Peeping Tom, 1960, directed by Michael Powell, screenplay by Leo Marks.

I can't remember who said it, but here's a bit of career advice. If you've never directed a film, you're supposed to accept any piece of crap directing job you can get, just to get your name on a feature film, any film. Once you've convinced someone to put you behind the camera, even if that camera is filming How To Stuff A Wild Bikini, you're a director, and every other job is just arguing over your fee. One of the reasons this is good advice is that career-killing movies are very, very rare. Try it: how many can you name? Heaven's Gate slowed Michael Cimino down but it didn't stop him. Kevin Costner not only worked after Waterworld, he worked after The Postman. The only honest-to-God "last movie you'll ever make" film I can think of is Ishtar. That, and Peeping Tom. Here's Michael Powell in one of the last happy moments of his career, at the premiere:

Powell is on the left; to the right are screenwriter Leo Marks1, star Karl Böhm, and actress Pamela Green. They may as well have been sailing off on the Titanic. Here's how Böhm described the evening in an interview for A Very British Psycho, a documentary about Leo Marks that's included on the disc. I've kept his German syntax intact:

The first time when I remember I saw it when I came to London for the official opening. What then happened I can never forget in my life. There were some very famous people invited as honorable guests, and Mickey Powell and myself, we stood outside in the foyer, and um, when the film finished there was an absolute deadly silence and we stood there and the doors opened and first at the doors were the honorable guests, the guests of honor were there. And then they came down, and they walked towards us, and suddenly they turned to the left, and they went outside even without looking at us—without shaking hands, oh well forget it, but they weren't even looking at us, as if everything would be stinking what's down there. (?) We were speechless, we looked at each other, we waited till somebody at least would comment, but nothing.

It was the reception Bialystock and Bloom dreamed of. Powell was less thrilled, however, and it was more or less the end of his career. Critical reception of the movie was sensationally vitriolic and spiteful. The Observer's C. A. Lejeune went so far as to leave out any of the actors' names, writing instead, "I don't propose to name the players in this beastly picture." Most of the reviewers seem personally disappointed in Michael Powell (who, with Emeric Pressburger, had directed a number of less seedy films, including The Red Shoes). I was reminded of Tibor Fischer's line about Yellow Dog: "It's like your favorite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating." After a thorough shellacking in the press, Peeping Tom was pulled from distribution and more or less disappeared. Michael Powell finished the movie he had begun shooting while Peeping Tom was in post, then fled to Australia, where he worked mostly in television.

So why did people hate Peeping Tom so much? And what's it doing in the Criterion Collection now? The first shot provides a pretty good clue:

Yep, this is one of those movies that implicates the audience for enjoying watching bad things happen on screen. Karl Böem plays the Peeping Tom of the title, a nice young man named Mark Lewis. We only see him behaving like a typical Peeping Tom a few times, though, looking through the ground-floor windows of his house (he has lodgers):

But Mark doesn't really like watching things with his own eyes. His real passion is for recorded experience. Specifically, the recorded experience of women's deaths. In addition to his day job as a focus puller and his sideline as a pinup photographer, he has a third part-time job: making snuff films for his own enjoyment. Here he is in his private screening room, rising from his chair as one of his movies (and, perhaps, its director) reaches a climax:

If this looks unpleasant and sordid, it is. And make no mistake about it: Mark's world is not the seedy-yet-glamorous one that you sometimes see in films set in and around pornography. Here, for example, is Mark's employer for his nude photo shoots, showing a customer a book of "views," as he calls them:

The actor's name is Bartlett Mullins; his rosy-cheeked priggishness sucks all the allure out of a room pretty quickly. The customer, by the way, is Miles Malleson, a character actor who was known by 1960 for playing absent minded, doddering old men, usually in comedies. In other words, the epitome of a"kindly old man." Here's how he appears just seconds later:

I used the Fischer line about a beloved uncle masturbating in a schoolyard advisedly. In fact, his raptures are interrupted when a schoolgirl comes into the shop—he carries out his book of pornography (he buys the whole lot of pictures), neatly wrapped in a brown paper bag labeled "EDUCATIONAL BOOKS." Now there's a character the audience doesn't mind being identified with!

But surely the embarrassing nastiness of the business end of pornography doesn't extend to the women themselves, you're saying, and to some extent, you're right. After all, one of the models is played by Pamela Green, a real-life fifties pinup. And it's true, she's easy to look at:

Of course, one of the first things she says to Mark during her photo shoot is, "Fix it so the bruises don't show." Worse yet is the other model, there for her first nude shoot:

Lovely. Until she turns, revealing a spectacular harelip:

Well, as she tells Mark, "You needn't photograph my face." It's not hard to see why viewers responded passionately to a film that insists, again and again, on punishing the audience for the act of watching. Powell needs the world of Peeping Tom to be this disturbing and degraded, however, because Mark Lewis isn't the movie's villain. There's no tough-but-noble cop on his trail, as in most serial killer movies. Here's our hero at his most noble and troubled:

For the film to work, you have to believe that Mark was produced by his environment. He's the opposite of Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs in every way; shy, poorly spoken, sweet in a painfully awkward way. Hitchcock did a similar thing with Norman Bates in Psycho the same year, but with a crucial difference: we don't know Norman's a killer till later in the film (or we wouldn't, if we were seeing the film for the first time in 1960). The first scenes of Peeping Tom, on the other hand, show Mark murdering a prostitute, filming the murder, watching the film, and then filming her body as police carry it out of her apartment. So making Mark sympathetic is a little more... challenging. Powell succeeds at this because of the fumbling romance between Mark and Helen Stephens, his downstairs lodger, played by Anna Massey.

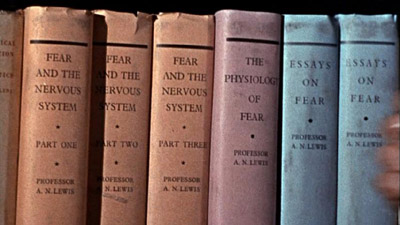

Helen is a bit of a wallflower in a way that is appealing to Mark. Although she is having a birthday party when we first see her, for the rest of the film she is almost always seen alone with her blind, alcoholic mother. As one would expect in a movie where seeing is almost always a predatory act, the mother is the movie's moral center, able to sense that something is terribly wrong with Mark. Yet she can't tell precisely what Mark's sickness is, even when she sneaks into one of his private screenings. She urges him to get help, which he seeks from a psychiatrist assisting the police investigation of one of his killings. But psychatrists are the problem, not the solution; as we see in some old home movies, Mark's scopophilia (or scoptophilia, as one of the film's psychiatrists incorrectly calls it) was deliberately induced by his father in the interests of science. Mark, it seems, was his father's test subject for at a study on fear that spanned at least six volumes:

When psychiatry is as predatory as pornography, and pornography as predatory as filmmaking, there's not much hope for a happy ending. Helen's dreams of a life with Mark (she plans to collaborate with him on a children's book called "The Magic Camera) amount to a sick joke about her naïveté. Mark has his own magic camera, and it's not suitable for children.

As you can tell, the film is filled with gallows humor and jokes about the movie industry. Mark is working on a movie called The Walls Are Closing In, and if you look at the incompetent director's chair (and are familiar with the Boy Scouts), you can spot Powell having a joke at his own expense:

It's not "Vivian Darkbloom," but it'll do. The film-within-a-film stars a difficult redheaded ingenue who is completely unable to act, constantly infuriating the director. Powell, of course, famously didn't get along with Moira Shearer, another redhead, during the filming of The Red Shoes. But apparently having an airheaded actress as Shearer's stand-in wasn't exquisite enough a revenge. Powell actually casts the real Moira Shearer as the film actress's actual stand-in, a woman edging past her prime who dreams of stardom while technicians adjust the lighting for the real actress.

If that weren't enough, he has Mark kill her. The sequences surrounding her murder and its aftermath are the movie's best, in my opinion: we see her death through the viewfinder of Mark's camera, as in earlier sequences:

This is intercut with normal footage of her as the scene reaches its conclusion:

Later, we see Mark developing his footage:

Finally, in my single favorite shot in the film, Shearer's face turns into something ghostly as Mark stands in the path of his movie's projection:

So does the movie hang together? In my opinion, not completely. Powell has two goals here that aren't entirely complementary. He wants to make a critique of the act of looking, but he's stuck with some of the conventions of serial killer movies. Doing both requires giving Mark's camera more power than I think it possesses. Towards the end of the film, Mark knocks out a window of his apartment to film the police storming his building (he is, as he tells a coworker, making a documentary about the police investigation into his hobbies). Well and good—but when one policeman tells the other "It's only a camera," it strains belief to have the other respond, "Only?" Powell may give the camera this kind of totemic power, and Mark certainly does. But policemen do not, and Powell overreaches here. Of course, it's impossible to give directors too much godlike power when your audience is other directors, and I think this is why Peeping Tom was championed by Scorcese and Coppola as a lost masterpiece. It's not—but it is very, very good.

Randoms:

- Leo Marks, who wrote the screenplay for Peeping Tom, led a more interesting life than any of his characters. He was perhaps the best British cryptographer not working at Bletchley Park during World War II, serving as spymaster for the SOE. One of his most noteworthy innovations was using original poems as keys for spies, rather than works that might be stumbled upon by German codebreakers. To this end, he actually wrote many of the poems they used; one, beginning "The life that I have/Is all that I have/And the life that I have/Is yours," became mildly famous in its own right. A Very British Psycho also gives him credit for inventing the one-time-pad, which is a somewhat dubious claim, given that Vernam and Mauborgne held the relevant patents before Marks's tenth birthday. His innovations in practical cryptography for undercover agents are undeniable, however. In any event, credit Marks's cryptographic background for the film's verbal playfulness.

- Scorcese, a fan of all things Michael Powell-related, had Marks give the Devil his voice in The Last Temptation of Christ.

- Peeping Tom features the first nudity in British cinema. Here's Pamela Green moments before Mark ends her life (offscreen):

- Green was a real-life pinup model, and runs a website featuring some of her work from the fifties. The site also includes her recollections of the shooting of Peeping Tom. Of course, I only read her website for the articles.

- Michael Powell seems to have been quite determined to have as many looping self-referential traps in Peeping Tom as possible. He played Mark's cruel and exploitative father in the flashbacks. Here he is giving young Mark his first camera:

- The young boy who Powell makes cry was played by his own son, and the corpse of his mother was convincingly played by his wife and son's mother. He's interviewed for A Very British Psycho, and seems remarkably untroubled by the experience. I'd be interested to know whether his apartment has a darkroom.

1Actually, second from the left is Stuart Levy, Vice President of Anglo-Amalgamated, the film's production company; hat tip to Steve Crook of The Powell and Pressburger Appreciation Society for the correction. I am, as it turns out, half German and half Anglo-Amalgamated myself, so I should have known this...

Interesting (and hilarious) that Powell himself once noted that Peeping Tom was "a very tender film, a very nice one." Do you imagine he really believed that? Perhaps he saw a very different film in his mind's eye than everyone else did. If so, what do you think was lost in translation to the screen? You know, of the uh, so-called tender and nice qualities...

ReplyDeleteIt's very much a Fairy Tale...think Beauty and The Beast without the happy ending, the curse being the camera itself...all those developing clocks ticking towards 'Midnight' too...I think Powell saw Mark Lewis less as a psychopath, more as a filmmaker, so he was bound to be better disposed to him.

ReplyDeleteDo try and see this in a cinema with an audience...you will be amazed the power this 45-year old film still has. A different level of achievement than, for example, Psycho..

Good essay my friend..

Anonymous 1:

ReplyDeleteI hadn't read that Powell quote—thanks for passing it along. think that filmmakers have an unlimited ability to see different things in their films than an audience does, so I suppose it's possible he believed it. He certainly tries to be as sympathetic to Mark as possible—so I wouldn't be too surprised if he missed just how nasty the film ended up being.

Anonymous 2 (this is like Thing One and Thing Two in The Cat and the Hat): You're right about the fairy tale aspects, which I more or less missed. The Magic Camera, indeed. I saw it years ago with an audience on a scratchy 16mm print. It's defninitely more frightening that way, and it is certainly a more modern film than Psycho, which I think has lost most of its ability to shock and scare. But I think Psycho is the cleverer film, because it has such an interesting structure.

Very nice, thanks.

ReplyDeleteBTW, that's not Leo Marks in the photo at the premiere of PT, it's the vice-president of Anglo-Amalgamated (the production company), Stuart Levy.

Most dictionaries allow "scoptophilia" and "scopophilia" as acceptable variations on the same word.

And no, Columba, Powell's son, doesn't have a dark room :)

Steve

--

Steve Crook

The Powell and Pressburger Appreciation Society

http://www.Powell-Pressburger.org

Steve, thanks for the heads up re: Stuart Levy. I've corrected the caption and credited you. Your site, by the way, is an invaluable resource—I got a great kick out of reading the vitriolic reviews of Peeping Tom. I was actually pretty surprised they weren't quoted in more detail in A Very British Psycho, since they had so much to do with what happened to the movie.

ReplyDeleteRe: scopophilia and scoptophilia, I always thought scoptophilia came into existence as the result of a typo in a dictionary of psychiatry. You're right, though—my OED has it as an acceptable variant (though googling it shows it to be quite rare in modern usage). And perhaps Marks and Powell had that character use an archaism deliberately, to expose his lack of useful knowledge...

Re: Columba, that's reassuring.

The Peeping Tom vs. Psycho debate reminds me of a comment Armond White made, in relation to the two big war movies of 1998, The Thin Red Line and Saving Private Ryan (which was Armond's favorite of the two):

ReplyDelete"What is this war in the heart of cinema? Is there one cinema, or two?" Basically, Armond thinks of both Peeping Tom and Thin Red Line as the theoretical, effete versions of the more muscularly narrative-based works of Hitchcock and Spielberg.

Describing Psycho as "muscularly narrative-based" is interesting because Psycho is the film with the obvious narrative flaw: the final scene with the psychatrist that goes nowhere. Which reminds me of this, from Martin Amis:

ReplyDeleteThe most muscular literary critics on earth have no equipment for establishing that:

'Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears'

is a better line than

'When all at once I saw a crowd'

- and, if they did, they would have to begin by saying that the former contains a dead expletive ('do') brought in to sustain the metre."

I found Armand White's review here. It's interesting—I think he makes a good case that De Palma has been robbing Powell more than Hitchcock over the years.

I stumbled upon your blog through kottke.org, and I'm very glad I did. To echo many other comments: your writing is terrific and muy entertaining.

ReplyDeleteI was especially gratified to read this review of Peeping Tom, complete with new creepy stills that I can use for my own nefarious purposes.

I went into a screening of that film as a defenseless college freshman; I came out a woman.

A disoriented woman.

Lanyard,

ReplyDeleteGlad you're enjoying the site. And feel free to borrow the stills.

I saw Peeping Tom for the first time in college, as well. Didn't come out of the screening a woman, though...

Matt

I gotta wonder if John Carpenter did'nt see Peeping Tom somehow, at some point. I know he always cites Touch of Evil in relation to Halloween (and then there's the POV shots in It Came From Outer Space), but....

ReplyDeleteThere is no question, however, the Micheal Mann is a big fan of this movie. Exhibit A: Manhunter.

JJ,

ReplyDeleteI wouldn't be at all surprised. And good catch re: Michael Mann—I really gotta see Manhunter again.

There is one udder almoost career-killing moovie that I can think of: Straight to Hell. After Repo-Man and Sid & Nancy, the atom-bomb proportions of this film disaster nearly destroyed Alex Cox, who yet went on to make small indie/European films and documentaries. He has yet to be trusted with a substantial movie to direct again.

ReplyDeletemoocow,

ReplyDeleteWell, there you have it. But was Straight to Hell ever supposed to make money? The way he tells it on his website, it was just sort of a lark because a concert he was trying to get together never got off the ground.

MooCow,

ReplyDeleteYou sure it wasn't Walker that really killed Alex Cox?

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete