Do The Right Thing, 1989, written and directed by Spike Lee.

It's hard to believe it now, but on its initial release, Do The Right Thing caused a genuine public

uproar. Critics wrote that Spike Lee's film would inflame racial hatred, incite riots, and, perhaps worst of all,

doom the mayoral campaign of David Dinkins. Actually, the only person who made that last claim was Joe Klein, who

in a truly remarkable column

for New York magazine, asked the question that was on no one's mind but Joe Klein's: should David Dinkins

be held responsible for Spike Lee's movie (and Public Enemy's music)?1

Klein's response may have been particularly egregious, but other critics weren't exactly models of restraint.

Richard Corliss wrote that Lee's aim was to "create a riot[...] of opinion[!]" (ellipsis and exclamation mark mine, but they certainly improve

the sentence). Stanley Crouch called Lee an "Afro-Fascist," whatever that means. David Denby worried that black audiences might "go

wild" after watching the film. Even critics who loved Do The Right Thing (e.g., Roger Ebert)

spent time and ink discussing whether or not it would incite racial violence.2

This is probably a good place to note that, to this very day, no one has written a review of Field

of Dreams wringing their hands about whether or not it would incite kidnappings of J.D. Salinger.3

Okay, maybe that isn't quite fair. For one thing, it wasn't all that crazy to think that riots were on the way, though blaming Spike Lee instead of centuries

of institutionalized racism seems a little convenient.4 Still, it's not like

Do The Right Thing was the first movie to suggest that maybe America had a bit of a race problem—so

what was it about this film in particular that provoked such a firestorm?

Maybe a little context on the state of race in mainstream American movies around the time Do The Right

Thing hit theaters will help. In 1989, the year Do The Right Thing was released, Mississippi

Burning was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Glory had fewer nominations,

but actually won three awards. In 1990, Driving Miss Daisy got nine nominations and won Best Picture.

The year after that was Dances With Wolves, which I guess at least leaves African-Americans out of it.

The moral is clear: in the late eighties, if you wanted to make a successful and critically acclaimed movie about

race in America, there were a few rules you had to follow:

- Make your main characters white. You may remember Denzel Washington or Morgan Freeman as main characters

in Glory, but you're wrong: it was Matthew Broderick.

- Spend as little time as possible with non-white characters outside of their interactions with your white

protagonists. Think of Driving Miss Daisy: What did Hoke do on his day off?

- Always, always remember: racism was a historical phenomenon, largely confined to the South, overcome many

years ago by heroic white people on behalf of grateful African-Americans.

Thank God Spike Lee wasn't paying any attention. It would be easy to imagine a version of Do The Right

Thing that followed the traditional Hollywood template, but such a film would almost certainly be a "hackneyed melodrama [that] doesn't demand

imaginative self-examination."5 Demanding imaginative self-examination is a

pretty high standard to hold a film to, and there are good, and even great films that don't meet it. And I'm not angling for a long discussion of the relative merits of the other films I mentioned. I just want to provide a little context: it's an achievement in

itself to get Universal to release a film about race in America in which, search though you may, you will not find

a single magical negro.6

What you will find instead is a film school geek's dream movie: Lee, cinematographer Ernst Dickerson, and set designer

Wynn Thomas fluidly draw from all sorts of precedents, most of which can be filed under "things Martin Scorsese

likes." I realize that's a broad category, but when you're coloring things like Jack Cardiff and paying

homage to Robert Mitchum in Night of the Hunter, I think it's justified.

Still, the most obvious influence on the film one you don't find much in Scorsese: theater. Do The Right

Thing is the rare film that observes the classical unities, chronicling 24 hours on a single block in

Bedford-Stuyvesant. Lee shot almost entirely on location, but his version of Bed-Stuy owes more to Depression-era

theater than it does to Brooklyn. In fact, the first time we see the neighborhood, it's as a tinted backdrop

hanging behind Rosie Perez.

Backdrops are commonplace on stage, but to find a film with that kind of frank artifice, you'd have to look at

MGM musicals. Which, if I remember correctly, rarely featured furious Puerto Ricans in boxing gloves.7

And once we get to location shooting, Do The Right Thing still looks and feels more like a play than a

movie. The picture below is a real window in a real building in Brooklyn, but the framing makes it look like part

of the set for an above-average production of Street

Scene. Having Ruby Dee sitting in the window is

something of a tell.

Dickerson and Thomas freely manipulated real locations for visual effect, without too much regard to

verisimilitude. Good luck finding a wall this color in a real city.

That's Paul Benjamin, Robin Harris, and Frankie Faison as the second closest thing the movie's got to a Greek

chorus: three good-for-nothings for whom crossing the street to get a beer is a major ordeal. The closest thing to

a chorus is the film's narrator, one Mister Señor Love Daddy, a DJ blessed with the voice of one Samuel L.

Jackson.

So, yeah, Spike Lee's Bed-Stuy doesn't feel like a neighborhood you could actually go visit, not least because

it owes nothing to the gritty way most people shoot anything to do with urban poverty. The audience's guide is, fittingly enough,

Spike Lee himself, as an irresponsible, money-obsessed pizza delivery man named Mookie.

He's employed by Sal's Famous Pizzeria, run by Sal himself, a genial Italian played by Danny Aiello. Sal is

assisted by his two sons: the frankly racist Pino, who John Turturro portrayed convincingly enough that one of the

craft services women thought he was sincere:

And his younger brother Vito (Richard Edson), who is friendly enough, but lets his brother steamroll him. Here

he is clowning around with Mookie in the WE-LOVE studio.

The one classical unity I haven't discussed is unity of action, but rest assured, Do The Right Thing

observes it. In this case, the action that is "complete,

whole, and of a certain magnitude" is an incident of police brutality and the riot it incites. The flashpoint

for the block's troubles is an excitable would-be activist named Buggin' Out. The first time we see Buggin' Out unhappy,

he's complaining about the lack of cheese on his slice of pizza:

Sal is about as sympathetic as you'd expect any pizzeria owner to be when accused of culinary malpractice. So

we're meant to question Buggin' Out's sincerity when he immediately picks a fight with Sal over the lack of

African-American faces on Sal's all-Italian "Wall of Fame."

Angry at Sal's response (basically: start your own pizzeria and put whoever you want on the wall), Buggin' Out

tries to rally the neighborhood to boycott Sal's. He convinces exactly one person: Radio Raheem. Bill Nunn plays

Raheem as The Sum Of All White Fears, a giant who prowls the neighborhood blasting Public Enemy from an honest-to-

god boombox.

In one of the film's most audacious scenes, Lee has Raheem perform Robert Mitchum's monologue from Night of the Hunter. Mitchum's version has maybe the highest

menace-per-frame rating of anything in cinema. But even though Lee has Raheem deliver the monologue straight into

the camera, even though Raheem delivers shadow punches right at the viewer, even though he changes Mitchum's

tattoos into brass knuckles, Raheem's version is the opposite of menacing: it convinces you he's basically

harmless.

Mookie's response is a more or less baffled, "There it is. Love and hate." Then he heads off to deliver a

pizza.

Nobody remembers Do The Right Thing for defanging Robert Mitchum, though, and it's a measure of the

filmmakers' skill that they can go from a scene like that to a climax where violent conflict seems inevitable.

You could write an entire essay about the thematic and structural ways Lee stacks the deck... and many people

have. But I think part of the reason critics felt so strongly about Do The Right Thing is just how

effectively Lee makes the audience feel just as angry, stressed out, and ready to blow as his characters, and it's

not all about theme or plot. So instead I'd like to talk about some of the purely cinematic techniques that are

used to slowly ratchet up the tension.

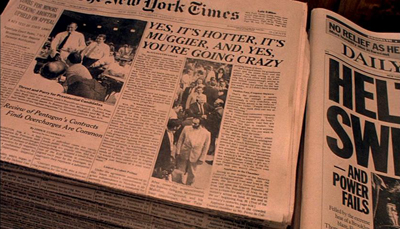

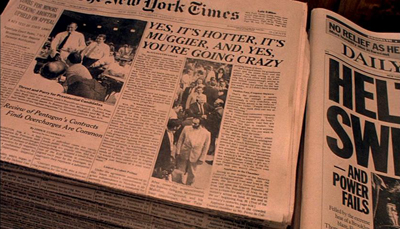

The first is more of a problem than a technique: Do The Right Thing takes place on the hottest day of

summer. As someone who's spent summers in Durham, North Carolina without air conditioning, I don't have to look at

crime rate statistics to tell you that extreme heat frays nerves as efficiently as air raid sirens. Getting that on film is a problem, however, because temperature is right up there with taste and smell: you can't film it. Most filmmakers resort to stock footage of a weatherman,

and Lee certainly isn't above getting that explicit.

But look again at the stills I've posted so far, and find me one with a cool color. If Jason Salavon ever does a piece about Do The Right

Thing, it will be a block of solid red. Every frame swelters: Lee and Dickerson even put lit cans of sterno

just out of sight in front of the lens to give some shots a visible heat shimmer. Even when we see characters

cooling off, the color scheme favors red:

There's exactly one shot that is legitimately cool, and it's carefully placed.

That's Ossie Davis as Da Mayor. This shot takes place shortly after Da Mayor has saved a kid from getting run

over by a car. It's right as the sun goes down—we see the street light come on—and Da Mayor, the least

confrontational character in the film, is telling a story about a long ago triumph (scoring the winning run in a

baseball game). There is a moment on even the hottest of days, when the sun's vanishing makes it seem cooler than it

actually is. Where did Da Mayor score this run? Snow Hill, Alabama. That's pretty sly of Lee: despite the name,

I am guessing Snow Hill is not great country for skiing. And although this is the last time we'll see cool colors

in the film, this isn't the last time Lee will conjure up Alabama.

The next thing I think Lee and Dickerson are up to, I'm not as certain about, not being a cinematographer. It

appears to me, however, that they have made a concerted effort to flatten perspective throughout the film, and

that's one of the things that makes the block seem increasingly claustrophobic. Take a look at this dolly zoom

as Radio Raheem enters Sal's; the shot starts here:

By the time Raheem has reached the door, it looks like this:

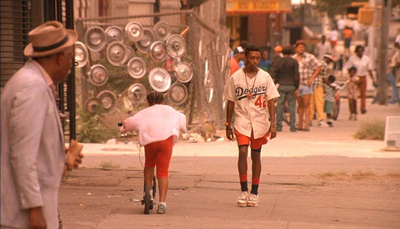

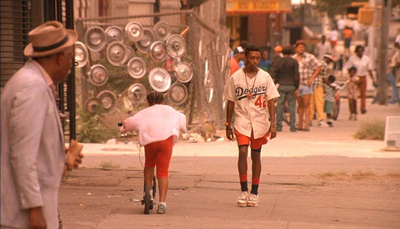

It's like the street is narrowing as we watch. Consider also the lengthy shot of Mookie walking down the street

toward the camera. Lee and Dickerson use a zoom lens, keeping Mookie in roughly the same part of the frame without

moving the camera.

Between those two shots, Mookie has walked at least half a block towards the camera, but he isn't any closer.

Furthermore, there's no suggestion of movement, the way there would be if they'd dollied back with him (or used a

steadicam). Nobody's going

anywhere.

Another technique at play here is the sound. I can't illustrate this with stills, but let me assure you that this is one of the loudest

films I have ever heard, from Public Enemy blaring at the beginning to the final catastrophe. I don't mean that I

had the volume up too loud (though my neighbors would probably disagree); I'm talking about relative sound levels.

In most films with angry crowds, the sound mix has sort of a background rumble, with the dialogue of the most

important people foregrounded: in Do The Right Thing, it's all foreground. I've certainly seen films with

more people screaming at each other than in the final scenes in Sal's Pizzeria, but I can't any of them staging as

brutal an assault on my ears as Do The Right Thing. That's not a criticism; when Sal finally snaps and

bashes in Raheem's boom box with his baseball bat, it's crucial that the audience know why he's doing it.

The sound department rarely gets to explain themselves on DVD commentary tracks, but I would be very interested

to hear more about how the film was mixed, because most films are not designed to make the audience want to

puncture their own eardrums.

The last thing Lee does is easily the most noticeable and easiest to imitate: he uses nearly as many head-on

shots as Ozu, but for very

different purposes. At least early in the movie, we often see conversations from one of the speaker's point of

view. I mentioned Radio Raheem's Night of the Hunter monologue, but I didn't mention that we're seeing

that monologue through Mookie's eyes. Lee establishes this with a technique I hadn't noticed before: a tracking

shot in which the camera sort of merges with Mookie's position from the side. You can see the same technique in

this shot, where Buggin' Out tries to recruit the neighborhood layabouts for his strike. The shot starts with the

Buggin' Out walking across frame from right to left, toward the camera:

He then has the camera pick up his motion and overtake him, so Buggin' Out disappears to the right of the frame

as the camera moves into the same path he was walking:

At the same time, the camera pans left until we're in Buggin' Out's POV, approaching the wall:

Which means we see their conversation explicitly from his point of view, as he talks to each of the men in

turn.

It's a remarkably fluid way to establish a POV shot, and it allows Lee to have actors address the camera

directly without drawing attention to the way he's staging conversations (I think the way Ozu does it is basically

only of use if you're making an Ozu movie). And it allows Lee to cut to a shot of Buggin' Out that is way too

close to be from anyone's point of view without the viewer noticing:

Lee trains the viewer to think of these direct-at-the-camera shots as being POV shots, which makes it all the

more unnerving when he breaks this rule, dropping the narrative to have several of his characters direct long

strings of racial epithets at the camera. Each one of these shots begins with a really fast track-in close:

We're not seeing this from anyone's perspective but the camera's, which means it's directed at, well, us. Lest

we mistake this for Mookie and Pino yelling at each other, we hear from characters who hardly speak otherwise, from

the cop who will kill Raheem later in the day:

To the Korean shopkeeper whose limited English means he barely gets a line outside of this section.

Of course, even this is just prelude to the confrontation between Raheem and Sal, when Lee cuts back and forth

between Buggin' Out and Sal so they're both yelling right at the audience:

Lee does a magnificent job of slowly applying pressure, so that when things turn violent, it's almost a relief, and I think that's part of the reason so many critics were up in arms about the movie. Lee doesn't say anything about

institutionalized racism that would have been out of place on the editorial pages of the New York

Times8, and certainly the events of Do The Right Thing were not

beyond the realm of possibility.9 Lee's crime, it seems to me, was to make a film

where a perceptive viewer will identify to a disturbing degree with the anger felt by all of the characters, to

understand why Sal smashes Raheem's boombox and why Mookie throws the garbage can. It's an article of

faith in American discourse that racism is a solvable problem, an error of perception. It's also an article of

faith in American films that racism is an error the characters make, for which the viewers judge

them.10 But as Do The Right Thing forcibly reminds us, everyone has his reasons.

Randoms

- Lee makes one truly brilliant structural choice by having Mookie throw the garbage can. It's not like Mookie

is a hero: Lee goes to great lengths to establish him as kind of an asshole. He's overprotective of his sister,

ignores Tina, is uninvolved in his son's life, can't hold down a job, and in general gives us no reason to think

he's going to be the voice of reason. But we're so used to characters like Mookie being passive observers that

it's truly shocking when he throws the first stone.

- My favorite shot in the film, by rather a lot, is this beautiful image of Mookie kissing his goodbyes to Tina.

They're shot in extreme close-up, just lips, really, with the last rays of sunlight flickering through a rotary fan

in the window:

Then Mookie pulls back out of frame and we stay on Tina's face, overexposed by a strobe effect as the fan

blades keep spinning.

- The block Lee shot on was on Stuyvesant Avenue between Quincy and Lexington. The Korean store and the pizzeria were built for the film, but the houses are still there. And as Google Maps shows, the Mike Tyson mural hasn't entirely faded.

- Lee makes the point on the commentary and in some of the supplements that many critics wrote about the burning

of Sal's Famous Pizzeria ("one of the stupider, more self-destructive acts of violence I've ever witnessed," as Joe

Klein put it), while somehow forgetting to mention Radio Raheem's murder. It couldn't be that they mourn the loss

of white property more than the loss of black lives, could it?

- Do The Right Thing was apparently the first film Michelle and Barack Obama saw together. American history might be quite different if he'd insisted on seeing The Karate Kid Part III, which opened the same weekend.

1Klein's answer was, "No, of course not, but people will hold him responsible

anyway." He was as right about that as he was FISA: Dinkins won the election, as far as I know without giving any Sister-Souljah/Jeremiah Wright

speech about Spike Lee and Public Enemy. Klein's column is documented proof that concern trolling predates the

World Wide Web.

2The only critic who completely ignored very important issue of Spike-Lee's-

Responsibility-For-Social-Unrest-If-Black-People-See-His-Movie-And-Get-Mad-At-White-People was, not too

surprisingly, Armond White, who wrote what seems to be the only contemporary review that focuses exclusively on the

film itself.

3And now it's too late!

4Like the man said, "A dog, if you point at

something, will only look at your finger."

5From Armond White's review of Crash, which went home with a few Oscar

statues itself.

6Spike Lee's term, as Wikipedia informs me! Even better, his original phrase was apparently "super-

duper magical negro."

7I know, I know. But there

aren't any boxing gloves, and that's UA anyway.

8Although the Times of the period seems to pull back from obvious

conclusions in the name of appearing reasonable. See e.g., this, in which

the paper outlines damning evidence of systemic racism in the NYPD (including not just specific incidents, but

things like "allegations of blatant racism among officers of the 113th" or problems with "thousands of recent

recruits"), but hilariously concludes, "Those episodes don't add up to the "systemic racism" that some allege."

9Just ask Michael Stewart! Or Eleanor

Bumpurs! Or Michael

Griffith! Oh, wait.

10The ideal audience for To Kill A Mockingbird is, of course, Atticus

Finch.