Mona Lisa, 1986, directed by Neil Jordan, screenplay by Neil Jordan and David Leland.

As anyone who has ever been a teenager will tell you, romantic obsession is more about subject than object. Proust grasped this completely:

No doubt very few people understand the purely subjective nature of the phenomenon that we call love, or how it creates, so to speak, a supplementary person, distinct from the person whom the world knows by the same name, a person most of whose constituent elements are derived from ourselves.

When you name your film after the blankest canvas in Western art, it's clear you're going to be exploring some of the same territory. Whatever Lisa del Giocondo may have been like in person, she is now and forever the sum of all the supplementary persons other people have projected onto her. Opening with Nat King Cole's song ("Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa, men have named you...") is the icing on the cake. But out of all of the six million people who see the painting each year, geniuses and not-so-geniuses, only Neil Jordan looked at that mysterious smile and imagined Bob Hoskins smashing a pimp's face to a bloody pulp through a car window.

Mona Lisa is the strangest of films: a study of "the vast gulf of misunderstanding between men and women," wrapped in a fairy tale, wrapped in a Pygmalion story, wrapped in a British gangster movie. Oh, and tied up with a bow stolen from Taxi Driver:

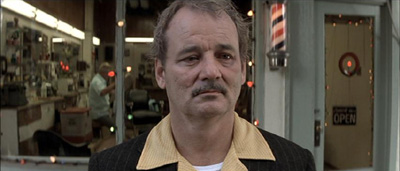

Nothing about that combination should work, but it does, and wonderfully. It's the actors that put it over, mostly because they're so perfectly cast. The main character is the kind of part Bob Hoskins tears to shreds: a Little Englander named George who has just been released from prison. Hoskins can tell you so much about his character through the smallest gestures: look how much exposition he spares us with the expression on his face upon seeing blacks in his old neighborhood:

His ex-wife won't see him, his daughter doesn't know him, the criminals he did time for have abandoned him, and his neighborhood has collapsed. The one person who's glad to see him is his friend Thomas, played by Robbie Coltrane.

And here's where things start to go off into fairy tale land. Coltrane looks like a Hobbit to begin with, but Jordan has him live in the closest thing British gangster films have to an enchanted cave: a broken-down RV marooned inside of a garage.

If the look of the garage (or Coltrane, for that matter) didn't tip you off that this is a strange, magical kind of a place, perhaps the artificial plates of spaghetti are a clue:

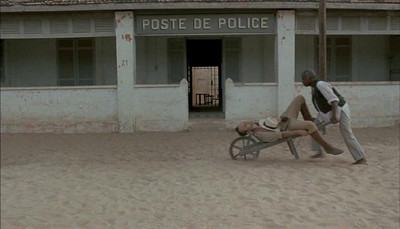

It all seems a little on the nose laid out like that, but the great thing about Mona Lisa is that it's hard to think of it as anything but a straightforward British gangster film while watching it. How much British gangster credibility does it have? This much:

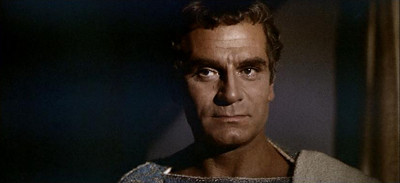

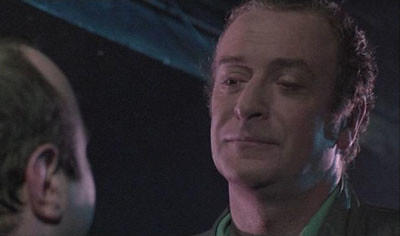

I love The Long Good Friday, but Michael Caine's Mortwell trumps Eddie Constantine any day of the week. Although George has been out of the picture too long to be of much use to his old crew, Mortwell throws him a bone: a job driving a high-end call girl named Simone from one assignation to another. Cathy Tyson plays Simone as the perfect embodiment of unattainable glamour and mystery.

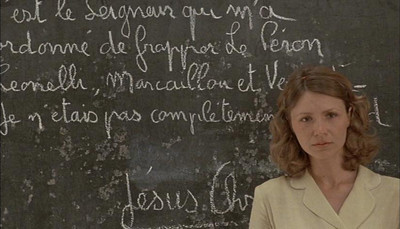

Cathy's inner life is completely unimaginable to George, and he can't help but fill in the blanks. As in The Crying Game, the gulf between George and Simone has as much to do with class as gender: Simone may be "a tall, thin, black tart," as George puts it, but she moves in circles where George never fit in. He doesn't even know how much he doesn't know. On ordering tea from a hotel lobby bar, the waiter asks him, "Earl Grey or lapsang souchong?" "No, tea," George growls, unsure whether he's being made fun of. When Simone gives him money to buy better clothes, he shows up looking like this:

This leads to some of the film's funniest scenes, as Simone remakes George in a sort of reverse-Pretty-Woman sequence.

And that's where the troubles begin. People always forget that Henry Higgins took Eliza Dolittle under his wing to win a bet; Pygmalion sold a whole lot of statues before he fell for one of them. But really, how could George do anything but fall in love with the woman who makes him feel like he's as good as anyone else?

Simone isn't as innocent as a 16th-century sheet of poplar, of course. She's complicit in George's fantasies about her, because she wants more from George than the minimal social graces she'd require from a driver. She's desperately trying to find a prostitute named Cathy she knew when she was working a considerably more downscale beat, before life on the streets kills her. Night after night she has George drive her around neighborhoods as hallucinogenic as anything in Taxi Driver.

When Scorsese lights the streets that dramatically, it's because we're seeing them through the eyes of a man who imagines his alienation to be romantic, but whatever pale fire lights this shot in Mona Lisa is stolen from Simone. This becomes abundantly clear when George goes looking on his own, through a series of steadily more depressing clip joints. The sequence is horrifying enough that producer Denis O'Brien only allowed it in the film on the condition that it was a montage (set to "In Too Deep," by Phil Collins, which I'm sure the clubs' patrons would agree is an epic meditation on intangibility). The lighting is never flattering.

Things reach their inevitable nadir when George, believing he's finally found Cathy, is ushered into a sad little bedroom where a fifteen-year-old girl (Sammi Davis) sets aside her teddy bear and insists that she "make him happy."

She reminded me of Nabokov's sallow girl with her bald doll, a travesty of familial feeling. She's not really Cathy, it's not really her bedroom, and George can't save her. He does eventually find the woman Simone is looking for, in a church, of all places. And then things start getting really nasty.

Nearly every scene is filled with the detritus of fairy tales gone sour: pink frills, ice cream, "Michael Finnegan." George steals Cathy away from her rapist by vanishing her through a one-way mirror that opens like a door. When Simone tells George the story of her escape from low-end prostitution, it feels like the details she elides could involve wicked stepmothers, princes in disguise: "I met a man with a gold ring who took me to Brighton. When I woke up, he was gone." The whole thing sounds absurd on the page, and yet it feels so grounded in a particular time and place I never questioned the reality of the characters and their situation. Neil Jordan slips up only once, in my estimation, by staging Cathy and Simone's reunion at a roadside restaurant that makes the fairy tale aspects of the story too explicit. You might say he clobbers the audience over the head with a gigantic shoe.

It's the only misstep in a film that otherwise blends fairy tale archetypes and the seedy particulars of London crime with absolute virtuosity. I can't imagine any other director mixing the ridiculous and sublime as boldly as Jordan does when he has Bob Hoskins, at his moment of greatest fury and hostility, wear novelty sunglasses.

A little context is necessary: Hoskins is playing at being on vacation at the beach. It's thematically linked with all the other points in the film where characters do a bad job of pretending to have a good time. So it's brave, but it isn't entirely crazy. But have that same scene collapse in on itself and show us Simone and George at their rawest and most vulnerable, while still wearing those goddamned glasses: that's brilliant.

"You ever need someone?" Simone asks, and what she means, in this film about misunderstandings, is "Do you understand me?" George swallows, and looks at her, and the pause before he answers and the way Hoskins makes his voice crack when he finally speaks broke my heart. George says what he says, and you can tell it's as honest as this sad, lonely man has ever been with himself, and then he walks a little distance away to lean against the boardwalk's awning. He can't stand to be close to her at that moment, but he's near enough that she could follow. We know he hopes she does. "You ever need someone?" she asks him. "All the time."

Randoms

- Simone's vicious ex-pimp is played by none other than Clarke Peters, who went on to play Lester Freamon on The Wire. He's considerably less avuncular here.

- Peters is also quite an athlete; he makes a flying leap over the corner of a pool table that I'm sure would end with a broken nose were I to attempt it.

- Mona Lisa was produced by HandMade Films, a collaboration between Denis O'Brien and George Harrison (they also made Monty Python's Life of Brian). I already mentioned that O'Brien was responsible for the Phil Collins montage, but Harrison contributed as well. According to Neil Jordan, his one stipulation was, "I just don't want to see any naked dicks in this movie." There are no naked dicks in Mona Lisa.

- This is the first non-anamorphic widescreen DVD in the collection in a long time; it's overdue for a new transfer. Although if any movie is going to benefit from looking grainy, it's a gangster movie set in and around strip clubs.

- Bob Hoskins tells an amazing story about Michael Caine on the commentary track that's too great not to reproduce in its entirety:

I met Michael in Mexico. I was doing a film in Mexico with him. [Presumably Beyond the Limit] The first time I ever met Michael, he got ahold of me, he said, "''Ere. C'mere. I wanna talk to you." He says, "You've got a lot of talent and you're gonna earn a lot of money. And there's fings you do with your money and there's fings you don't do with your money, and the first fing you don't do with your money is buy a fucking boat, right?" Every time I see him: "I ain't bought a boat, Michael, I promise you." "Buy a house. That's better."