M, 1931, directed by Fritz Lang, written by Thea von Harbou and Fritz Lang.

Wer ist der Mörder? Who is the murderer? That question is the starting point for any number of serial killer movies, from The Lodger to Identity. And the answer is usually pretty structurally simple: "That's him, officer," or "It was you, all along!" But although we see this question again and again in M, the movie isn't that interested in the answer, unless the question means something closer to "What is it like to be the murderer?" Even that's an oversimplification that doesn't cover the scope of Lang's achievement in M. This may be the best serial killer movie ever made; it also is one of the greatest police procedurals, portraits of a living city, movies about the criminal underworld, critiques of the media, and films noir.

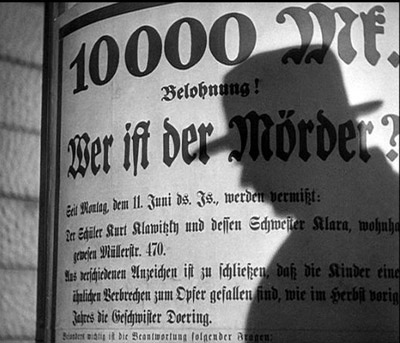

Fritz Lang made M in 1931, but it is shockingly modern in tone, subject, and technique. The plot is relatively simple: Peter Lorre plays Hans Beckhart, who is compelled to kill little girls. The police can't catch him; newspapers keep writing about him (his repetitive compulsions feed the news cycle), and the public is outraged. Increased police presence in the city is bringing organized crime to a standstill, and so both the police and the criminals are desperately searching for Beckhart. The audience knows who he is and where he is from the beginning: we see him the first time we see a "Wir ist der mörder" poster. The question and the answer are in the same shot.

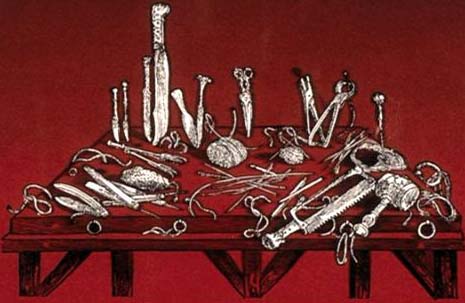

Lang has a real awareness of the myriad delicate relationships that keep a modern city moving; between upper and lower classes, between police and criminals, between the media and the public. You can see this most clearly in the scene of a police raid on a bar; Otto Wernicke, playing Kommissar Lohmann, checks the papers of everyone there, one by one. Lang lets the scene play long; we see three people go before the Kommissar, one with forged papers, one with real papers (but wearing a fur coat he's recently stolen) and one with no papers at all. Lohmann's interactions with these people are delicately played, but they show the very complicated power relationship between a good cop and career criminals. There's a certain fatherly affection present when Lohmann looks at fake papers, winks, and tells the bearer "You've been cheated." Although this is one of the most obvious examples, the movie is suffused with scenes in which complicated power and class dynamics are sketched out in very short order. He shows how these dynamics, carefully maintained, are pushed out of balance by the arrival of the child-murderer played by Peter Lorre; it's in everyone's interest that he be caught.

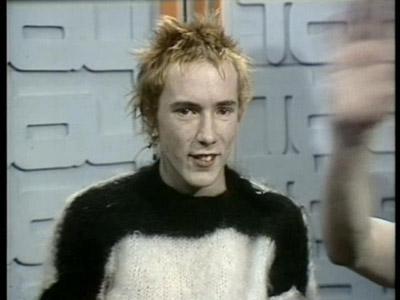

When you look at a movie like The Silence of the Lambs, it's clear that everyone involved in the project intended Hannibal Lecter to be charismatic and appealing. Even Kevin Spacey's killer in Se7en has his charm; he's just trying to teach us all a lesson. I always feel a little queasy about "cool" serial killers as characters, especially when surrounded with what's meant to be gritty reality (Se7en is a particularly bad offender here; in The Silence of the Lambs everything's so gothic that it's easier to discount Lecter). That's a little bit of a problem here; Lang doesn't ask or want you to sympathize with Beckhart; he's an evil man who does evil things. But Lorre's magnetic performance, particularly in the final scenes of the movie, makes him real in a way most on-screen killers are not. Here's his last monologue in its entirety. He's been captured by organized crime and is standing trial before a kangaroo court of criminals. He's just said that he can't help what he does, and someone in the crowd yells out that they all say the same thing when they're before a judge:

What would you know? What are you talking about? Who are you, anyway? Who are you? All of you. Criminals. Probably proud of it, too—proud you can crack a safe or sneak into houses or cheat at cards. All of which it seems to me you could just as easily give up if you had learned something useful or if you had jobs or if you weren't such lazy pigs. But me? Can I do anything about it? Don't I have this cursed thing inside of me? This fire, this voice, this agony?

...

I have to roam the streets endlessly always sensing that someone's following me. It's me! I'm shadowing myself! Silently...but I still hear it! Yes, sometimes I feel like I'm tracking myself down. I want to run—run away from myself! But I can't! I can't escape from myself! I must take the path that it's driving me down and run and run down endless streets! I want off! And with me run the ghosts of the mothers and children. They never go away. They're always there! Always! Always! Always! Except... when I'm doing it... when I... Then I don't remember a thing. Then I'm standing before a poster, reading what I've done. I read and read... I did that? I don't remember a thing! But who will believe me? Who knows what it's like inside me? How it screams and cries out inside me when I have to do it! Don't want to! Must! Don't want to! Must!

It reads a bit talky and overblown on the page, but when Lorre howls these lines at you, you can see the constant, unbearable pain Beckhart is in. In interviews, like the one with William Friedkin on the second disc, Lang says he doesn't intend for the audience to feel any sympathy for Beckhart; that said, he rarely cuts away from Lorre during the last scene, and when he does, it's usually to members of the criminal court nodding in agreement. Even Schränker only wants to kill Beckhart as a political exediency; he can't risk that he ever goes free again.

This was Lang's first sound film; he'd done fifteen silent movies (including Metropolis) and resisted the coming of sound, refusing to add sound to Frau im Mond despite the producer's wishes. Seymour Nebenzal talked him into it for M, though, and Lang didn't waste any time mastering the medium. In early sound films, the soundtrack is usually synched to what you're seeing on screen; Lang wasn't the first director to disassociate the two things, but he did it masterfully. He also understood that you didn't need sound at all, necessarily; witness the absolutely silent footage of police preparing for a raid. Lang keeps these scenes silent until a police whistle blows and then suddenly there's sound everywhere; the tromping of boots, people running to escape, shouting, more whistles, &c. It's fantastic. Some other experiments with sound are less successful; Lohmann's voiceover describing a police investigation while we're seeing the investigation doesn't add much (though it's better than a similar sequence in High and Low). Here's a closer look at a sequence where everything comes together, right at the beginning.

We've seen Elsie Beckmann bouncing a ball down the street after school; seen her meet Hans Beckert (she's bouncing the ball against the poster in the shot at the top of the page); seen them make small talk, seen him buy her candy and a balloon. This is intercut with footage of her mother wondering where her daughter is as time passes (we know pretty precisely how much time has passed, thanks to shots of the clock in Mrs. Beckmann's apartment—this movie is filled with literal ticking clocks). Mrs. Beckmann goes to the window and calls out "Elsie!" and then we get this series of shots:

The stairs of the apartment complex (this stairway-as-maze shot should look familiar; it's been used a million times since). Over this, we hear Mrs. Beckman call "Elsie!" again. This, and the shots that follow, are basically still images; there's no camera motion.

The attic of the apartment building. Again, "Elsie!" Nothing moves in this shot, there's no breeze on the eerily still clothes.

Elsie's place at the table. For the last time, increasingly desparate, "Elsie!"

This shot is silent. Elsie's ball rolls into frame and stops. We're on this for maybe five seconds; long enough to really feel a sense of dread.

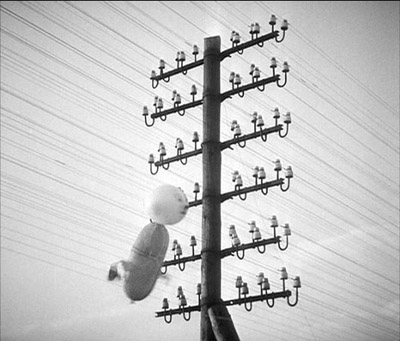

This shot isn't as long. Elsie's balloon comes into frame, gets snagged on the power lines for a few seconds, and then blows away.

We then get a dissolve to black, a few seconds of complete blackness, and then fade in on a newsboy yelling "Extra! Extra!" as he races down the street selling papers with the lurid details of Elsie's demise. It's a virtuoso sequence. A few take home lessons:

- Static shots can be used to increase a sense of dread. They also invite the viewer to look for what's missing, so in a sequence like this they work beautifully.

- Letting the viewer imagine what's happening to Elsie is far better than showing it, especially if the viewer has to make a few mental leaps (that's her ball, that's her balloon). Put the viewer in the mother's mental state immediately before and he or she will imagine the most horrible thing ever.

- Use sound judiciously. Some shots are better without it.

This is a movie I'll be coming back to again and again; there are hundreds of practical decisions Lang made that are easy to suss out and I imagine (and hope) they will inform my screenwriting from here on out.

Randoms:

- The new two-DVD set was something I had to buy; nobody in Los Angeles was renting it. I'm very glad I did; it's an embarassment of riches. For one thing, the movie itself was restored from the original camera negative; all earlier restorations were done from later prints.

- You'll notice in the stills above that the aspect ratio is pretty narrow. Early German silent film was shot at 1.33:1, close to Academy ratio. When they added sound, they simply put an optical soundtrack on the filmstrip, cutting into the picture and producing a 1.19:1 ratio. All earlier restorations were done with a telecine set to 1.33:1, which produced a white cropping line across the top of the image. This includes the earlier 1 DVD Criterion edition. The new, 2-disc set was done correctly and it looks great, as you can see in the stills.

- The information above is from the second disc, which includes "A Physical History of M", a rundown of all the various cuts and transfers of the film. Most interestingly, it includes footage from The Eternal Jew, a Nazi propaganda film that pointed to "the Jew Peter Lorre's" performance as an example of the kind of depraved character jews were naturally inclined to play. The section of the movie included is a rogue's gallery of decadent Jews, including "the relativity-Jew Einstein, who concealed his hatred of Germany behind obscure pseudoscience." I think Einstein would have had something to say about that if Germany had stayed in the war a little longer.

- One other lesson from M for filmmakers and especially editors: cutting on an action, that's cool. Cutting on an action that's followed through by another character in a different scene to connect the two character, that's very cool. Having a crime boss say the first half of a sentence and begin a sweeping arm gesture, and then cutting to a police chief finishing the sentence and completing the gesture: that's unbeatable.

- I much prefer commentary tracks where all parties are in the same room talking to each other; Criterion so far has frequently used commentaries that are edited together after the fact. I like knowing how the people talking feel about each other (Fight Club is a great one for this; Chuck Palahniuk clearly loathes screenwriter Jim Uhls, and their joint commentary is a masterpiece of passive aggression; plus David Fincher and Edward Norton do all they can to ignore anything Brad Pitt says). Anyway, on this DVD, Anton Kaes and Eric Rentschler share a commentary track, and they don't get along too well either. Rentschler is very bare-bones; Kaes goes on and on a bit. The basic structure is that Kaes will make a point, and expand on it for a while, until Rentschler gets frustrated and tells him he's wrong. Sometimes, Kaes bounces back from this, and the results are spectacular. For example, Lang tells a great story about meeting Josef Göbbels, being offered the mantle of Nazi filmmaker, and fleeing Germany as soon as possible (you can hear him tell this story on the second disc, in Conversation with Fritz Lang, a movie William Friedkin made about a year before Lang's death. Unfortunately, the story isn't true; Lang went back to Germany several times after his "flight," and he may not have met Göbbels. After Rentschler points this out, Kaes says—and I'm not making this up—something to the effect of "but regardless of the 'truth-value' of this story, don't you think the way Lang tells the story says something about his greatness as a filmmaker?" "Truth-value." Really!