Yojimbo, 1961, directed by Akira Kurosawa, written by Ryuzo Kikushima and Akira Kurosawa.

I've always had a sentimental affection for antiheroes, from Nic Cage's Yuri Orlov straight back to Milton's Satan. It's no surprise, then, that I enjoyed Yojimbo, Akira Kurosawa's skillful fusion of archetypes from gangster movies and Westerns. Toshirô Mifune plays Sanjuro, a samurai with no master, and from the first shot, you know he's going to be something of a Byronic hero.

Kurosawa follows him with the camera from behind all through the credits. He towers over the mountains! To gaze upon his face is to gaze into the abyss! And so on. By the time he turns around, he's gotten the heroic stature he'll keep throughout the film. Which is not to say he's a conventional hero. At the film's opening, he more or less randomly wanders into a town with, shall we say, something of a violence problem. Townspeople watch him walk down the main street from behind windows, but no one's outside. No one, that is, except for the happiest dog in the world, bounding down the street:

Yes, that's a human hand. And yes, David Lynch stole this for Wild at Heart. The great thing about the dog eating the hand is this: it's a joke. One person jokes about it briefly afterwards, but that's it. As far as I could tell, you never see whoever had their hand cut off. It seems Tarantino didn't completely invent referenceless violence.

In the samurai movies I've seen so far, where there's a town in trouble, bandits can't be far behind. Yojimbo is different; the town is tearing itself apart. There are two warring groups of criminals, and nearly everyone is associated with one or the other (the two exceptions are a man who runs a restaurant of sorts, and the coffin-maker). Rather than trying to save anyone from anything, Sanjuro sticks around because, as he puts it, "In this town, I'll get paid for killing. And this town is full of men who'd be better off dead." Then he gleefully plays both sides against each other for his own profit. You can see visually what he's up to here:

That's Sanjuro at the top of the tower, watching both sides preparing to kill each other (they don't--they're interrupted). And you can see how he feels about the prospect of observing this kind of slaughter in closeup:

He could be watching the best circus in the world. As you can see, he's not a hero in the Shane mold, the kind who's slow to rile, but uses violence when absolutely necessary. This is a man who introduces himself to the townspeople by killing three men for no good reason; he resorts to violence early and often, and he takes genuine pleasure in it.

Things go according to his plans for the first half of the movie (which is to say, both factions gear up to annihilate each other and offer him increasing amounts of money to side with them), until the unexpected arrival of Unosuke, a more valuable fighter than Yojimbo. See if you can figure out why he's such a terror on the battlefield:

I'm not sure why Unosuke has a sword as well as a revolver, but as you can see, Sanjuro's swords are outclassed. Is Unosuke an honorable fighter, there to remind Sanjuro of the ideals he betrayed by becoming a mercenary?

Not so much, it turns out. Unosuke complicates the balance of power, but he doesn't add any moral complexity. The rest of the movie more or less follows traditional stereotypes of the Western: Sanjuro, against his better judgement, helps out a poor family; this act of kindness leads to his capture and torture, until he escapes and takes on his enemies in a showdown in the town's main street. The difference here is that by the time Sanjuro defeats his enemies, everything of value in the town has been destroyed, and the population is down to three citizens, all old men (Sanjuro surveys the situation and says, "Now it'll be quiet in this town"). It works as a Western or a black comedy—take your pick. As Bowsley Crothers pointed out at the time (calling it a "forthright travesty"), the only thing it's not is a samurai movie; there's nothing Japanese about it except the cast and crew.

Yojimbo may be predictable, but a movie built around a Byronic hero like Sanjuro doesn't need to have a fresh plot to succeed. It just needs to make sure that its antihero is fun to watch. Toshirô Mifune's performance is truly exceptional, and saves the movie. He has a kind of lazy cool about him that owes more to gangster movies than Westerns. Check out his expression below: the man closest to him has just said, "Kill me, if you can!"

Mifune chews on his toothpick, looks at him with the "are you sure?" expression you see in the still, and deadpans, "It'll hurt..." The man draws his sword, Sanjuro shrugs his shoulders, remarks, "No cure for fools." Then he kills the man and two of his friends. And a new screenwriting cliché was born, the "action-hero-wisecrack-before-slaughtering-enemies" so beloved of the Die Hard movies. I suppose it's unfair to blame Kurosawa for John McClane (though it would make a great dissertation). Mifune's performance is such swaggering fun you can forgive Yojimbo its excesses, its cartoonish characters, its unlikely plot turns. The pleasures this film has to offer are all on the surface; no one will ever call it insightful or penetrating. But if you're willing to spend a few hours coasting on the surface of things, you could do worse than watching Toshirô Mifune destroy a town for fun and profit.

Randoms:

- Donald Ritchie believes this is the best photographed of all of Kurosawa's films. There are a lot of striking compositions, most having to do with objects in both foreground and background. Here's a shot that struck me: the head of one of the warring factions, his wife, and their son are arguing. Look how claustrophobic he makes the normally expansive 2.35:1 frame here.

- The cinematography is by Kazuo Miyagawa, who also shot Rashomon.

- While we're on the subject of Miyagawa, his C.V. includes a movie called Zatôichi to Yôjinbô (Zatôichi Meets Yojimbo), which would appear to be in the tradition of the Godzilla movies (or the Abbott and Costello ones, for that matter), pairing heroes from past films. Toshirô Mifune apparently reprises his role from the original Yojimbo, although this time his character is named "Sassa" instead of Sanjuro. Zatôichi, by the way, was a blind swordsman played by Shintarô Katsu in at least 25 films and a television series. It sounds pretty shameless—has anyone seen it?

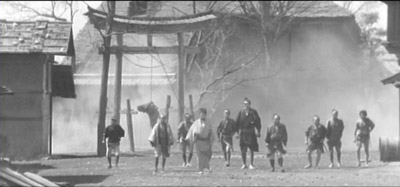

- It's not unusual for a trailer to have footage that doesn't end up in the final film; trailers are usually cut before the film is locked. But the trailer for Yojimbo seems to have footage from a complete alternate version of the final scene. In the finished film, Sanjuro faces off against all the surviving bad guys, who approach him in a large group:

- But in the trailer, the same footage of Toshirô Mifune is paired with shots of Tatsuya Nakadai approaching alone, like this:

- This makes it appear that the final standoff is a one-on-one contest between Sanjuro and Unosuke. And the trailer ends with this Great Train Robbery shot, which I also don't remember being in the final film:

- It looks like Kurosawa shot an alternate version of the final fight—and I can only imagine he did it exclusively for the trailer, since it wouldn't make sense to have Unosuke alone in this scene.

- Yojimbo has pretty culturally varied ancestors and progeny. Kurosawa was supposedly inspired by Red Harvest, a Dashiell Hammet novel in which the Sanjuro character is a detective playing gangs off each other. Kurosawa set it in Japan, Sergio Leone set it in the west (as A Fistfull of Dollars) and Walter Hill set it back in gangland territory for New Line Cinema's Last Man Standing. Apparently there's something about setting up evil people to kill each other that transcends cultural differences.

3 Kurasawa (Kurasawii?) down, 11 to go. I like his films, but seems a bit much.

ReplyDeleteI just looked at the list, and Bergman wins with a total of 16. I barely made it through 2 Bergmans. I could never do it. Do you think Criterion makes a point of giving a couple of directors so many slots?

Yan, I think it's a combination of two things. One is that Criterion has a close relationship with Janus Films, which still controls American distribution rights for an incredible percentage of foreign films of the fifties and sixties (I think they were about the only company buying these rights from 1955 to around 1965, when other studios started to get interested). So Kurosawa and Bergman movies are easy for Criterion to get rights to, unlike, say, Hitchcock movies. The other thing, I guess, is that someone at Criterion loves both directors. Bergman, by the way, baffles me also, but all I've seen so far is The Seventh Seal. Have you ever looked through Criterion's old laserdisc catalog? Because laserdiscs were such a specialty market, American studios gave Criterion the rights to a lot more movies--there's still a lot of Bergman and Kurosawa but I think it's an interesting list as it seems to be what they would release if rights were no object. Some of the movies are pretty surprising: Ghostbusters, From Russia With Love, and, of all things, Evita!

ReplyDeleteZatoichi Meets Yojimbo is ok, and as a avid Zatoichi fan I must admit I enjoyed this depature from the fairly formulalic series. It's a much better than the equally hoaky team up between Zatoichi and the One Armed Swordsman. (a famous Shaw Brothers character)

ReplyDeleteThe Don,

ReplyDeleteI'll check it out, then. Is there a Zatôichi film you'd recommend starting with if I wanted to see some of that series first?

Take a look at a Janus films videotape release of a Kurosawa film, or try to see one of their prints screened sometime. The original subtitles are very interesting. For instance, in Yojimbo, when Mifune is confronting those three guys, one of them says, in the subtitles: "Don't mess with us! We're dangerous men! I've got the death penalty in three districts!"

ReplyDeleteThen Mifune whips his sword out and cuts one of their arms off.

The Criterion discs have been largely re-subtitled, but those original subtitles are what would of been on the films if you'd seen them in say, the late-60s to the late-70s--if you were watching them while writing a Kurosawa influenced epic space opera, for instance.

JJ,

ReplyDeleteI didn't know that -- that's fascinating. I thought he'd stolen everything from The Hidden Fortress, (which I haven't yet seen), but I guess all Kurosawa was fair game, huh?

I personally think the Zatoichi films are absolutely fantastic!

ReplyDeleteBest to start with #3, the first in color (although 1 and 2 are sort of important, plot-wise to what comes after...)

Katsu Shintaro is magnificent throughout the series -- and there is something about the location photography that makes me very nostalgic -- for something?

The Yojimbo-Zatoichi entry is good, but not one of the best.

BTW, Kitano's recent Zatoichi is truly excellent, as well.

Lewis Saul

www.lewissaul.blogspot.com

Lewis,

ReplyDeleteWell, you know me, I'm a stickler for watching things in order; I imagine I'll start with the first one.

Hi, Matt -- congrats on getting "discovered" -- you are seriously awesome..

ReplyDeleteI just finished up a post on Yojimbo for a friend of mine's poetry blog:

http://thebestamericanpoetry.typepad.com/the_best_american_poetry/2010/02/xxvi-the-30-films-of-akira-kurosawa-yojimbo-1961-by-lewis-saul.html

I would very much like to use TWO and only TWO captures of yours -- the hand in the dog's mouth and the fire raging above Onusuke's head.

If you have a problem, I understand and that's fine -- you did a lot of work to capture all those images. I wish I had the equipment at this point, but I don't.

Let me know, please ... I'd appreciate it very much.

Lewis Saul

I've been reading your reviews this afternoon with pleasure. I live in Osaka, so I've got a bit of a fixation with those Japanese directors from the 50s 60s.

ReplyDeleteIn Yojimbo, the character Unosuke has a gun but still wears a sword simply because he's a samurai. The sword was a sign of his rank in society- even a scrawny little bureaucrat samurai had to wear one, even if he never actually used it. In theory, the samurai were the national militia and were on call at all times.

Also, did you notice good old Eijiro Tono as the world-weary tavern-keeper? Brilliant as usual – no wonder Ozu and Kurosawa loved him.

Colin,

ReplyDeleteThat's interesting -- I didn't realize they had to wear the swords.

I'm getting started on my new screenplay, "Scrawny Little Bureaucrat Samurai," as soon as I post this.

Matt

Yes, the sword is a symbol of status, but I look at it more as the criminals wear swords because samurai do -- NOT because they tehmselves are samurai.

ReplyDeleteMy take on Sanjuro is a little different. He's not destroying the town, he's saving it. Saving it for the poor folk, even though he despises that they won't stand up for themselves.

And the guy with the jitte? He's the 'town official'. Who the criminals mostly leave alone because it's bad juju to off the local official -- expecisally if you've already bought him.

The Zatoichi stuff is interesting, and also NOT samurai. Zatoichi spends his time nearly exclusively in the underclass, while not seeming to be touched by it.

The dog-hand is certainly not just a joke. It is a zen reference to Huike, the first disciple of Bodhidharma, who cut off his hand in order to attain enlightenment. Toshio is searching in the scene, searching for some sign to guide him about the desolate town he has found himself thrown into. In very many ways this search is a prolonged one which is evident throughout the movie. Toshio is searching, while walking the middle path between the two factions, very similar to Huike in his own search for enlightenment, walking down the Buddhist middle path.

ReplyDeleteThe Zatôichi film is, as you call it, shameless. It plays off superficial aspects of both Katsu's and Mifune's characters, in a rather mindless plot exercise. To their credit, not all the Zatôichi films are such cheap fare. The one's directed by Kenji Misumi were significantly better; from what I've been given to understand, he had a lot of influence on subject, development, and composition. I've seen Zatôichi and the Chess Expert twice, and enjoyed it on both occasions. The "surprises" aren't even surprising the first time through, but then, the Japanese evidently like to know such things in advance, and enjoy watching how well such things are done, instead.

ReplyDeleteHey, now you get to watch Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (and every other Zatoichi movie, with Katsu at least)!

ReplyDelete