The 39 Steps, 1935, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, adaptation by Charles Bennett, dialogue by Ian Hay, from the novel by John Buchan.

Nobody but paranoiacs goes to see a paranoid thriller for penetrating insights into the inner lives of the characters. There's no sense in this kind of movie wasting any time putting the characters into mortal peril; nobody wants a long scene of Roger Thornhill pitching a new ad campaign. But no other thriller streamlines the main character's life as drastically as The 39 Steps. Robert Donat plays the main character, Richard Hannay, who is in the wrong music hall at the wrong time, and ends up, as Hitchcock heroes tend to, on the run from both criminals and the law. Everything we know about Hannay's life emphasizes how sketchily drawn and temporary his life is before the movie begins, from cardboard letters in his apartment lobby:

To the apartment itself, where the furniture is still covered in sheets:

All the movie tells us about him is he's in town for a short time on business and he's Canadian. But as you can see from the sets, Hitchcock does everything he can to impress upon us that Hannay isn't carrying much of a back story with him. Hannay's life really begins when the movie does, at a music hall performance of an impresario named "Mr. Memory." Mr. Memory gets only a few minutes into his act before someone pulls a gun:

Unfortunately for Richard Hannay, the gun is only seen in a tight shot—so when Lucie Mannheim asks if she can come home with him after the show, he thinks it's just because he's so damn charming.

Actually, it's not clear what Hannay thinks, or why he agrees to bring a stranger home with him; he doesn't seem to want to sleep with her (though he does serve her fried haddock, which may be some sort of British code: "so I fried up a haddock, and I'd only met her that night, wot wot!"). Anyway, she tells him, through a thick German accent, that her name is "Annabella Smith," and she's being pursued by men who want to kill her. She adds "something which is not very healthy to know:" unless she can stop it, a vital Air Ministry secret is about to be smuggled out of the country. Hannay, so trusting when it comes to inviting strangers to his apartment, doesn't believe a word of her story. But she proves most of it (particularly the "not very healthy to know" part) that night by staggering through his door and collapsing with a knife in her back.

Yes, this is a movie where someone staggers through a door and collapses with a knife in their back. Hannay quite sensibly goes on the lam, and the rest of the movie is basically an extended chase scene, where nobody is quite what they seem and one safe haven after another turns out to be perilous. The first section of Hannay's flight relies almost entirely on paranoid thrills. There's a standout action sequence as the Flying Scotsman crosses the Forth Bridge:

The dominant tone here is not the Indiana Jones-style action that the still above would imply, though; more frequently Hitchcock goes for the kind of tension you can see in this shot, later in the same sequence:

Will they see him? Will he fall? This shot is interesting, actually, because the framing is very self-conscious in deliberately denying the audience important information. Hitchcock tracks right with the train, and when he tracks back to the girder, Hannay is gone; we never find out exactly how he got off the bridge. It's a very self-conscious use of the camera. As with the tight shot of the gun, you can't help but be aware that you're being told the story in a particular way, by a particular narrator, because the framing is so obviously limiting. And if you think of the camera as a narrator, then you have to admit that this one is Nabokovian in terms of sheer manipulativeness. Manipulative is an apt word, actually, because the most obvious example is a long shot at a party where the appearance of one character's hand is a significant clue. The first time you see the scene, you don't notice anything strange about it, right up to the reveal shot:

But the second time you see the sequence, you notice how oddly a lot of it is framed to include other people's hands:

It's the cinematic equivalent of Pnin's birthday (O careless reader!)—like Nabokov's narrators, whoever is controlling the camera here knows there's a clue you're not paying attention to, and is not above taunting you a little. Hitchcock's obvious presence in this film was almost enough to induce me to follow the bouncing ball from privileging mise en scène to embracing auteur theory. But there's a reason Hitchcock's thrillers are so beloved of auteurists: thrillers aren't character studies, and a director has a great deal more control over how and when visual clues are given in a movie where the plot depends on reveal shots. It's easier to be an auteur if you work in a genre that minimizes the contributions of writers and actors.

That's not to say the actors don't turn in great performances, just that this is the kind of movie where actors must be unflappable and charming, not necessarily insightful. Basically, it's the kind of movie you want to cast stars in. That's right, I said stars, plural; there's a romantic female lead in the movie too, Madeleine Carroll:

You might be wondering why I haven't mentioned her before. It's because she doesn't show up at all until 25 minutes into the film, when Hannay ducks into her compartment on the Flying Scotsman, kissing her passionately so the cops will walk by. You can tell by the look in her eyes that this tactic is going to have... limited utility:

This scene prefigures Eve Kendall's voracious seduction of Thornhill on the 20th Century Limited in North By Northwest, but Hannay could take a few pointers from Cary Grant. Hannay's approach is nearly charmless, and Carroll turns him in as soon as she can. In fact, you could plausibly retitle The 39 Steps as The Importance of Being Charming, because Hannay only succeeds when he's being charmingly dishonest; nearly every time he's honest about anything, he immediately falls into worse trouble.

The movie itself gets a lot more charming when Madeleine Carroll reappears (after the train incident, which lasts maybe sixty seconds, she takes a half-hour vacation from the movie). Up to that point, it's a paranoid thriller with some hints of tragedy (I'm thinking here of Peggy Ashcroft's brief turn as a beaten-down wife, the most nuanced performance in the film). Once Carroll comes back, it undergoes a sudden transformation into a romantic comedy. This change isn't completely abrupt; Hitchcock leads into it with a comedic scene where Hannay hides out in an assembly hall, is mistaken for a visiting speaker, and gives a passionate oration:

This is probably my single favorite scene in the movie. The speech Donat gives is hilarious ("I know what it is to feel lonely and helpless and to have the whole world against me, and those are things that no man or woman ought to feel!"); this is the point where he quits worrying and just starts enjoying the ride. You can see that when he's escorted out handcuffed to a detective, cheerfully waving to the audience.

So it's not completely tonally unprecedented when the last half hour of the movie becomes primarily about Donat and Carroll bickering and fighting and falling in love. There's no denying it's a shift in tone, though. It's a long way from this shot of Hannay at the most tense and suspicious dinner ever:

To the screwball comedy aspects of Hannay and Pamela's completely unconvincing impersonation of newlyweds:

It shouldn't work to have such a dramatic shift in tone two-thirds of the way in, but it all kind of hangs together. For one thing, the last third is a good screwball comedy. Though they're handcuffed together, Carroll always looks that terrified, Hannay always looks that phony, and he's obviously holding a gun against her, the old woman they're fooling is thrilled. For another thing, some of the complications of being handcuffed together are not just funny but sexy. Take Hannay's hand on Carroll's leg when she removes her wet stockings:

Finally, the tone changes back again by the end, a giant, tense, finale of a set piece. Fittingly, it's at another music hall, and comes complete with a John-Wilkes-Booth-style leap from the balcony:

When people praise thrillers, they often describe them as "tight." You can't say that about The 39 Steps. The plot's kind of shambling, characters appear and disappear, one of the leads is only in about a third of the movie, the tone varies wildly, and nobody seems to care too much about the murder that the movie opens with or the government secret that closes it. But it goes from paranoid and strange to charming and funny and back again so smoothly that you don't notice a change, the plot is surprising the first time you see it and the jokes are funny the seventh, and you could write a book about the deliberate way Hitchcock places and moves his camera. The 39 Steps is genre filmmaking at its best (and I love genre films). For one thing, when it comes to thriller/romantic comedies (for further examples see North By Northwest and Charade), this is the movie that invented the genre.

Randoms:

- Hitchcock shot his first movie at UFA and there's a German Expressionist influence in this film. Like this bizarre shot of Richard Hannay's hallway, where the statue points at the window the murderer has just fled through:

- Or the closeup of Mr. Memory:

- Not much else to say about those except yeah, they're German Expressionist looking, all right.

- Pay special attention to the sequence where Annabella Smith dies for what may be the earliest use of an unanswered phone as a device to build tension. The desire to answer the phone is so Pavlovian that it can make an already tense sequence nearly unbearable.

- The DVD also includes the Lux Radio Theater production of the movie. Lux Radio Theater was a weekly program that presented radio versions of Hollywood movies. There's something really fun about seeing how they compressed the movie into a short radio program and attempted (more or less unsuccessfully) to translate the visual language of the movie into radio (hint: sound effects!). Still more fun is the intermission. Cecil B. DeMille, the show's producer, interviews Major C. E. Russell, a retired spy (whose book is still in print). The interview quite deliberately devolves into an ad for Lux soap, thusly:

Russell: There's a machine recently developed in this country...it could etch a map of the entire country on a single Lux flake. And that's probably the finest thinnest, and most fragile thing that I can think of for the moment.

Simpler times, simpler product placement.

DeMille: I know that you can read through a flake of Lux, Major! It's actually only two one thousandths of an inch thick!

Russell: I see! Almost as amazing as this machine I'm speaking of!

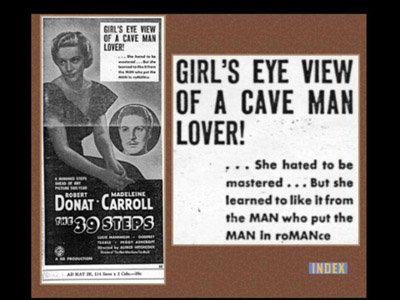

- And speaking of simpler advertising, the advertising for The 39 Steps really is something to behold. The DVD reproduces the original press book, complete with all the film's taglines. Now remember, the movie's about a man who is falsely accused of murder and flees across the country, trying to expose a ring of spies. See if you can tell what's strange about this poster:

- Donat is the MAN who put the MAN in roMANce because he had just starred in The Count of Monte Cristo. That wasn't even the most misleading tagline; that honor goes to this gem: "She Loathed Him... He Despised Her... And So They Were Married." Well, no. No, they weren't, unless you read a lot more into them holding hands at the end than I think is warranted. Apparently, marketing teams had just as much trouble selling genre bending movies in 1935 as they do now.

- The most unintentionally funny shot is the stock footage of an autogyro chasing Hannay across the moors:

- If that's the secret "vital to England's air defense" that people are dying to keep out of enemy hands, I say they just let it go.

How do you favor mise en scène over auteur theory when the director is the one primarily responsible for determining what's in the frame?

ReplyDeleteSorry, I guess I wasn't clear. What I meant was that the way Hitchcock uses mise en scène so obviously in The 39 Steps was almost enough for me to privilege mise en scène; and that doing that would lead me straight into auteur theory. Which my limited time around a studio has lead me to believe is mostly a convenient fiction.

ReplyDeleteAuteur theory works for movies directed by auteurs. I suppose that when you're in the context of Cellular, King's Ransom, and Blade Trinity, there might be a creative vacuum...but you're also at the home of A History of Violence and The New World.

ReplyDeleteHowdy, Matt.

--Jeff McMahon

Hi, Jeff—it's been too long!

ReplyDeleteI can't say much about The New World, not having seen it, but look, you can say that A History of Violence reflects Cronenberg's unique perspective and so on, but you don't think that Wagner and Locke get some credit for coming up with the characters and situation? Or Josh Olson, who came up with the structure, all of the dialogue (that wasn't straight from the novel), and the ambiguous ending (part of the pitch that got him the job writing it)? Or the actors? Even if you forget all those guys, don't you think that Cronenberg's team of people, Shore, Suschitzky, Sanders and Spier should get some of the "authorship?" I don't mean to minimze the director's unique contributions to any film, or deny that directors put their unique mark on anything they work on, some more than others. But so do writers, cinematographers, producers, editors, and so on. I just don't think anybody gets to be called the "author" of a studio movie, except as a shorthand.

And by "studio movie" I mean, "not written, directed, starred in, produced, edited by the same person, no matter where the money came from. Oh, also, if you liked King's Ransom, just wait for The Cleaner, coming to theaters from New Line Cinema in 2007. These are exciting times, my friend, exciting times!

ReplyDeleteSure, I agree that all the people you mentioned deserved credit for their individual contributions, but in the end the movie that you see on the screen was all filtered through Cronenberg's consciousness. The usefulness of auteur theory is that it provides a map for picking out the interesting things in a film, deciphering how to 'read' it. I don't know what a Josh Olson film looks like, but I know what a Cronenberg film is and this is definitely one of those.

ReplyDeleteGranted, I'm coming from a perspective where a film is written, cast, directed, produced, and edited by a single person under ideal circumstances.

Jeff,

ReplyDeleteI see what you're saying about auteur theory providing a map that lets you see what you should be looking for in a particular film—but it seems to me like it depends on a director having a body of work behind him that you can use to figure out what you should be looking for. Josh Olson has six scripts in various stages of development hell and one direct-to-video movie—but the ones that were originally his are revenge/action-type stories; give it a few years and you might know what a Josh Olson film looks like.

Put it like this—I don't deny that there are common threads in all of Cronenberg's movies, and that the director's role, once production starts, is a unique sort of managerial/orchestrator thing that does act as a filter. But I don't think that equals authorship. Or if you have to assign an author for some movies, I don't think it has to be the director who gets it. I know what a Charlie Kaufman movie looks like no matter who directs it (well, "looks like" isn't quite the right term). You could probably make a similar case for Walter Murch or Gordon Willis. Or Cary Granat at Walden for that matter.

I guess I don't really see the point of assigning a single author to a collaborative medium like film except as critical shorthand; it's useful to be able to talk about a movie as if it had a single creator, and I do it all over this website. And it's very useful if you're a director or a director's agent and you want to ask for more money; once auteur theory came along it was sure to be promoted by directors forever and ever. But outside of those reasons, why does a film need an author at all? It seems to me that it doesn't give you too much benefit from an interpretive standpoint (in fact, I think it makes you more likely to attribute meaning or intent where there is none), and it costs you a lot of insight into the influence other people have on the process.

I'm not sure that the ideal situation is putting one person in charge of the whole production either, but more on that later. For now I'm curious whether you think anyone but a director can be an auteur.

Of course, obviously Charlie Kaufman but also, among screenwriters, Paul Schrader and Paddy Chayefsky; among producers, Jerry Bruckheimer or Joel Silver; among actors, Tom Cruise or John Wayne; and among cinematographers, Janusz Kaminski or John Toll. Although the more specialized the skill, the less the person has to do with the overall film. I read an article once by Jonathan Rosenbaum where he claimed that Taxi Driver was the product of four auteurs: Scorsese, Schrader, DeNiro, and Bernard Herrmann.

ReplyDeleteI don't think auteur theory means that one person is defined as the definitive sole creator of a film. That would, indeed, be foolish and silly. But it is a useful tool in particular circumstances, just as feminist theory or other theories are, depending on the circumstance. But to deny it seems to cost you a deeper level of insight into a film; most of my favorite films I would say were driven by sole auteurs (Kubrick, Hitchcock) and to watch them is, for me, to see every aspect of the filmmaking process bent towards a single, unified vision.

We should hang out sometime and try to catch something.

If any artist who puts a distinctive mark on a film can qualify as an auteur, then we're basically on the same page. I haven't read Truffaut or Sarris so my understanding of the theory is relatively superficial but I thought that only directors qualified, at least in the original formulation. Camera as pen and all that. The Rosenbaum article sounds interesting; do you have a copy?

ReplyDeleteWe should hang out and catch a movie sometime soon for sure. Anything interesting opening soon? I noticed to my surprise that the Arclight is having a midnight showing of The Lake House this Thursday, for people who just can't wait to see it on Friday afternoon... I'll email you.

I think the Rosenbaum article is in one of his books, and if so, you can borrow if from me.

ReplyDeleteI think the 'directors only' thing probably was how Truffaut etc. did initially conceive of it. But that was back in the 1950s, when people still thought carbs were good for you and didn't have Ipods.

Hey Matt,

ReplyDeleteYou mention the genre-jumping nature of The 39 Steps, The Lady Vanishes, Black Narcissus and I Know Where I'm Going - do you think this is a function of the time and place they were made and/or the particular directors who made them (Hitchcock in Britain in the mid to late 30s, P&P in Britain in the mid to late 40s)? Or is that just a fallacy built on the curatorial decisions of the Criterion Collection?

I’m going to make a confession: as much as I love movies, I have a hard time with most made before about 1937-1938. After that I find the technology of cinema fairly seamless and unobtrusive. And while there are some exceptions (The General, City Lights, M come immediately to mind), earlier than that the ricketiness of the technology often gets in the way for me. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t much care for The Lady Vanishes. So I wasn’t expecting to like The 39 Steps. But I do. I like it a lot.

ReplyDeleteThere are many similarities with North by Northwest, a film I’d never seen which aired on TCM last week while I was in the midst of all things 39 Steps. Another confession: despite being made a generation later and with vastly improved financial and technical resources, North by Northwest was a surprising disappointment. Blasphemy, I know, North by Northwest being one of the high marks of the canon and all. The similarities in theme didn’t bother me, but there are virtually identical shots and scenes between the two films. I felt let-down that Hitchcock hadn’t learned anything new between 1935 and 1959. And the “wronged man on the run” plot is not well served by the inflated budget and overall polish of the Hollywood production. The single instance in which the extra money was well spent is the justifiably famous crop duster scene, a huge improvement over an inexplicably speeded up Keystone Cops type chase across the moors of Scotland in The 39 Steps that includes that silly stock shot of a helicopter that is completely inconsequential to the scene. Was there ever a time when that shot seemed spectacular?

Lucie Mannheim, Peggy Ashcroft, Madeleine Carroll…the women steal this show. After my first viewing I’d given Peggy Ashcroft the gold, but by my third go-through I was enamored of Madeleine Carroll, particularly in a scene I hadn’t much noticed the first two times around. She’s handcuffed and in bed with Robert Donat (sounds salacious but it isn’t). He’s laying down in the foreground, she’s behind him sitting up against the headboard. He’s spinning harmless lies about his criminal past, she’s listening. Although he’s got ninety percent of the scene’s dialogue, only Carroll is in focus. It’s not about what he’s saying, it’s about her reactions to what he’s saying. It’s her subtle, natural, and charming performance here that makes this my favorite scene in the film.