Armageddon, 1998, directed by Michael Bay, screenplay by Jonathan Hensleigh and J. J. Abrams, adaptation by Tony Gilroy and Shane Salerno, story by Robert Roy Pool and Jonathan Hensleigh (I have no idea what work those writing credits actually correspond to).

Armageddon seems like an odd choice for a Criterion edition, but if the collection is intended to provide a representative sample of film throughout history, neglecting the late-90's studio system would be silly. If you're one of the three people who didn't see it, it was pitched as "Red Adair in space," and later as "The Dirty Dozen in space." The basic story (and it is the most basic of stories) is that a gigantic asteroid is on a collision course with earth, and NASA sends a group of twelve oil-drillers into space to plant a nuclear bomb that will destroy the asteroid and save the planet. Here they are in full The Right Stuff-hero-mode (which is the only mode they've got):

Armageddon exemplifies a certain type of movie; the big, dumb, loud, critic-proof summer blockbuster. This sort of disaster movie is still around, but it's evolved a lot in the last seven years. The closest thing to Armageddon this summer was War of the Worlds, which is a much more thoughtful movie. Here's why:

New York, post meteor shower.

The destruction of American cities is no longer a guilt-free pleasure. There's a reason that The Onion namechecked producer Jerry Bruckheimer when they wrote this, and Armageddon is his masterpiece. Watching it now, you see so many scenes that simply could not be made today, or even conceived of, and for me that made rewatching it oddly poignant. The men and women who worked on the film were certain that they were living at the end of history. Too bad it didn't work out that way.

Critics who thought Armageddon was a sort of terminal end point for filmmaking (which is to say, all of them except David Edelstein, as far as I can tell) missed the point. Janet Maslin, for example, wrote, "Armageddon tries to tell a coherent story of guts, young love and space travel." But I don't think it does try; it's not really interested. You wouldn't criticize Star Tours or Batman: The Ride for shoddy characterization or wooden acting, and it doesn't seem fair to me to treat movies like Armageddon as though their writers and directors had the same goals as, say, Tarkovsky. David Foster Wallace put it best (in "David Lynch Keeps His Head"):Art film is essentially teleological; it tries in various ways to "wake the audience up" or render us more "conscious." (This kind of agenda can easily degenerate into pretentiousness and self-righteousness and condescending horsetwaddle, but the agenda itself is large-hearted and fine.) Commercial film doesn't seem like it cares much about the audience's instruction or enlightenment. Commercial film's goal is to "entertain," which usually means enabling various fantasies that allow the moviegoer to pretend he's somebody else and that life is somehow bigger and more coherent and more compelling and attractive and in general just way more entertaining than a moviegoer's life really is. You could say that a commercial movie doesn't try to wake people up but rather to make their sleep so comfortable and their dreams so pleasant that they will fork over money to experience it – the fantasy-for-money transaction is a commercial movie's basic point. An art film's point is usually more intellectual or aesthetic, and you usually have to do some interpretative work to get it, so that when you pay to see an art film you're actually paying to work (whereas the only work you have to do w/r/t most commercial film is whatever work you did to afford the price of the ticket).

Some movies blur those distinctions (all of the studio products so far in the Criterion Collection, for example), but Armageddon may be the most commercial film ever made. And I mean that in every sense of the word commercial; Roger Ebert called it "the first 150-minute trailer." Michael Bay and his cinematographer John Schwartzman made the jump from advertising to features, and they brought that sensibility with them. What you get is perfect framing, beautiful photography, but what's actually on-screen is pure wish-fulfillment in a way that's completely divorced from narrative. Like this:

That's the end shot of a love scene between Ben Affleck and Liv Tyler. It's lovely, but it doesn't have any basis whatsoever in reality. Where is the house they've driven to? Does it belong to either character? Why have they strung Christmas lights in the tree? When did they do this? Are we really meant to believe that A.J., a roughneck who works on oil rigs, drives a cute little BMW Z3 when he's on dry land? You can take nearly any frame in this movie and pick it apart in this way, but that presupposes that the goal of this film is to tell a story, and I don't think that's true. The story is a vehicle for the wish-fulfilment you're paying for; when it's in the way, it's jettisoned. This shot does exactly what it sets out to in terms of the mood it evokes in the viewer. It's not a subtle emotion, it's not a subtle shot, and it's not a "justified" shot in any way, shape, or form. But as fantasy, it's great; it's the world advertising has always promised us. (And, of course, it is advertising: BMW paid a good deal of money to have A.J. drive such an unlikely car).

The point is, that shot succeeds brilliantly at "enabling various fantasies that allow the moviegoer to pretend he's somebody else and that life is somehow bigger and more coherent and more compelling and attractive and in general just way more entertaining." So does the rest of the movie. Seen from those terms, all the laughably absurd plot points and continuity errors in the world don't really matter. So the movie takes place in a world without time zones, in which it's simultaneously daylight in India, New York, and Paris; so what? You think Bruce Willis has time to keep track of time zones when humanity's future is at stake? Here's a single tear for narrative coherence:

Now if you'll excuse me, I've got a planet to save.

There's another reason Armageddon specifically belongs in a collection like this one: thanks to Top Gun, Jerry Bruckheimer was able to get the crew unbelievable access to NASA facilities during the filming of this movie. So there are shots and sequences that are completely unprecedented, and sheer techno-pornography for someone who, like me, grew up in love with the space program. (Let me put it this way: at age 6, I had a record of radio highlights from the first Columbia launch). Except for mission control, most of the NASA facilities you see in the movie are the real thing, from the vacuum chambers to the shuttle assembly building to the neutral buoyancy pool. Ben Affleck and Bruce Willis became (and remain) the only two civillians to ever wear real space suits for the underwater sequences. This shot isn't faked or altered in any way; that's the cast of the movie on the real gantries with the real shuttle, a few days before a real launch:

And could there be anything hotter than making out in one of the rocket exhaust cones of the Saturn V booster?

Of course, my own weird space-nerd childhood doesn't really have a bearing on the movie for most people. But it is valuable to see an example of the sort of filmmaking excesses that can result when a filmmaker is allowed to have anything he wants. For example, there's a scene where William Fichtner briefs the crew. In the real world, this would probably happen in a briefing room. Michael Bay decided he wanted it to happen in the shuttle assembly building with a B-2 and 2 SR-71 Blackbirds. So the Air Force flew in the planes, asked him where to park them, and this is the result:

You can't see the B-2 in this shot because it's parked over to the left. It had to be there, because both the engine exhaust and the trailing edge of the wing were classified at the time and could not be photographed. When you see the movie notice that the tail end of the plane is always out of frame. In fact, the crew wasn't allowed to see the back end of the plane at all. Which is to say that Jerry Bruckheimer is able to get the Air Force to risk national security to indulge his director's whims. That sort of excess is unparalleled in film history. And it actually doesn't make me too happy with the Air Force, because, after all, I paid for part of the production of Armageddon, as did most of you. Without any back-end participation at all.

The level of personal wish fulfilment in Armageddon is pretty easy to pick out; it's worth noting that Michael Bay also sells a kind of national wish fulfilment. Armageddon has a serious hard-on for the early days of the space program, specifically for the sense of national purpose it gave the country. In fact, the movie suggests that that America, that national conception of ourselves, is still pretty much what we are, as you can see below. Show these four frames to someone who doesn't know what they're from and ask them what year each one depicts:

My guess is nobody says 1998 for any of them. Note the NASA hero-worship in the third frame; here's a close-up of one of the soapbox derby cars:

When's the last time you saw a kid with a helmet like that, much less a soapbox derby car? The more observant among you will have also noticed that the last still quotes this photograph from Robert Frank's The Americans:

That photo was taken in the early fifties, before Sputnik, and definitely falls under "American mythmaking" (put it this way, Jack Kerouac wrote the introduction to the collection). None of the above is subtle, but here's maybe the most blantantly manipulative shot in the film:

In case you miss it, this shot is immediately followed by one of the astronauts saying "Kennedy, we see you. And you never looked so good!" Of course, he's talking about the Kennedy Space Center...or is he? The point is, these sections are shamelessly manipulative and there's nothing delicate about them. Nevertheless, they have an elegiac tone that's more moving than anything else in the movie. And they seem motivated by a genuine longing for a national purpose, and national heroes, for a more innocent version of America. Of course, that America never really existed, and Armageddon offers Bruce Willis as just the sort of national hero we're looking for, but hey, you take your pleasures where you find them. If you're willing to let go of outdated values like "coherence" and "narrative," you'll find plenty to love in Armageddon.

Randoms:

- If you want to piss off a DP, make him shoot space helmets that expose the whole face. There's nowhere to hide a light (notice how much of the face is covered in the helmets in movies like Alien), which means you have to light them from outside the helmet, which means reflections. John Schwartzman eventually came up with the solution of sticking a light on top of every helmet, so that when you saw reflections of lights in every shot, you would at least think they were coming from another astronaut's headlight and not from a film crew. Here are the helmets:

- Disney's marketing campaign for Armageddon is a story in and of itself. A few highlights:

- 50 minutes of the film was shown at Cannes to laughs and catcalls. After the screening, Bruce Willis gave the most hostile press conference of his career, berating the assembled foreign journalists for their reaction to the movie.

- This was the second asteroid movie that summer; the first was Deep Impact. Disney thought its only real competition was Godzilla, however, and that's why there's an early scene of a toy dog mauling a Godzilla doll (N.B.: those scenes feature a dog that had been specifically trained to attack Godzilla dolls!).

- Commercials for the movie, including the Superbowl spot, are included on the disc. I thought it was incredible how primitive they seemed compared to ads for movies right now. But I suppose they seemed primitive at the time, too.

- 50 minutes of the film was shown at Cannes to laughs and catcalls. After the screening, Bruce Willis gave the most hostile press conference of his career, berating the assembled foreign journalists for their reaction to the movie.

- This is a more religious movie than any other action film I can think of. Characters are continually invoking God and praying. Like the shots of a non-existant small-town America, this is described on the commentary track as an entirely cynical ploy to attract people from flyover country. Given the amount of contempt most studios have for the intelligence of moviegoers in red states, it's strange to me that this particular cynical ploy isn't used more often. If you have any doubt about Hollywood studio executives' feelings about the middle of the country, let me put it this way: a few months ago I saw a memo from a well-respected producer to a well-respected studio executive in which he argued that a director who both men thought was out-of-touch and past his prime would be perfect for a particular project, because only someone out-of-touch could make a movie simple enough for moviegoers in the middle of the country to relate to. This is not, by a long shot, the worst example of this sort of thing, and if I ran a studio it'd be the first thing I'd ban; if executives made movies they actually wanted to see, I think the world would be a better place. Note also that when I say "studio executives," that's who I mean, not filmmakers and not some nebulous idea of "liberal Hollywood."

- Watch for a nice cameo by Udo Kier, star of Blood for Dracula and Flesh for Frankenstein. He plays the psychologist who has to analyze the astronauts to be. For reasons only he can explain, Michael Bay chose to set these scenes in a parody of a soundproof room with spiked walls:

-

It's-a me! Dracula!

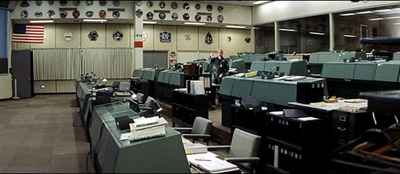

- Armageddon does cheat on at least one NASA location; Mission Control. Here's the film's version:

- And here's the real thing, also in the film:

- You can't make him out, but that's Owen "Butterscotch Stallion" Wilson goofing around in the old mission control. Despite looking like a community college classroom, that's where they ran the moon landings.

- There are some excellent features about the special effects. The most surprising is this shot of the destruction of Paris:

- I always assume shots like this are completely CGI (and today they probably would be), but in fact only the overlay of the Paris streets below is CGI. The gargoyles are a real shot, and the blast circle approaching camera was made by photographing a real explosion of nearly 50 concentric circles of explosive buried several feet under dirt.

- Although Robert Towne supposedly did some polish work on this script, Steve Buscemi contracts "space dementia" at a certain point in this movie, for no apparent reason, and with no real consequences. I just thought that should be clear at the outset if you're planning on watching it for the quality of the writing.

- There's an entire commentary track with the "science advisors," a NASA employee and a former astronaut, who tried to make the movie as scientifically accurate as possible. Listening to these guys talk about their constant battles to get Michael Bay and company to make the film at all relate to the world of science (for example, when Mir explodes, it explodes, like it's in an atmosphere) is a case study in cognitive dissonance.

- The Armadillo, the drill car they drive around on the asteroid, has a chin mounted chain gun. You might wonder when NASA started putting weapons on their vehicles, or what they were expecting to shoot at on an asteroid, or even how they expected bullets to fire in a vacuum. But in fact, this wasn't NASA's decision so much as Mattel's; there was a toy version of this car, and toys with guns sell better. I'm not kidding; plot points were decided on by the toy company.

- Manny Perry, the guy who was the MPAA's copyright spokesman for a few glorious months, did some of the stunts in this. I can't begin to tell you how delighted I was to see his name in the credits.

- Like I said, the NASA sets were mostly real. Ben Affleck's teeth? Not so much. And I wouldn't put money on Tom Cruise's. Here's Michael Bay talking about working with Affleck on the commentary track:

I had him work out. We paid for a set of twenty thousand dollars of pearly white teeth—Ben's gonna hate that story—uh, I always like low shots that kinda come right under your chin, just make you a little bit heroic, and he kinda had these baby teeth. So, uh, I told Jerry Bruckheimer, I said, "God, he's got these baby teeth, Jerry, I don't know what to do." Jerry used a very famous star in a... plane movie that he replaced teeth with so, uh, he says, "We did it to him, why not do it to Ben?" So my dentist had Ben sitting in a dentist's chair for a week, eight hours a day.

- If you develop over 1,000,000 feet of Kodak film on a single production, Kodak sends you a gift basket with six bottles of Korbel. Michael Bay complains on the commentary that they could have sent two bottles of Dom Perignon for the same money. So, Kodak, if you haven't sent out those gift baskets for The Island yet, take note.

Armageddon was a nice break from my self-planned crash course in foreign and art house film. Now it's back to movies with a little more on their mind. At least until I get to The Rock.