The second part of Christopher Zane's interview of me (and probably the only time my words will run with a still from Josie and the Pussycats) is here. And I highly recommend you check out the rest of his blog.

Tuesday, October 09, 2007

Monday, October 08, 2007

#77: And God Created Woman

And God Created Woman, 1956, directed by Roger Vadim, screenplay by Roger Vadim and Raoul Lévy.

After 76 Criterion films, we finally arrive at straight exploitation. And God Created Woman has a joke of a plot, terrible acting, retrograde sexual politics, and exactly three good qualities: eye-popping colors, CinemaScope, and Brigitte Bardot. And the first two aren't that important. And God Created Woman is more colorful (and racist) than Black Orpheus, fluffier than Charade, more voyeuristic than Peeping Tom. You know pretty much what you're in for from the film's fifth shot:

Like I said, bright colors, Cinemascope and Brigitte Bardot. It's not too hard to figure out why this film caused a sensation in 1956. Of course, leering at Brigitte Bardot wouldn't be acceptable without some semblance of a plot. And that's exactly what Vadim and Lévy provide: some semblance of a plot. Bardot plays an orphan named Juliette who's living in foster care in St. Tropez. That silhouette on the other side of the sheet is a yachtsman and real estate developer named Eric Carradine, played by future Bond villain Curd Jürgens:

Like anyone with a Y chromosome, Mr. Carradine has unwholesome plans for Juliette. Unfortunately for him, she only has eyes for a local cad named Antoine Tardieu, played by Christian Marquand:

Tardieu is willing and eager to sleep with her, but wants nothing else to do with her. As the movie opens, Juliette's relationship with her foster parents has deteriorated to the point that she is using her foster father in his wheelchair as a shield to keep her foster mother away:

Like Helena in Autumn Sonata, this is the sort of filmic use of the handicapped that you are unlikely to ever see again on screen. Anyway, to prevent further wheelchair battles, Juliette's foster mother arranges to have her sent back to the orphanage. To avoid this fate, she marries Antoine's younger brother Michel, out of an unconvincing mixture of spite and desperation. Jean-Louis Trintignant plays Michel as a brooding, sensitive type with low self-esteem:

You can see where this is going: Juliette's sexuality is too wild and uncontrollable to ever be tamed by such a man as Michel; neither Antoine nor Carradine can resist her, scandal ensues, and so on. Along the way, Vadim puts Bardot in as many shots as possible, whether she's sullenly eating a carrot:

Or sullenly opening an umbrella indoors for some reason:

Or even not-so-sullenly putting on a dressing gown behind the most unlikely-to-actually-be-sitting-there ship model with a semi-translucent curtain in cinema history:

This isn't a narrative film so much as it's a peepshow, but as peepshows go, it's first-rate—if you're from the fifties and incredibly repressed. Still, the film does have its charms. San Tropez looks suitably picturesque:

The cinematography isn't brilliant, but there are some nice CinemaScope compositions (although virtually no closeups):

And although this was shot in Eastmancolor, a single-strip film that I thought was responsible for the faded look of many post-three-strip-Technicolor movies, it's very crisp and bright.

In San Tropez, even color is more saturated. None of that outweighs the terribleness of a film that takes it as a given that Bardot alone is responsible for corrupting the men around her. When Antoine sleeps with his little brother's wife, then walks off to tell his mother that they have to throw Juliette out of the house, there's hardly a suggestion that Antoine shares any of the blame.

And I'm not even going to comment on Juliette's final descent into alcohol-fueled madness, where she falls so far that she dances with black men:

Let's just say that the film leaves a lot to be desired, politically and sexually. Its principal value today is, as Nathan Rabin wrote for The Onion A.V. Club, "a historic bit of pop-culture sociology." As historic bits of pop-culture sociology go, this one's painless and easy to look at. Just don't expect a great film.

Randoms:

- Roger Vadim was married to Bardot at the time they made this film (he'd been dating her since she was 15 and he was 21, if his IMDB page is to be believed). I'm not sure if that makes it more or less creepy that he made a film whose principal attraction was staring at Brigitte Bardot, but I think it makes it more of an exploitation picture. This was Vadim's MO for the rest of his life: he dated Catherine Deneuve while directing her in Le Vice et La Vertu, and he was married to Jane Fonda when he directed her in Barbarella. I suspect Robert Rodriguez has studied Vadim's career closely. But given the relative fame and success of Vadim compared to Bardot, Deneuve, and Fonda, I think Rose McGowan may have paid more attention.

- About that film Le Vice et La Vertu: I haven't seen it, and hadn't heard of it until this evening. But it's an adaptation of the Marquis de Sade's Justine set during World War II, with Nazis. Which reminds me a bit of the hardest-to-watch-film in the Criterion Collection, made twelve years later.

- As attractive as Bardot is, there are at least two other bodies at least as curvy and attractive. Carradine's yacht:

- And his car, a Lancia Aurelia B24 Spider.

- Putting Bardot and the car in the same frame seems gluttonous, but here you are:

- A confession: a disproportionate amount of this site's traffic comes from people doing image searches for various actors and actresses (that, and middle school students looking for essays to steal about The Most Dangerous Game or Lord of the Flies). So, with a tip of the hat to Roger Vadim, here's one more picture of Brigitte Bardot, one of the film's few closeups. Greetings, internet horndogs!

Shameless Self Promotion

Tuesday, October 02, 2007

#76: Brief Encounter

Brief Encounter, 1946, directed by David Lean, written by David Lean, Noël Coward, Anthony Havelock-Allan, and Ronald Neame from the play Still Life, by Noël Coward.

Brief Encounter is the epitome of a genre that has completely vanished from cinema: the woman's picture.1 Jim Shepard memorably described this type of film as stories that:

...trundled through decades of forbearance: slow-moving, mile-long freight trains of self-denial. All those women gave up what they most wanted for somebody else's sake. Which meant that their movies centered on events that didn't happen: the singing career that wasn't begun, the wedding that didn't occur, the meeting in the park that never came off, the key phrase left unspoken. Which made for movies obsessed with the life not lived: a weird negative space of the never-was and the might-have-been.

Well, the one-two punch of capitalism and feminism seems to have pretty well put paid to self-denial as a filmic virtue. The demographic once courted by weepies now lines up to see chick-flicks, which offer a different kind of pleasure entirely: pure wish-fulfillment. Don't get me wrong, it's fantastic that we live in a culture where self-abnegation is no longer a universal female experience. But it's certainly stranded Brief Encounter. Shepard's essay dealt with the way Babette's Feast transcended the confines of the genre, but that's not how Lean's movie work: it's an exemplar of the form, not a film that challenges its boundaries. Appropriately enough, it opens with one of those mile-long freight trains of self-denial:

Okay, so it's a passenger train of self-denial, and it's moving at a good clip. But the main character's hopes and dreams might as well have been tied to the tracks for all the possibilities the film affords her. Lean cuts to a small refreshment room at the station, where the camera eventually settles on a couple quietly having tea:

That's Celia Johnson as Laura Jesson and Trevor Howard as Alec Harvey. Before we get to know much about them, they're joined at the table by Dolly, an older friend of Laura's who's talking as fast as the train that just passed. You can tell from Alec's expression how happy this makes them both:

Dolly prattles on and Alec and Laura are relentlessly polite. Eventually, Alec has to leave to catch his train. Later, we learn that this is the last time the two will ever see each other: Alec is leaving for South Africa. And that's the film in a nutshell: Laura and Alec's chances at happiness are continually, ruthlessly crushed—if not by those around them, by their own senses of propriety.

The rest of the story is told in an extended flashback, as Laura thinks over her almost-affair. That's when the film becomes difficult to take seriously, not because its cultural values are so alien, but because it relies to an insane degree on endless voiceovers. You know the kind of voiceover Scorsese uses in Goodfellas, where the narrator's words are belied by what you're seeing onscreen? Or the kind you see in films noir like Out of the Past, where you forgive the clumsy exposition because the story's moving so quickly? Or even the kind you see in adaptations of novels, where the screenwriter wants to capture something of the author's voice and can't come up with a better way to do it? Yeah, that's not really what David Lean is up to here. Instead, Brief Encounter is filled with basically static shots of Celia Johnson:

Over lines like this:

This can't last. This misery can't last. I must remember that and try to control myself. Nothing lasts, really—neither happiness nor despair. Not even life lasts very long. There'll come a time in the future when I shan't mind about this anymore, when I can look back and say quite peacefully and cheerfully how silly I was.

I did identify with Celia's character when she spoke those lines, but not for quite the reasons the filmmakers must have hoped. It's a shame about the voiceover, because when the film isn't relying on it, it's excellent. Lean captures the stifling, cramped quality of Laura's life brilliantly, and he doesn't need voiceover to do it. Take, for example, her husband Fred, played by Cyril Raymond as a well-meaning dolt who would never suspect his wife had any sort of inner life:

From what we see of Mr. and Mrs. Fred Jesson at home, his greatest passion is for crossword puzzles, not his wife. Here's the scene where she attempts to tell him she's met someone:

LAURA

I had lunch with a strange man

today, and he took me to the

movies.

FRED

Good for you!

LAURA

He's awfully nice, he's a doctor.

FRED

A noble profession.

LAURA

Oh, dear.

Beat.

FRED

It was Richard the Third who said

"My kingdom for a horse," wasn't

it?

LAURA

Yes, darling.

FRED

Well, I wish to goodness he hadn't,

'cause it spoils everything.

If he reminds you of Joylon Wagg, please be assured this is deliberate. Laura's life when she's not with Alec is so miserable that it lends credence to the one part of her voiceover that indisputably works: her reflexive hostility to everyone that surrounds her. This comes through in little moments like a scene where she's shopping at a pharmacy and briefly sees someone she knows socially.

Here's the voiceover:

That awful Mrs. Leftwich was at the other end of the counter wearing one of the silliest hats I've ever seen. Fortunately, she didn't look up, so I got out without her buttonholing me.

The tragedy of Laura's life is that she never lets anyone know what she's thinking, and we get the impression that half of what clicks between her and Alec is that they're willing to tell each other when the stifling pressure of English good form gets to be too much. They first bond at a modest restaurant when they're confronted with possibly the worst cellist in the country:

The single most attractive thing about Alec is that he's willing to respond in the only rational fashion:

That afternoon, in one of the movie's best touches, the pair attend a movie and are greeted with a grim surprise at the Wurlitzer.

And that's all it takes. Alec doesn't really do much, except pay a small amount of attention to what Laura is saying, and react to the absurdity of English cordiality with a bit of humor. But someone as miserably lonely as Laura doesn't need much. In the end, however, he is as unable to make any definitive steps toward happiness as she is. And because of the film's flashback structure, we know all along where this is going: both of them are too unwilling to break decorum to even have a proper goodbye.

Watching today, it's impossible to fathom this kind of miserable self-control, and it makes some of their love scenes seem absurd. They're the first screen couple I would describe as "solemnly in love." Apparently, their reticence provoked jeers even at early test screenings, at least for working-class audiences (the middle class, on the other hand, loved the film). They don't even kiss until 45 minutes or so in—but it's worth noting that their brief moments of physicality are one of the things the movie gets right.

Robert Krasker, the DP, shoots them like it's a noir. They embrace beneath train platforms, with the rumble and squeal of an express roaring by above them. It's one of the best things in the movie, dark and furtive, and even—dare I say it?—sexy.

Well, I may say it, but neither Laura nor Alec would. And what one remembers most about Brief Encounter today is not the love story, such as it is, but the moments of supreme English social awkwardness that Lean captures.

That's the two lovers caught at lunch by two bitchy friends of Laura's ("I do so envy you your champagne," one of them says). Alec has a counterpart scene of social humiliation when they are interrupted before finally consummating their relationship by the arrival of the friend Alec has borrowed an apartment from, the most sallowly unpleasant man in the world:

Neither Alec nor Laura can stand the social pressure: apparently, laughing at cellists is one thing, but doing anything to make yourself happy is quite another.

Brief Encounter is often called "the British Casablanca": a hyperbolic comparison, but a useful cultural barometer. It took the full terror of the Nazi war machine to stop Rick and Ilsa from choosing their hearts over their consciences. But in the British version of Casablanca, it took what, exactly? Fear of the disapproval of biddies in hotel restaurants? Laura's paralysis reaches apotheosis near the end of the film, when she realizes that Dolly has robbed her of any chance to say goodbye to Alec. This is her at her most desperate. The camera tracks in and tilts sickeningly (Carol Reed would be proud):

And at her moment of greatest despondence, Laura gets up from her table, runs to the tracks, and almost throws herself in front of a train. Just like she almost had an affair, almost consummated her relationship, almost left her husband. It's the film's best, sickest joke. Having failed to give her life any of the sweep of Anna Karenina, she is equally unable to recreate its finale. At least Anna got to fuck Vronsky.

Randoms:

- Trevor Howard also played Major Calloway in The Third Man. His performance here is so different that it took me half the film to recognize him.

- The original play took place entirely in the refreshment room where Alec and Laura meet. And apparently it did a great deal more with a subplot that's almost wholly superfluous here, a working-class romance between a conductor and a shopclerk that was contrasted against Laura and Alec's middle-class angst.

- Lean did the right thing by paring these two way back, but he might have done better by disposing of them entirely; they did nothing for me.

- Bruce Eder, who recorded the commentary track, hates the scene where Alec's friend interrupts the two of them at his apartment. He has a point: the rest of the film is scrupulously told from Laura's perspective, and she has no way of knowing what happened at that apartment after she left it. William Goldman eviscerated Saving Private Ryan on the same grounds (but with more cause: the whole movie is a flashback remembered by someone who wasn't there; at least Lean only has one scene with this flaw). But Billy Wilder apparently would disagree with Eder: he found Alec's friend so interesting that it gave him the idea for The Apartment.

- The sound mix is exceptionally sophistocated throughout, from the opening howl of a train whistle to the Rachmaninoff score.

- Laura's husband does get a moment of redemption at the very end of the film, and it's almost enough to make her sacrifice seem noble. Almost.

- There's a nice jab at the film industry buried in Brief Encounter. Alec and Laura see a trailer for a movie called Flames of Passion, which is the usual Hollywood bullshit: a woman tied to a burning stake, natives throwing spears, slightly unbelievable marketing slogans:

- But the best part of the joke comes when the actually go to see the film. Remember, the trailer looks like it could be for a low-rent version of King Kong. Check out the original source material:

1Not counting semi-ironic revivals like Far From Heaven, one of Shepard's jumping-off points.

Sunday, September 23, 2007

#75: Chasing Amy

Chasing Amy, 1997, written and directed by Kevin Smith.

Everyone has a moment when they're rudely forced to accept that they aren't as young as they'd like to believe. Martin Amis's day of reckoning came on May 21st, 1976, when the Rolling Stones played Earls Court. Here's what he wrote at the time:

Perhaps I'm too old for this sort of thing now—too old to buy fruitless discomfort at £1 an hour. I shouldn't have gone. I'm never going again.

He was 26. I'm not as precocious as Martin Amis, but I had a similar experience watching Chasing Amy. The film was released ten years ago this April; I remember seeing it on its initial run. It certainly didn't seem timeless, but neither did it seem to be bound to a particular moment in history. And even if it was, what of it? The time since leaving behind the yearly landmarks of college has been a more or less undifferentiated mass; certainly things haven't changed that much. But ask yourself (as I did): When was the last time you walked into a bar and the band looked like this?

The makeup, the hair, the flannel. And Pete's Wicked Ale. I must regretfully report that the world has moved on since Chasing Amy was released. This has unfortunate implications for me and my ever-more-out-of-date wardrobe, but it makes the film more interesting than it was the first time I saw it. Kevin Smith didn't know he was making a time capsule, but Chasing Amy is filled with small details of an era that you probably didn't realize was so long ago. All that's missing are those damn child-proof lighters with the plastic lock you had to rip out with your teeth. No, wait:

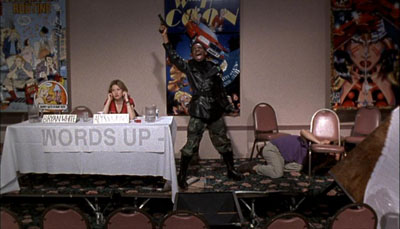

I stand corrected. Chasing Amy was shot during the long-ago days when comic book fans were still a unjustly-reviled subculture, before they talked the studios into making things like Ghost Rider and earned their revulsion. Appropriately enough, the movie opens at a comic-con. You know you're in the distant past from the first tracking shot: there are no studio publicists, no Harry Knowles, no A-list actors. Well, actually there's one A-lister, but he hadn't made it yet:

Ben Affleck plays Holden McNeil, a comic book artist who's sitting on the doorstep of commercial success. In plaid boxers.

That's his collaborator, Banky Edwards, played by the always-amusing Jason Lee. Holden and Banky's friendship is thrown into disarray when Holden falls hard for Alyssa Jones, a fellow comic book artist.

As in any romantic comedy, there's a complication, which once again pretty clearly dates the film to the mid-nineties.

That's Carmen Llywelyn—Jason Lee's wife at the time—making out with Joey Lauren Adams. This makes Jason Lee's great reaction shot all the more credible:

Alyssa's sexuality is just a stand-in for whatever the obstacle would be in any other romantic comedy; she could be seeing another man without much of a change to the film. It seems like more of a hook for Miramax's marketing team to seize on than an intregal part of her character. This is not to understate the importance of having an easy hook for marketing: this movie got distributed by a major studio for a reason. But Chasing Amy is more about Holden's jealousy than Alyssa's identity. And the best thing about the movie has nothing to do with either character: it's Jason Lee. He's the only member of the cast who moves smoothly through Chasing Amy's schizophrenic changes in tone. No matter how goofy the setup, Lee manages to make it funny. Smith stages a truly absurd scene near the beginning of the film where Holden and Banky heckle a black militant comic book artist (his book is called "White Hating Coon"). Sample dialogue:

HOOPER

They tryin' to tell us that deep

inside we all wants to be white!

BANKY

Well, isn't that true?

It's just as ridiculous as it sounds on the page (more than you can see in that excerpt even: Hooper is arguing that the Star Wars trilogy is about urban gentrification), and Hooper's response to his hecklers is equally ludicrous:

But I defy you not to laugh at Jason Lee's reaction shot:

It's cornball, and straight from the eighties comedies Smith drew on in Mallrats, but it cracked me up. So Lee's got that going for him. But when the scene calls for it, he manages to draw upon the kind of depths that Robert Downey, Jr. would be proud of:

Jason Lee's unexpected soulfulness is unfortunate for Ben Affleck, whose character is supposed to be the film's locus for angst. His name is Holden, for Chrissakes. Still, he's up against a lot: Kevin Smith lets Lee convey a lot about his character wordlessly. Affleck has to get the same information across while wading through grandiose speeches. Here's how he confesses his love to Alyssa, who has just bought him a chintzy painting:

I love you. And not, not in a friendly way, although I think we’re great friends. And not in a misplaced affection, puppy dog way, although I’m sure that’s what you’ll call it. I love you. Very, very simple. Very truly. You are the epitome of everything I have ever looked for in another human being. And I know that you think of me as just a friend, and crossing that line is the furthest thing from an option you would ever consider. But I had to say it. I just, I can’t take this anymore.

I can’t stand next to you without wanting to hold you. I can’t, I can’t look into your eyes without feeling that, that longing you only read about in trashy romance novels. I can’t talk to you without wanting to express my love for everything you are. And I know this will probably queer our friendship—no pun intended—but I had to say it, because I’ve never felt this way before. And I don’t care, I like who I am because of it. And if bringing this to light means we can’t hang out anymore, then that hurts me. But God, I just, I couldn’t allow another day to go by without just getting it out there, regardless of the outcome—which by the look on your face is to be the inevitable shootdown. And, you know, I’ll accept that. But I know—I know that some part of you is hesitating for a moment. And if there is a moment of hesitation, then that means you feel something too. All I ask, please, is that you just, you just not dismiss that, and try to dwell in it for just ten seconds.

Alyssa, there isn’t another soul on this fucking planet who has ever made me half the person I am when I’m with you. And I would risk this friendship for the chance to take it to the next plateau. Because it is there between you and me. You can’t deny that. Even if, you know, even if we never talk again after tonight, please know that I am forever changed because of who you are and what you’ve meant to me, which—while I do appreciate it—I’d never need a painting of birds bought at a diner to remind me of.

If that's how he responds to a painting, thank God she didn't get him a car. I have my own shameful history of speechifying, so the scene didn't exactly ring false to me, but nothing Affleck can do will make this word soup seem like it would have the desired effect on Alyssa (it does). And that's the reason the movie didn't work for me: Holden is such a sad sack that it's not credible that a straight, unattached woman would fall for him, much less a lesbian. On the whole, she seems to have a better time with Banky:

That's one of the Chasing Amy's best scenes: Banky and Alyssa trade war stories about cunnilingus while Holden sits silently by, embarrassed out of his mind. Say what you will about Kevin Smith, no other filmmaker has found quite as much comedy in the mechanics of sex. It may be a dubious honor, but this is really where Kevin Smith broke new ground, and why I believe he belongs in the Criterion Collection, even if I don't love his movies. Remember: as tame as it seems now, Clerks nearly got an NC-17 rating when initially released (it took Alan Dershowitz to convince the MPAA to give it an R). Mallrats, Smith's misguided attempt to graft his sensibilities onto the skeleton of a mainstream eighties comedy, was a misstep. But although Chasing Amy has the structure of a thousand romantic comedies, Smith successfully infuses it with a kind of grossout humor previously only plumbed by standups. Observe:

That's not the kind of thing you usually see in multiplexes. As funny as the scene is, Joey Lauren Adams's "can you believe I'm getting away with this?" expression illustrates the most dated thing about the movie. You can see it most egregiously when Alyssa affectionately calls another woman a cunt, but throughout Chasing Amy there's a self-congratulatory feel to the vulgarity that went out of style somewhere around the turn of the millennium. Come to think of it, there's a lot of self-congratulation going on throughout the film, which is packed with references to Smith's previous movies: Alyssa and Holden both knew the characters from Clerks (Alyssa went to the funeral that Dante and Randall ruined) and they both hung out at the Eden Prairie Mall from Mallrats. And of course, there's the obligatory appearance of Jay and Silent Bob. Actually, I kind of like what Smith does with these two; they're in the movie before they appear. Holden and Banky's success comes from a book based loosely on the duo called "Bluntman and Chronic":

From what we see of the comic book, they behave pretty much the way their characters did in Mallrats, which is to say they're completely insufferable. Late in the movie, they show up in person:

This gives Smith an opportunity for a moment of post-modern introspection, criticizing himself for the way he used these characters in his previous movie:

JAY

But that ain't like us at all,

all slapsticky and shit, run around

like a couple of dickheads,

saying... what's that shit he's got

us saying?

SILENT BOB

Oh, um, Snoochie Boochies.

JAY

Snoochie Boochies. Who the fuck

talks like that? That is fucking

baby talk.

Agreed. This sort of recursion is pap to fanboys, but it doesn't help Chasing Amy succeed on its own merits. In the end, for the film to work, we have to believe that Alyssa and Holden really connect, so much so that Alyssa is willing to redefine her sexual identity in order to be with Holden. It's kind of a stretch. The characters do work pretty well when their relationship is falling apart, however. The best-directed scene between Alyssa and Holden is the fight they have at the hockey match, where Holden's jealousy and insecurity finally gets completely out of control.

It's tightly paced and edited, even if the insert shots are on the nose, and it makes me think Smith could have a great movie in him if he weren't quite as in love with the sound of his own voice. But when the opportunity comes to have one character give a grand speech, Smith can't resist. Watching the movie, I was reminded of Frozone's description of Baron Von Ruthless's fatal mistake in The Incredibles:

He starts monologuing! He starts this, like, prepared speech about how "feeble" I am compared to him, how "inevitable" my defeat is, how "the world will soon be his," yadda yadda yadda.

In the end, Kevin Smith's fatal flaw as a screenwriter comes straight from the world of comic books. I like to think he appreciates the irony.

Randoms:

- Chasing Amy is second only to Armageddon when it comes to discussions of films that don't really deserve to be part of the Criterion Collection. I see where people are coming from, but I think you can make a case for it now that you couldn't when the DVD was released in 2000. In addition to being a time capsule from the mid-nineties in terms of what's on screen, Chasing Amy also represents a pivotal moment in the film industry. The movie came out towards the end of the time that people thought of "independent film" as a sensibility, rather than a financing model. Harvey and Bob Weinstein were just starting to peak, Miramax's stranglehold on the Academy Awards was well on its way. And as much as people dislike it now, it was very, very well-reviewed on its release. Still, reactions to its inclusion in the collection are, well, mixed. Here's Ben Affleck on hearing that Armageddon wouldn't be his only Criterion DVD:

- And here's the slightly-more-circumspect Joey Lauren Adams and Jason Lee getting the same news.

- The still of Alyssa and Banky trading cunnilingus stories is staged to match the scene in Jaws where Quint tells his story about the U.S.S. Indianapolis—note the matching booth and windows. You can make your own vagina dentata joke here.

- This scene contains Chasing Amy's other great profane film quote, this time from The Graduate:

- Look closely at that still and you can see Banky's hair, moving back and forth at the bottom of the frame.

- Like any Kevin Smith movie, there's a part for Brian O'Halloran. And like any Ben Affleck movie, there's a part for Matt Damon. They play a pair of obnoxious MTV executives who want to make an animated series out of Bluntman and Chronic.

- According to the commentary track, Damon's character was based on Mike De Luca, whose best days were still ahead of him.

- Kevin Smith quotes one other filmmaker in Chasing Amy, and it's an odd choice for the consummate New Jersey white boy:

- During the scene where Banky tells Holden how Alyssa got her nickname, Smith cuts to a direct-to-the-handheld-camera monologue that's straight out of Do The Right Thing. And yes, that's the convenience store from Clerks in the background.

- The film was shot on non-anamorphic 16mm for budget reasons, and the transfer really shows its grain. When Criterion released this on laserdisc, the director of photography corrected some framing errors in the original theatrical release, but when they did an anamorphic transfer for the DVD, they made the same mistakes all over again. So the DVD duplicates the theatrical experience, down to the shots where Jason Lee and Ben Affleck's heads are cut off:

- Speaking of budget, Smith alludes on the commentary to taking the film away from Miramax and then bringing it back, but doesn't elaborate. On the Criterion Forum, I found a link to this interview with Smith, in which he explains:

Chasing Amy was supposed to be a $2-$3 million flick, and the money was there for the taking, but we just didn't agree on the cast with Miramax. I wanted to use Ben, Joey and Jason, and Miramax was all about using other people. And so I had a meeting with [Miramax head] Harvey [Weinstein] where I basically lowballed it and said, "Look, man, we'll go off and make this movie with our cast for two hundred grand, and if you guys want it when we're done, fine. If not, we can take it to someone else." And he was completely sold. So we went off and made it, came back, and the dude fell in love with it. And now he loves my actors so much that they've been cast in other movies.

So with Clerks (financed on credit cards), Smith has now made at least two films completely on his own terms. In the case of Chasing Amy, he walked away from at least 1.8 million to get the cast he wanted. Whatever you think of his movies, I think you have to respect his balls. Also note that at the time the interview was conducted, The Onion couldn't take it for granted that their readers would have any idea who Harvey Weinstein was or what he did for a living. - As self-indulgently recursive as Chasing Amy seems, it could have been worse. The film originally opened with Holden and Banky meeting two scornful comic book owners. Their snarky comments about "Bluntman and Chronic" were taken directly from a negative review of Mallrats.

- Casey Affleck has a brief appearance in the opening scene, wearing a Watchmen t-shirt. From what I hear of his performance in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, he's come a long way.

- The fashions of 1997 are all the more embarrassing because I remember wearing them. But consider this: Ben Affleck is wearing his own clothes throughout the film (which were apparently stolen during the production). Every flannel shirt, every pocket-t, every pair of raggedy jeans was from the personal pre-fame wardrobe of the star of Armageddon. Movie stars! They're just like us! Until they can afford not to be!