Good Morning, 1959, directed by Yasujiro Ozu, written by Yasujiro Ozu and Kôgo Noda.

A day or two after I first saw Good Morning, I received an email from Ozu fan and Criterion Contraption reader Lewis Saul urging me to watch any of his other films before this one. Apparently, Good Morning isn't emblematic of his work, and he was afraid I would get the wrong impression about Ozu if I started with this one. Well, I got the email a day late. I still haven't seen Tokyo Story, or any other films Ozu directed, but I certainly get the impression the bulk of his work is quite different from Good Morning. At the very least, the film seems a bit out of synch with his reputation. Peter Bradshaw, in an appreciation for The Guardian, characterizes Ozu's work as "gentle quietism and transcendental simplicity." I suppose you could argue that Good Morning shares those qualities, as long as you find something gently quietistic or transcendentally simple about the film's opening and closing scene: a farting competition that ends in tragedy when a young boy craps his pants.

Still, you know you're in the hands of a master director from the first frame. Ozu captures all the details a lesser artist would have missed, down to the uncomfortable, shuffling walk.

So this is not, perhaps, Ozu's most transcendentally simple or gently quietistic work. It certainly had a lot more scatological humor than I was expecting. Which is strange, because it's shot in a style you might, in fact, describe as transcendentally simple. When I wrote about Seijun Suzuki (Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter), I said he'd developed his own cinematic grammar, which I'd never seen before. Ozu doesn't have a grammar tied to thematic elements, the way Suzuki does, but he does have strict rules for shooting, which seem to have little connection to what's going on onscreen.

The first thing you'll notice about Ozu's style in Good Morning is also the simplest: he never, never, never moves the camera. No dolly shots. No zooms. No tracking around the room. He'll cut to a different angle, but every shot is static. You can't illustrate this with a still, obviously, but it's pretty striking.

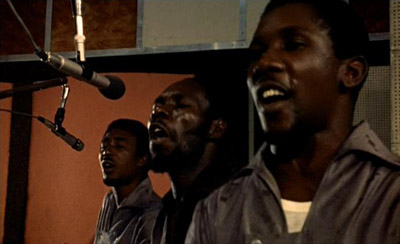

The second thing can be illustrated: Ozu often shoots conversations head on. Whether this violates the 180° rule depends on whether or not you think exactly 180° is permitted. For example, he shoots a conversation between Keiji Sada and Yoshiko Kuga by cutting from this:

To this:

I can say at the very least it's a little disorienting. Also note the slightly low angle, another Ozu trademark. Wikipedia refers to this as the "tatami shot," because the camera is placed at about the height one's head would be while kneeling on a tatami mat. Of course, to maintain that angle, Ozu had to get the camera even lower when he was shooting people who actually are kneeling on tatami mats.

Since Ozu didn't have to worry about a moving camera, each shot is very carefully composed. So Good Morning is full of lovely symmetries like this shot of Minoru and Isamu sulking:

Most people list those two kids (played by Koji Shitara and Masahiko Shimazu) as the film's main characters. I suppose that's fair: a major plot throughline involves those two deciding not to speak until their parents buy them a television. But that doesn't happen until nearly halfway through the movie. People remember Minoru and Isamu more than the rest of the film, because after a certain point, Ozu stays with them. It also doesn't hurt that Masahiko Shimazu appears to have been cast in the film after winning the Most Adorable Kid In The World Contest.

But the fact is, a lot of Good Morning isn't about them. The first half of the film follows a group of gossiping housewives trying to figure out what's happened to the dues they were supposed to pay to some neighborhood organization or other. There are enough subplots that it's hard to find a throughline that lends itself to plot summary. So although Minoru and Isamu's strike ties together a lot of the film's themes, I think it's more accurate to describe Good Morning as a portrait of a small Japanese community lurching towards modernity.

The structure of the film bears this up: it's a series of loosely connected comic vignettes, which may share characters and locations, but tend to have narratives of their own that resolve themselves independently of the rest of the film. My favorite of these sequences was not too surprising, given my predilection for con artists. Each of the houses is visited in the middle of the day by a door-to-door salesman, peddling overpriced household goods. When the women aren't interested, he sits down, casually, and urges them to at least buy a pencil. He pulls out a pocket knife and demonstrates how easy they are to sharpen, especially with such a sharp knife.

Not suprisingly, buying a pencil seems a lot more attractive as soon as the salesman pulls a knife. A few hours later, the same women are visited by a different salesman, a nice, much less threatening young man. He's selling alarm bells that can be used to summon the police in case of harrassment by pushy salesmen. Not surprisingly, everyone's interested. Later, we see the two men going over the day's take at a bar. The only household that's spared is the Haraguchis', where the grandmother insists on sharpening the pencil herself. With her own knife.

The salesman looses interest at that point. The grandmother is played by Eiko Miyoshi, and she's hilarious whenever she's onscreen. I also enjoyed Eijirô Tono's turn as a man forced into retirement too soon. His performance strikes just the right balance between sadness, anger, and alcoholism.

Tomizawa's retirement is the closest the film comes to getting serious. Ozu strings a few thematic concerns through most of the vignettes: anxiety about Westernization, lack of respect for the elderly, the way people use small talk to avoid saying what they're actually thinking, youth's sense of entitlement (though Asia hadn't seen anything yet), the forced intimacies between neighbors who would ordinarily loathe each other. It's obvious why problems with neighbors were particularly interesting in Japan of the late 50s: city planners seem to have been trying to duplicate the feel of the Tokyo subway at home:

There's a joke about rat poison towards the end that made me wonder if the movie was about to become pitch-black (it doesn't). The essays I've read about Good Morning make a great deal of hay out of the subtext; the thematic concerns I'm mentioned about. But since virtually every other scene has a fart joke in it, it's difficult to see this as some great statement about Japanese culture. Not that that's a bad thing—I'm ok with fart jokes.

I can't think of any other movie that looks quite like Good Morning(except, apparently, all the Ozu films I haven't seen). But as with Wes Anderson, the salient question is what the style is in service of. In the case of Good Morning, I think there's a disconnect between the style, which seems contemplative and a little sad, and the subject matter.

It's not that the film is without its wistful, thoughtful scenes, where Ozu's style seems appropriate. It's not a farce; it has its moments of languor. But the overall tone is wry, and the basic structure is that of a comedy of manners. I felt like the frozen camera was continually fighting with the subject matter and tone. Even in scenes that were charming and funny, there was something that seemed a little off about the whole endeavor.

It isn't entirely clear to me why some styles of filmmaking should suit particular genres. Obviously, some techniques can reliably produce particular results: cutting suddenly to a shot of the killer right behind the victim will always make an audience jump, point-of-view shots that don't appear to belong to any particular character give a sense of unease, and so on. Shock cuts are not a learned association, they tap into the startle reaction. But the link between point-of-view shots and unease could be learned, because most times you see that technique, a shock cut is just around the corner. I've never seen another film with as completely static a camera as Good Morning, but the closest things I've seen have all been dramas. I wonder if there's something about Ozu's style that is intrinsically better suited to drama than comedy, or if I could have associated Ozu-like camerawork with comedy if, say, Ghostbusters or Airplane! had been shot that way. But they weren't, and Good Morning didn't do much for me. I probably should have watched Tokyo Story first.

Randoms:

- Both Eiko Miyoshi and Eijirô Tono are stealth candidates for "most appearances in the Criterion Collection." She's in in countless Kurosawa films, plus two of the Samurai movies. He worked with Ozu and Kurosawa a lot (if I have this right, he is the kidnapper who staggers out and dies in the begining of Seven Samurai), and is also in two of the Samurai films.

- Ozu has a head-on shot of Isamu and Minoru watching television, a rarity in the pre-genlock days.

- As you can see, he avoided scan lines by cutting out the screen on the original image and pasting in a film image of the show they're supposedly watching. It's pretty apparent that you're not seeing the image on a CRT (it looks very flat, and there's no glare). Ozu's style comes in handy here, however, because the only way this effect can work at all is if you shoot straight on and never move the camera.

- There's a nice, reassuring appreciation of Ozu by Mindy Aloff that ran in the Times in 1994. Reassuring because it took her several films to really get Ozu.