one ever mentions squid at all) that this is the narrator's own idea. A few examples:

On screen: Footage of the captain of John and Dennis's boat ringing a bell.

Narration: "On the radio, the captain has heard a hysterical SOS from a nearby vessel. He believes this can only mean one thing: a giant squid!"

On screen: John and Dennis walking into an archway, or possibly a cave.

Narration: "In these caves, it is believed there are secrets as to the habits of the giant squid!"

On screen: John and Dennis visiting a Buddhist monastary.

Narration: "John and Dennis stumble onto the sanctuary of an order of squid monks. These monks live in seclusion and study the ways of the giant squid. John and Dennis try to coax them into divulging the secrets of the giant squid, but the squid monks only acquiese to show them photographs of their families."

On screen: John and Dennis asleep in their boat.

Narration: (having previously asserted that the giant squid can "hypnotize most mammals"): "John and Dennis... have been hypnotized!"

The calm, precise way in which the narrator keeps bending what's on screen to suit his own mad narrative is like a less tragic version of Pale Fire. Now I'm one of those people who thinks that a lie becomes funny if it's ridiculous enough and told with a straight enough face. So the show appealed to me, but it's definitely not for everyone. If the squid narration above didn't make you laugh, you should probably steer clear. There's not that much to learn about editing, cinematography, or structure from Fishing With John. And as I noted, it's not even a movie. So what's it doing in the Criterion Collection? My theory is this: If I'd seen this show on television, I would work my ass off to see that it was released on DVD, because no one I described it to would believe that it actually existed. So file this one under one of the less obvious goals of a DVD library: preserving the unbelievably odd.

Randoms:

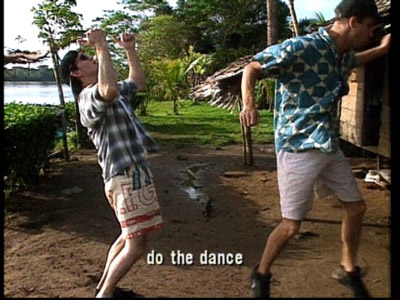

- The guests are willing to play along with John's craziness to varying degrees. Tom Waits came up with the idea of putting a fish down his pants, but over the course of the episode, seasickness and poor planning put him into a foul mood; after the episode, he and John didn't speak for several years. Matt Dillon, on the other hand, barely spoke while on the show. John hadn't wanted him as a guest, but the producers insisted. The episode revolves around John and Matt being taught a Costa Rican fisherman's dance to increase their luck. Matt, afraid of looking ridiculous, was only willing to dance around with John for a very short time, so this sequence rather obviously features the reuse of the same few seconds of footage again and again. Throughout the rest of the episode, Matt is extremely unwilling to talk, apparently for fear of being made to look foolish. Well, that won't do. So here, preserved for posterity, is Matt Dillon dancing around like a fool in Costa Rica:

- In the Tom Waits episode, Lurie had problems finding a boat large enough to film on (it has to be large enough to rock gently). There weren't any, so he bought an unseaworthy tugboat and had it fixed at great expense; its anchor, for example, was flown to Jamaica from Miami. I don't even want to think about the costs of shipping an anchor. Lurie describes this as his Werner Herzog moment. Here's the boat, looking spectacularly unseaworthy.

- The boat was unbelievably rusty and cut both John and Tom's shins to ribbons, which no doubt had something to do with Tom's terrible mood.

- Although the show often gives the impression that John and his guest are fishing alone, the camera crew is always there, and sometimes very poorly concealed. For example, what's wrong with this still?

- If you answered "The camera guy hiding under a blue blanket," you're right. Here he is again:

- If you do think straight-faced lies are funny, I highly recommend The Haggis-On-Whey World of Unbelievable Brilliance, a series of beautifully designed, lavishly illustrated children's books that contain not a single actual fact. Giraffes? Giraffes! is a personal favorite. Did you know that giraffes arrived on this planet on a conveyor belt from Neptune?

- The cinematography isn't much when compared to film, and a lot of it is mediocre looking, but in a few places, it's beautiful. Here are two stills, both from the Thailand episodes:

- Looking at these locations, I can only conclude that I should start my own fishing show as soon as possible.